John Hurrell – 14 April, 2014

One of the most dominant themes is that of art aimed at pressuring white Australians to come to terms with the horrendously brutal (sometimes genocidal) consequences of Australian colonialism. There is more involved here than just circulating damning historical information, or even the cathartic benefits of justified anger. There is a seeking of signs of genuine remorse on the part of the descendants of the early European settlers - via the government.

Auckland

Aboriginal art from QAG/GOMA

My Country: Contemporary Art from Black Australia

Curated by Bruce McLean

28 March - 20 July 2014

This exhibition of contemporary (and arguably traditional) Aboriginal and Torres Strait Island art is a reduced version of QAG/GOMA’s My Country, I Still Call Australia Home: Contemporary Art from Black Australia which was presented in Brisbane last June, and initiated here by the ex Auckland Art Gallery director /new Queensland Art Gallery director, Chris Saines. After being culled from a larger, more sprawling, presentation that was curated by Bruce McLean (associated with the Wirri/Birri-Gubba community in Queensland), forty-six artists from many different parts of Australia now present in Auckland nearly a hundred works, ranging from video to painting. A few are not even immediately identifiable as Australian: it is not all overt geographical branding and the themes are refreshingly varied.

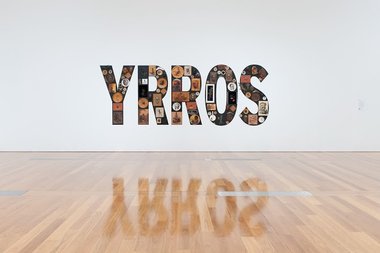

One of the most dominant themes is that of art aimed at pressuring white Australians to come to terms with the horrendously brutal (sometimes genocidal) consequences of Australian colonialism. There is more involved here than just circulating damning historical information, or even the cathartic benefits of justified anger. There is a seeking of signs of genuine remorse on the part of the descendants of the early European settlers - via the government. Some of the work - particularly that of Richard Bell, Tony Albert and Bindi Cole - is about expectations of contrition, and anger when official apologies for despicable actions have not appeared to be sincere, or have been contradicted by subsequent events. One work in particular, Seventy Times Seven, a video by Bindi Cole, is very witty, referencing the bible and having 490 aboriginal people say ‘I forgive you’, that number apparently being Christ’s stipulated limit for maintaining tolerance.

Another brilliantly sly work is by Dianne Jones, who takes John Webber’s 1782 portrait of James Cook and adds a rakish moustache and a wispy goatee, making him a thieving scoundrel - not a ‘discoverer’ of an ‘uninhabited’ continent. She has used a reference to Duchamp’s obscene phonetic joke about the Mona Lisa to turn Cook into a villainous conniving pirate.

Other contributions, focussed on righteous fury (Fiona Foley, Gordon Hookey, Warwick Thornton), avoid such nuance, being deliberately heavy-handed, an outpouring of understandable Aboriginal rage or grief that’s possibly counterproductive. For example, Gordon Hookey offers a punchbag on which are painted images of John Howard, Pauline Hanson and other rightwing politicians - with piggish features. A set of boxing gloves, painted in the colours of the Indigenous Australian flag, is placed on the ground nearby. Or, as in the case of Warwick Thornton, the artist cornily presents himself as a martyr on a revolving lightbox cross - without irony.

As expected in a show like this, there are plenty of gorgeous ochre coloured paintings and log sculptures. What is surprising though is the quality of the videos and photographs. One example is Matinee, a fantastic video by Destiny Deacon and Virginia Fraser of a black man and white woman soundlessly waltzing in a strange room that they enter via a high iron gate. The slow moving, grainy image has a mysterious lyricism and wonderful optimism when the blurry figures swirl around the hermetic space.

Genevieve Grieves presents videos of five nineteenth century studio photographs being set up with posed groups of Indigenous Australians, filming for several minutes before and after each formal sepia shot - in order to capture the mingling, ordering, and disintegration of the staged group dynamic. The restless shuffling bodies, compositional try-outs and general horseplay make this work an intriguing contribution. It alludes to narratives behind the frozen image.

Christian Thompson’s large coloured photographic self portraits play on the notion of ‘the Indigenous’ but mix it with the urban by having the artist wear a hoodie. Look here at the range of botanical references in this series overall, and the various moods created by making head ornaments from shrubs and trees. The plants and their placement on the artist’s head talk of interiority and psychological identification (due to their proximity to the cranium) as much as exteriority of culture, community and symbolic coding.

Easily the highlight of the show in my view is Michael Cook‘s set of striking handcoloured b/w photographs (inkjet prints), called Civilised. These are ‘first encounters’ on a beach, six images of Indigenous models wearing colonial costumes and standing in a foaming tide. They are accompanied by two or three lines of writing in cursive text, apparent observations (sometimes dubious) by early European visitors pondering about the human-ness or cultural sophistication of the locals. The colour is super delicate and the text choice forces you to ponder about the writers.

This is an interesting and varied exhibition that provides plenty of historical information (via pamphlets and labels) to think about in a prolonged fashion. Rich in pithy (and occasionally histrionic) postcolonial content, it is visually enticing too. There are lots of beautiful patterns and tonal matchings. Even just speculating about the regional styles is rewarding. (For example, one linocut by a Torres strait Island artist, Alick Tipoti, looks decidedly Indonesian.) Disturbingly blunt and in-your-face, but also playful, whimsical and optically seductive, My Country should not be missed.

John Hurrell

Advertising in this column

Advertising in this column Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

This Discussion has 0 comments.

Comment

Participate

Register to Participate.

Sign in

Sign in to an existing account.