John Hurrell – 15 September, 2022

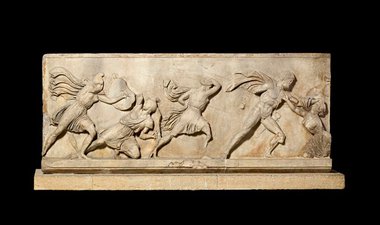

One real treat is a marble carving of a battle scene in a section of frieze (350 BCE) from the huge shrine of King Mausolus. It shows armoured soldiers fighting ferocious female warriors (Amazons) hurling themselves into battle.

Auckland

Items selected from the British Museum Collection

Ancient Greeks: Athletes, Warriors and Heroes

11 June - 6 November 2022

This beautifully presented touring show brings to Auckland over 170 items from the Collection of the British Museum, giving us the chance to admire them and to look at the enormous impact of Greek culture on multiple creative fields—that range from art, mathematics and philosophy to sport, drama and poetry—and (if you are so inclined) to think about its own pollination through trade from other ancient cultures such as India.

Greek sexuality and ethics have been much examined by philosophers as diverse as Michel Foucault and Bernard Williams, and as I’ve hinted above, the notion of Greece being in isolation the ‘cradle of western civilization’ is now disputed by scholars like performance expert the late Thomas McEvilley—despite its enormous influence on Roman culture—with ancient Egypt also seen now to be influencing it.

Plus if you have a copy of The Iliad at home, and it is translated by somebody as skilled as for example Robert Fagles, then Homer’s battle scenes, in conjunction with say the vase paintings, become as gruesomely vivid as any war movie by Spielberg.

Unfortunately much of ancient Greek culture has been lost, such as the wall and panel paintings of the 5-6 BCE, and poetry of writers like Sappho of which only a few fragments remain. Or scientific papyrus scrolls in the great library of Alexandria which then declined after 145 BCE, and was not suddenly destroyed by fire as is commonly believed.

The period of time covered in the show extends from the Geometric Period (900-700 BCE) up to the conquering Romans (27 BCE-400 CE) when Octavius (Augustus) ruled. Greece was not united but consisted of 1,500 independent city-states, often scrapping amongst themselves, and cities forming alliances. The major, most prolonged, conflicts consisted of the Persian Wars (490-479 BCE), the Peloponnesian War (431-404 BCE) and the Macedonian Conquest (360-323 BCE).

It is a carefully organised informative exhibition that uses dramatically lit unpainted statues, red or black figured (painted) pots, coins, gold and silver jewellery, bronze tools, weapons and armour, terracotta toys, marble busts and friezes, oil containers, wine jugs and more to methodically elucidate a suite of five themes on Grecian life and values. They are: competition (sport and recreational domestic games like knucklebones, marbles and dice) in the ancient world; performing arts (theatre, music, poetry and dance); its societal view of life and death; war the ultimate contest (looking at armoured hoplite foot soldiers and cavalry); heroes and myths, human interaction with the Gods of Mt Olympus.

These thematic groupings are used—through the varied juxtaposed artefacts and informative labels—to make the preoccupations of daily life two and a half thousand years ago, effectively vivid for the visitor: showing us details. Often the themed sections overlap, such as when training athletes are also training to acquire fighting skills such as body flexibility or quick movement.

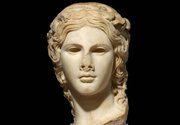

One of my favourite works is a statue (150-100 BCE) of an elegant, well dressed, noblewoman with a serene face and poised gesture. It is made of Parian marble and originally would have been painted. She is wearing two layers, one that is sheer over a heavier woollen garment. She has a slightly aloof ambience and is also covering her hands as a sign of modesty.

There is also a somewhat worn statue (300-200 BCE) of winged Nike, the goddess of sporting victory, who is like a suddenly materialising angel. She looks otherworldly but nevertheless is busy and active in her searching out and rewarding of champions.

A large pot, a neck amphora (470-460 BCE) that sometimes contains olive oil as a prize, depicts a red-figured winged Nike fluttering in mid-air and offering a victor’s ribbon to a sporting winner, for him to proudly wrap around and wear. The athlete is depicted on the other side of the jar.

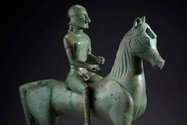

One sweet surprise is a small running bronze athlete (480 BCE), naked and skinny but with a confident, cheeky expression on his face. He is like a little mischievous stick figure. In contrast, a bronze cavalryman on a horse (560-550 BCE) is larger and much more solid, but slightly stilted; more a stereotype than a living spontaneous individual.

There is also a bronze Corinthian helmet (550-500 BCE) with an inverted peak to protect the nose and smooth curved back to cover the neck. The lack of earholes to enable listening for commands or sneaky enemies was a disadvantage.

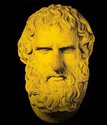

A marble bust of Dionysus (120-140 CE but copied from a Greek original 150-100 BCE), the god of revelry, intoxication and fertility, has penetrating hollow eyes that add to its expressiveness. Originally it had glass eyes, with bronze eyelashes, and was painted. Even with the paint gone and a chipped off nose it is elegant, being slightly androgenous with a sultry air.

One real treat is a marble carving of a battle scene in a section of frieze (350 BCE) from the huge shrine of King Mausolus. It shows armoured soldiers fighting ferocious female warriors (Amazons) hurling themselves into battle.

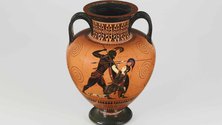

Also standing out is a black-figured vase (520 BCE), showing a racing charioteer with a team of furiously galloping horses, that coincidentally has their flailing legs looking similar to Balla’s famous 1912 painting of a running dog on a leash—even though the effect is caused by four horses with four individually painted legs each, fixed in a slice of time—and not strictly a study of motion.

I’m very partial to the wine jugs (chous) too, especially one (420-400 BCE) showing a small boy playing a lyre, accompanied by a yapping dog and strutting bird. These containers have no vertical handle but a narrow neck with four outward-facing, undulating, spouts at the top rim. Related are the thin oil flasks (lekythos) for holding the liquid wrestlers and other athletes used to coat their muscular bodies. After competing they would use curved tools to scrape it off.

Sometimes the oil was perfumed and used specifically for funerary rituals. The painting on one white ground example (420-400 BCE) is very different from the ubiquitous red or black figured painting on other containers, in that here positive and negative shapes are not accentuated. The unfired paintwork was more fragile and delicate, emphasising more aspects of linear drawing, and not using colour to block out forms.

This exciting exhibition allows you to visually sort through a large assortment of functional and contemplative objects and ponder a selection, while keeping in mind aspects of what they meant to their owners within their relevant historic contexts—and what they might mean to us in our own.

And if this presentation turns out to be a bit of a revelation, there is also a great black-figured battle scene on a pot from the Auckland Museum’s own collection—and other Grecian delights—on show in Ancient Worlds on Level One. An abundence of riches!

John Hurrell

Advertising in this column

Advertising in this column Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

This Discussion has 0 comments.

Comment

Participate

Register to Participate.

Sign in

Sign in to an existing account.