Andrew Paul Wood – 7 May, 2020

Whereas Volume One took us through McCahon's early development, the figurative landscapes and religious painting, and the Titirangi cubo-impressionist kauri, Volume Two touches us down following the US sojourn when the artist clicked with American abstraction and saw something in Mondrian that no one else did.

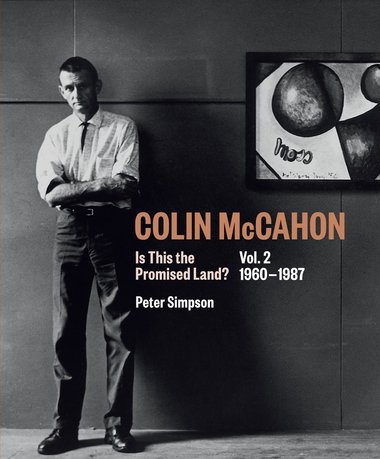

Peter Simpson

Colin McCahon: Is This the Promised Land? Vol. 2 1960-1987

400 pp, coloured illustrationsAuckland University Press, April 2020

Tentative date for launch: 11 June.

ISBN: 9781869409081

RRP: $79.99

The second, much anticipated volume of Peter Simpson’s two volume study of Aotearoa’s most important twentieth century artist is all that could be hoped for and then some. As with Volume One, Colin McCahon: There is Only One Direction, which covered the years 1919 to 1959, we are presented with a meticulously researched and annotated, sumptuously illustrated book (something of a miracle in itself, given how notoriously difficult the McCahon Trust can be to deal with) and we are here for it. Oh, it’s lovely!

Whereas Volume One took us through McCahon’s early development, the figurative landscapes and religious painting, and the Titirangi cubo-impressionist kauri, Volume Two touches us down following the US sojourn when the artist clicked with American abstraction and saw something in Mondrian that no one else did. I call it full-blown symbolism in the sense of the late-nineteenth century art movement with its rejection of naturalism and realism, and its embrace of spirituality and oblique references to transcendental truths. The English word symbol comes from two Latin words—symbolum, a symbol of faith, and symbolus, a sign of acknowledgement—both of which seem eminently suitable to apply to McCahon’s painting.

With reference to McCahon‘s own letters, Simpson does an excellent job of teasing out the thought process behind the artist’s idiosyncratic take on Mondrian and it is probably no coincidence that this segues into the Bellini Madonna paintings of 1961-62, given that the original Bellini paintings and McCahon’s Here I give thanks to Mondrian (1961) are all ex-votos or devotional images of a sort.

Rather than presented as disjointed and discrete phases, Simpson reveals in broad arcs the interconnectedness of the waterfalls, the Gates paintings, the 1966 Stations of the Cross, and Victory over Death 2 (1970)—the latter presented to Australia by Robert Muldoon as a kind of back-handed gift, but one which cemented Australia’s respect for McCahon—and the deeply moving Necessary Protection Muriwai works of 1971.

One can’t help but suspect, however, that many of the seemingly random black diagonals that appear in the landscapes of this period own more to the windscreen wiper of the Morris he sat and painted the view through the windscreen in than anything too deep about wanting to break the square or disrupt the illusion of space à la Mondrian’s neoplasticism.

As for anyone who dares suggest McCahon wasn’t much of a colourist, Simpson devotes respectable space to the Rosegarden paintings and Urewera posters the artist made in Muriwai in the mid-1970s. They are the sort of McCahons that never do well at auction because they don’t look like the popular perception of what a McCahon should look like, but they exude life with their oranges, pinks and yellows.

As a former English Professor, Simpson is wonderfully attuned to the subtleties of McCahon‘s painted words, analysing the works as texts on two levels, guiding the reader through contextual analysis, the hidden meanings and biographical references, and the symbolic vocabulary that often proves far more concrete or spiritually literal and less abstract than they first appear. Caravaggio is said to have retrenched from painting angels later in his career because he had never seen one. McCahon, more mystic than straight Christian, like William Blake before him, could see through the eyes of spiritual yearning, and rendered them as orderly white rectangles on the darkness of the pictorial plane.

A forest of Tau crosses flourishes as McCahon’s health declines and he wrestles with his own mortality. The painting deteriorates and eventually dries up. By the early 1980s Korsakov’s syndrome (dementia brought on by the artist’s alcoholism) had McCahon in its grip and it’s a tragic irony that after decades of public hostility he was in no state to appreciate such acknowledgements as I Will Need Words, the exhibition of his work (curated by Wystan Curnow) included in the 1984 Sydney Biennale.

It is redundant of me to repeat that story when Simpson does a far better job of it, concluding with an overview of McCahon‘s afterlife as New Zealand’s most internationally appreciated artist since Frances Hodgkins. Simpson is a sensitive, thorough, informed and informative guide to this monolithic figure whose shadow, even now, New Zealand artists struggle to entirely escape from. This is an exceptional book. Get both volumes: they are an indispensable resource and the most comprehensive guide to McCahon you will ever need.

Andrew Paul Wood

Recent Comments

Andrew Paul Wood

I offer an amendment, the Trust is a much more efficient and generous beast these days, I am informed. I ...

John Hurrell

Andrew, this book is such an exciting project--to cover the creative endeavours within the last 27 years of McCahon's life. ...

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects Advertising in this column

Advertising in this column

This Discussion has 2 comments.

Comment

John Hurrell, 10:19 a.m. 10 May, 2020 #

Andrew, this book is such an exciting project--to cover the creative endeavours within the last 27 years of McCahon's life. I'm keen to see what Peter has to say about the big black Biblical text paintings, and the extraordinary number ones too.

Andrew Paul Wood, 9:47 a.m. 2 June, 2020 #

I offer an amendment, the Trust is a much more efficient and generous beast these days, I am informed. I offer my apologies.

Participate

Register to Participate.

Sign in

Sign in to an existing account.