John Hurrell – 19 September, 2023

Of the six categories, my favourites are the last two, the Trade & Influence and Resistance and Colonialisation ones. The first wrestles with the notion of an indigeneity that is constant and pure, free of impact from ‘foreign' forces that may have penetrated its borders. The second examines the retreating impact of colonialism, its harmful consequences challenged by fierce counter-movements with eloquently structured arguments and sometimes innovative and fresh materials.

Auckland

Works from over 160 indigenous artists from the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Collections of the National Gallery of Australia (in Canberra) and the Wesfarmers Collection (based in Perth)

Ever Present: First Peoples Art of Australia

Curated by Tina Baum

29 July - 29 October 2023

On 14 October, the same day as our election day, the people of Australia will also have an important time of decision, for they will have The Voice, a referendum proposing far greater participatory rights for aboriginal communities and ensuring their constitutional status within the greater Australian population. At this current moment, shockingly, opinion polls indicate the overall Aussie population is opposed to any change.

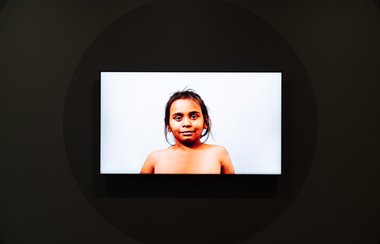

Reading about this very important coming event reminded me of two brilliant video works that I recently saw in the exhibition, Ever Present, a new survey exhibition of indigenous Australian art at AAG.

One was, At Face Value, by Raymond Zada, of assorted indigenous faces continuously morphing into each other in a flowing stream of malleable heads, and the other was Forced into Images, a work by Destiny Deacon and Virginia Fraser. They both examine the stereotypical facial templates of ethnicity, challenging conventional expectations of racial physiognomies, the Deacon/Fraser work featuring two children clowning around with ‘aboriginal’ masks.

Ever Present is the first show of indigenous Australian art to come here since the My Country presentation of 2014, and wonderfully is more sprawling in scale, time bracket, and included varieties of media—that range from iridescent shell jewellery and eel traps to fiercely political video installations.

A touring exhibition, it is sufficiently complicated in its varied selection of over a 170 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander works to require several visits. The exhibits though, are skilfully structured into six interlocking and overlapping categories: Ancestors & Creators; Country & Constellations; Community & Family; Culture & Ceremony; Trade & Influence; Resistance & Colonisation. Sometimes these brackets jump around. The selector is Tina Baum, the curator in this subject at the National Gallery of Australia, in Canberra.

In this exhibition, which points out the spectacular age of these artistic and oral traditions, and which hints at the notion of time standing still—believing that familial predecessors are always around in spirit and animal form—a lot of the paintings are disarmingly beautiful, though also functionally preoccupied with story-telling (rather than formalist abstraction). Nevertheless, even before you ponder local cultural reference points (such as ‘dreamed’ communications from ancestors, oral rituals and myths, totemic animal clans, clear starry skies for navigation and aerial [or cross-sectioned] landscapes) and modes of interpretation from legends or local narratives, their matte surface qualities and ochre patterned motifs range from an appealingly delicate intricacy to a compositionally bold and stridently raw (and literal) earthiness.

These striking works are overtly embedded in the international contemporary art market (especially since the early 1980s), as well as First People’s culture, languages and traditions. Therefore for the gallery visitor, the exceptionally lucid wall labels are crucial for grasping the narrative nature of the imagery, particularly the motivations of the artists and their communities.

With the six varieties, the first two in the sequence are closest to pre-European Australian painting (not performance artefacts) in the style, feeling and motifs that initially were earth pigments painted onto hollow trees, rockfaces, tribal bodies or sandy ground. Even though ancestral myths and animal imagery are their driving content, they are at times unnervingly like contemporary North American abstraction.

Emily Kam Kngwarry’s large horizontal painting, Yam Awely, for example, could be mistaken for a very busy Brice Marden with its entangled flowing lines that represent generating yam tubers. (He in fact now collects such paintings for his home.) Other works, like Ivan Namirrkki’s abstract Hunting Crocodiles by Moonlight Under the Milky Way, though painted on undulating eucalyptus bark, are tightly structured in a precise grid and very finely made, referencing the reptile’s hide textures when seen beneath the moon. A few are less structured and more holistic, such as Gulumbu Yunupingo’s painted, termite-eaten, hollow log, Gan’yu (Stars), where no straight edges are to be found.

A few paintings, like Danie Mellor’s The Song Cycle, or Brook Andrew’s Australia 1—even if hand-painted over projected slides—have a shimmering screened photographic ambience like that of Polke or Warhol, with a clearly twentieth century technological sensibility.

Of the six categories, my favourites are the last two, the Trade & Influence and Resistance and Colonialisation ones.

The first wrestles with the notion of an indigeneity that is constant and pure, free of impact from ‘foreign’ forces that may have penetrated its borders. Examples are Jock Puautjimi’s tutini (ceremonial glass poles made with Netherlands’ collaborator Luna Ryan), Yilpi Marks’ Untitled (a batik clearly showing an Indonesian influence) and John Mawurndjul AM, Rainbow Serpent (with Buffalo)—the presence of recently introduced land animals.

The second examines the retreating impact of colonialism, its harmful consequences challenged by fierce counter-movements with eloquently structured arguments and sometimes innovative and fresh materials. Excellent examples here are Judy Watson, Names of Places (a videoed listing of sites of massacre); Christian Thompson, Berceuse (another video featuring a lullaby sung in an extinct language); Yhonnie Scarce, Silence Part 1 & 2 (glass ‘Indigenous organs’ tortured by stainless steel European forceps during medical experiments); Damien Shen & Richard Lyons, Ventral Aspect of a Male to One Side #1 (a photographic satire of dehumanising anthropological documentation).

This varied, thematically rich, carefully woven exhibition is well worth several visits. Extremely sensual and yet packed with harsh political issues about colonial history, it is impossible to encounter and then glibly leave unaffected.

John Hurrell

Advertising in this column

Advertising in this column Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

This Discussion has 0 comments.

Comment

Participate

Register to Participate.

Sign in

Sign in to an existing account.