Andrew Paul Wood – 15 October, 2023

Certainly, Walters saw himself in that international modernist context, and Pound argued strongly for any genealogical relationship found within Walters' koru forms being largely irrelevant to the formalist and optical transcendence of what he had done with them. But then Walters wasn't coy about having a bob both ways. For all his talk of formal “dynamic relations”, he was also emphatic that he was “not a European” and supplying some of the later works Māori titles.

Auckland

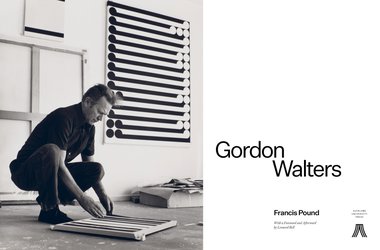

Francis Pound

Gordon Walters

With a Foreword and Afterword by Leonard Bell

Page Lay-out: Inhouse

Hardback, 464 pages, 27.0cm x 20.5cm

Auckland University Press 2023

Francis Pound was undeniably the expert on Gordon Walters and his monograph on the artist (not, to be sure, a biography) was a labour of love and decades. No one has ever put Walters under the microscope in quite the level of magnification that Pound did. Unfortunately, Pound, who died in 2017, was unable to finish it, and so the task of seeing it through went to the no less erudite Leonard Bell.

Pound and Bell had known each other since 1966. In many ways, what Bell has to say about the process of completing this magnificent (450 pages) tome, is no less interesting than the book itself. It is well worth reading the essay he wrote about this for Auckland Art Gallery.

The writing is never dry, often thrilling, and bordering on literary triumph. I have made a pact with myself to stop using the cliché “lavishly illustrated”, but it is that. Pound was a noted lover of footnotes (sidenotes here) and the reader will find them in profusion, though their marginal constriction and pale grey ink makes them a bit of a struggle to read at times. Once Pound gets up a head of steam, the reader is likely to find themselves smothered like the minions of Heliogabalus in rose petals.

At the heart of this book is the debate around what modernism means in Aotearoa, and to a lesser extent, what does modernism mean to us now - a conversation that simply cannot be held without Walters front and centre.

Academic monographs on New Zealand artists are a rare indulgence, not being overly marketable to a mainstream audience with a preference for narratives. There was something of a flutter in the early 2020s: the two volumes on Colin McCahon, Luke Smythe’s book on Gretchen Albrecht, Christina Barton on Billy Apple.

A major Walters exhibition, Gordon Walters: New Vision, the largest since the 1980s, opened at Dunedin Public Art Gallery less than a month after Pound’s death. It would be interesting to know, were Ouija boards more reliable, whether his seeing all of that work together in one place might have changed the book we now have.

Early on, something which Pound addresses with far greater depth and detail than Gordon Walters: New Vision bothered to do, was the importance of Theo Schoon as a sort of Virgil to Walters’ Dante, guiding Walters through the underworld of European modernism (Albers, Klee, Braque, Herbin and Capogrossi) though Walters was just as likely to seek out his own sources and influences, and his spin was always dramatically different to Schoon’s.

More importantly, Schoon drew Walters’ attention to the Māori rock art of South Canterbury and the drawings of mental health patient Rolfe Hattaway (though we may legitimately wince at the anachronistic title of chapter seven: “Walters and the Art of the Mad”). Both of these sources proved highly fertile in Walters’ investigations, as did his 1950/1951 trip to Europe—the Damascene epiphany. This Pound lays out in exceptional detail, having gone to great lengths to determine where exactly Walters would have gone and what he most likely saw.

Another point of particular interest is the decade and a half of Walters’ self-imposed internal exile, while he digested what he saw in Europe and developed his mature style. Things get a little spicy, if only for a sentence, as Pound defends himself against Nicholas Thomas’ assertion that he had invented this lacuna as some kind of marketing gimmick for his partner, the gallerist Sue Crockford, who at the time Thomas was writing [Possessions: Indigenous Art / Colonial Culture, Thames & Hudson, 1999] represented Walters.

One person’s art history is another person’s gossip.

By and large, mid-20th century New Zealand was not exactly embracing of abstract modernism in art, although I think that when one looks at what was going on in the decorative arts, New Zealanders were not entirely averse to it.

And lo! In 1966 Walters returns, showing the koru paintings for which he is best known at Frank Hos’ New Vision gallery in Auckland, the product of endless experimentation. To my mind, at least, the koru paintings are a mixed blessing as legacies go—an albatross around Walters’ neck that tends to overshadow Hattaway-inspired “en abyme” and “transparency” (Pound coinages now solidly in the NZ art lexicon) works.

I have a fondness for the latter two. They anticipate the flamboyant playfulness of 1980s postmodernism-probably because they exist at a chronological remove from modernism in the way Walters exited at a geographical and cultural remove. Walters was at a chronological remove as well. The modernism he was studying was already a generation old (Mondrian died in 1944).

Now the elephant in the room. Since the Headlands exhibition in 1992, the relationship between Walters’ koru paintings and Māori visual culture has, to one degree or another, have been problematised. Pound, throughout his career, made it his mission to force a break between New Zealand art and smug romantic and solipsistic landscape-based regionalism, moving it towards an international context.

Certainly, Walters saw himself in that international modernist context, and Pound argued strongly for any genealogical relationship found within Walters’ koru forms being largely irrelevant to the formalist and optical transcendence of what he had done with them. But then Walters wasn’t coy about having a bob both ways. For all his talk of formal “dynamic relations”, he was also emphatic that he was “not a European” and supplying some of the later works Māori titles.

The problem that Pound either never really appreciated or chose to ignore, is that international context was, and is, primarily, a Northern Hemisphere one, and that other worldviews—such as that of Māori—might be equally legitimate, and take a very different view of that genealogy, or rather, whakapapa. Something which Bell in his foreword and afterword seems more attuned to.

Commentary at the time tended to ignore any Māori connection at all. The New Zealand Herald review’s headline was, “Between Op Art and Geometry”. This prompted Arena Teira to write to the editor, commenting, one senses approvingly, that Walters had used a traditional Māori motif.

“Of course,” Pound writes in response, “the Māori motif is not a horizontal stripe ending in a circle. It is a multi-directional, curving stem ending in a bulb shape. The horizontal stripe with a circular terminus is Walters’ invention.” This is a little like telling a Māori whanau that one of their mokopuna isn’t theirs because it physically takes after a Pākehā parent in appearance.

Elective affinity is still affinity, and one should always be open to the possibility of anti-intentional readings having their own legitimacy. As a stance it doesn’t even really reflect with absolute fidelity what Walters himself said, which Pound cites further on:

The motif used in many of my recent paintings, a horizontal stripe ending in a circle, is not the koru of Maori art, though it is related to it [italics mine]. The Maori koru is a curved, rhythmical form, and in this respect differs from the geometrical motif employed in my work.

The specifically Maori influence on … the motif is the principle of repetition. But even here I do not use it in the Maori way. The motif is used to establish a system of relationships that follows a logic quite foreign to Maori art.

The issue seems to me to be a disagreement between two cultural worldviews over the definition of “relationship” in a sense very familiar to Tiriti o Waitangi scholars, because Māori understand all relationships in the context of whakapapa rather than resemblances, removals and acquaintances—and property to exist in collective ownership—thus it is perfectly possible for two legitimate understandings to co-exist.

Mind you, given Walters’ partner was the anthropologist, translator, author and editor, Margaret Orbell, it would be odd if he did not have a more nuanced understanding of that context. He seems to hint at something of the kind in the “Genealogy” paintings of the early 1970s. It’s astonishing that in devoting several pages to these works, Pound didn’t pick up on the potential in the title.

There is also the fact that Māori also produced rectilinear geometric motifs in, for example, kōwhaiwhai, so there is no reason to assume there wasn’t potential for a rectilinear Māori koru to develop on its own, and that any determination of what is and isn’t natural to Māori visual culture is an entirely a Pākehā and out of date projection, with little reference to what Māori themselves might think about it. For a more general discussion of these issues, I highly recommend James Elkins’ The End of Diversity in Art Historical Writing: North Atlantic Art History and its Alternatives (De Gruyter, 2020).

Paradoxically, it was Walters’ wanting to have his cake and eat it too that created a rich visual vocabulary that informed government and corporate logos for decades, and still provide a point of reference for Māori artists. Partly this was down to Walters’ influence working at the Government Printer as a layout artist and designer, and as senior artist in charge of the art department from 1957 to 1966. Indeed, Walters didn’t become a full-time artist until 1976.

This is somewhat ironic, given Walters once said, cited by Pound: “My point of departure was the koru motif. The familiar form of this motif, so widespread in Maori design as to be almost invisible, must be known to all New Zealanders, and one had to look beyond the boredom of its use in applied art to see it afresh.”

In his book, Pound makes a respectable argument for Walters’ sincerity in his process over the late 1950s and early 1960s of developing his koru-inspired form. It’s not something I especially wish to relitigate here, but personally I take a middle position between Pound, and, say, Rangihīroa Panoho’s excoriation of Walters (Why Panoho should praise Schoon, who pretended to all sorts of knowledge of tikanga, and damn Walters, who didn’t, has never been particularly obvious to me).

Robert Leonard once pointed out [“Gordon Walters: Form Becomes Sign”, Art and Australia vol 44, no 2, 2006] that in the twenty-first century Walters’ “koru” paintings are so inextricably bound up in their relationship to Māori art and the appropriation discourse, it “has blinded New Zealand audiences to the way they operate as paintings, their formal-phenomenological concerns.” Given all the flexing space of a huge and weighty monograph, Pound allows us to see these works afresh in a far broader context of concerns, even if I don’t agree that they are free from original sin.

Qualms aside, Pound masterfully brings together 60 years of Walters’ development as one of New Zealand’s most important artists of the twentieth century—each phase and influence. It is a beautifully designed book—as most AUP books are—but then, it is very difficult to make a mess of it when Walters’ work lends itself so perfectly to graphic design. Bell is to be praised for putting the final objective touches on this magnificent monument to his friend.

Andrew Paul Wood

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects Advertising in this column

Advertising in this column

This Discussion has 0 comments.

Comment

Participate

Register to Participate.

Sign in

Sign in to an existing account.