John Hurrell – 30 January, 2024

'Urgent Moments' trumpets the considerable achievements of Letting Space, and rightly so—for Jerram and Amery are a formidable team with an aptitude for attracting a great many extraordinary artists. A few daffy ones are thrown in but overall the hit-rate is very high. And the book has more distanced, balanced evaluations than what one might initially anticipate. Packed with terse inserted synopses that contextualise Aotearoa’s social history year by year, it provides a focussed tool for future generations—if there are any.

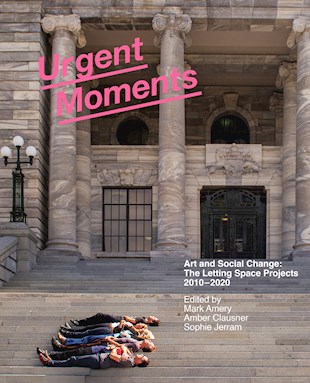

Urgent Moments (Art and Social Change: the Letting space Projects 2010-2020)

Mark Amery, Sophie Jerram, and Amber Clausner: editors

Discussions of Letting Space projects. Plus, several wider, more thematically expansive, essays.

Apart from the editors, there are also 35 other writers, including Sally Blundell, Pip Adam, Anna Brown, Heather Galbraith, David Cross, Chris Kraus, Lana Lopesi, Andrew Clifford, Melanie Oliver, Andrew Paul Wood, Martin Patrick, Reuben Friend, Ali Bramwell, Megan Dunn and Zara Stanhope.

Design: Anna Brown

Softcover, generously illustrated, 352 pp

RRP $65.00

Massey University Press, 2023

This surprisingly hefty and dense softcover book is designed to celebrate seven years of urban political (non-gallery) art projects curated by Letting Space (co-directors Mark Amery and Sophie Jerram) around Wellington—and occasionally Christchurch, Auckland and Dunedin—during the Key/English periods of National government. Urgent Moments provides a vast range of in-depth commentaries on an immensely varied conglomeration of urban projects by artists and temporary artist organisations.

As a richly informative and attractive source of documentation, this beautifully designed complex publication that focusses in detail on 25 sets of public art projects, will inevitably spur on future such undertakings, as the need for strident political activism in Aotearoa escalates with a relatively new right wing coalition government, and many global climate, ecological and economic catastrophies continue to loom around the corner.

Urgent Moments trumpets the considerable achievements of Letting Space, and rightly so—for Jerram and Amery have worked as a formidable team with an aptitude for attracting a great many extraordinary artists. A few daffy ones are thrown in but overall the hit-rate is very high. And the book has more distanced, balanced evaluations than what one might initially anticipate. Packed with terse inserted synopses that contextualise Aotearoa’s social history year by year, it provides a focussed tool for future generations—if (from the above) there are any.

As you can tell from the title, the emphasis is on functionality and efficacy, blended with the aptness of immediate action when attempting to solve pressing practical problems; not surprisingly there’s little emphasis on nihilism or impulsive emotional gesture—though they aren’t invisible.

Published several years after the last Letting Space projects, and seen from the current extremely precipitous time nationally and globally, the events elucidated in the book are a rich and stimulating brew, with 38 writers and over 50 artists. The publication is an elegant tome that successfully blends visual appeal (lots of images) and accessible information. Its fine detail, copious footnotes and extensive interconnected lists, is remarkable, using careful organisation and surprising variation in performance/installation art types; a real pleasure to randomly dip into.

Yet curiously, for all the vast quantities of thoughtful writing that’s included, the publication’s contents section is possibly too artist project oriented (not sufficiently individual writer focussed)—a decision that hampers the book’s use if you wish to methodically quickly track down the authorial contributions. The contents pages are over brief, and should (I think) have included all the writers by name, with page numbers given. However there is an advantage in that the reader in forced to dig into the different sections and pry out those articles of immediate interest early on—before discovering other treasures. (Incidentally I’m very proud of the fact that several EyeContact reviews of Letting Space projects are given a re-airing. They hold up extremely well.)

It might at this stage be appropriate to remember the activity of a smaller-scaled precursor in South Island Art Projects (SIAP)—first director: Jude Rae—a CNZ funded organisation of the very early 90s, a non-gallery art project based in Christchurch (broader in interests, less exclusively political or relational) that eventually transmuted into The Physics Room exhibiting space. That latter (you could argue ‘compromised’) transmutation speaks of the failure of non-gallery sites to attract conventional art audiences, viewers with a consistent history of checking out art seriously—so this Letting Space publication is an impressive counterargument, showcasing a goodly number that will be remembered for having social impact.

Some official Letting Space projects though lacked wallop, but made up it in satellite projects. For example, Judy Darragh’s 2014 Letting Space installation in downtown Queen St (in the darkened environs of JWT Advertising offices) of Darragh-aestheticised ‘begging bowls’, would have attracted far less viewers and stimulated less conversation than her show of enlarged ‘mendicant signs’ in Two Rooms held a pinch earlier—a much more confrontational gallery show that as such was not officially part of the Letting Space programme. Overall in this book, readers are presented with an impressive range of instigated projects, including the complex 2015 Transitional Economic Zone of Aotearoa (TEZA) based in Porirua.

Here are seven Letting Space projects that really caught my eye, greatly appealing to me personally via my own, mostly idiosyncratic, aesthetic visual enthusiasms.

Eve Armstrong’s Taking Stock (2010) is a work with both a performative and an exhibition aspect, involving the public collection, transport and temporary display of hard, translucent or white, recyclable and abandoned plastic products. In 2010 such plastic detritus was taken from various collection sites and paraded in wheeled barrows (or carried by hand) to a building in Featherston Street where it was displayed in long upper-floor windowed rooms. The following year the same process was repeated, except that the material was eventually carted to City Gallery Wellington where it was exhibited as part of the 2011 Prospect exhibition.

Another project I consider to be brilliant because of the sheer physical scale of her ambition, is Siv B Fjærestad’s 2015 Projected Fields. This artwork involved collecting questionnaire community data and transmuting it into huge circular paintings (of statistic-based coloured graphics) rendered on large public parks around Wellington and viewable in their frontal entirety only from the air, or seen squashed and foreshortened from the land. There was a clear link between the final visual images and a body of answers responding to a earlier set of structured questions about park use and site history.

Rana Haddad and Pascal Hachem’s Unsettled contribution was a set of two 2017 performances in the heart of Wellington. Two Lebanese artists doing an international residency, they organised the making of long ‘eiderdowns’ or narrow ‘blankets’ of densely stitched together items of clothing that could be made into portable rolls. These could then be publicly unfurled on city pavements, while delineating the positions of two underground streams, starting at the sources and heading to the sea. The clothing-lined ‘duvets’ could then be cut up and used. They referenced Wellington’s high number of Māori homeless, along with a local poetic aphorism from a helpful kaumātua that in translation said, “When you daylight the streams, you daylight the people.”

Part of A Common Ground Pop Up Project, in Hutt Valley, Gabby O’Connor’s Drawing Water: Low Lying (2017) created the ‘mapping’ of a wide network of underground streams, using intertwined lengths of orange rope, held in position on the floor via white cable ties. As you can see from this link to a Corbans Winery version, https://tempauckland.org.nz/water/, all sorts of scientific experts were called in to assist a large group of students.

One very unusual project was Bronwyn Holloway-Smith’s Te-Ika-a-Akoranga (2014). She initiated the repair and reinstallation of a dismantled (and abandoned)1962 coloured tiled mural by E. Mervyn Taylor, normally famous for his wonderfully detailed b/w woodcuts of landscapes, Māori legends, birds and plants. His ceramic masterpiece was originally installed in the foyer of the Compac Cable Station in Northcote, Auckland, and was designed to celebrate the Southern Cross undersea cable that enters the sea at Takapuna Beach. Holloway-Smith asked around and was shown the tiles abandoned in three cardboard boxes. She then contacted the Taylor estate. The fully restored version (gradually installed in sections as a performance work in progress) is now in the Takapuna Library.

The most spectacular work, in terms of efficacy in helping the needy, was Kim Paton’s extraordinary Free Store (2010) which enabled the effective and generous distribution of free food and goods to those urgently in need, often focussing on edible products with a palpably approaching use-by date. A work with stunning public appeal, the project demonstrated unheard-of co-operation between rival companies Progressive Enterprises (which provided much of the unpriced produce) and Foodstuffs (enabling the rent-free premises). The donated and very diverse edibles came with a negotiated, safe and harmonious solution for expiry dates and waste disposal, usually accounted for diffferently in store pricing.

On a more humorous note, Julian Priest’s Free of Charge (2012) interactive sculpture presented a freestanding vertical portal, a metal frame for participants to pass through, that was akin to the scanning device that you find in international airports. Positioned outside between adjacent fenced off grassy ‘zones’, measured each attendee’s electrical charge, and that by stepping on solid earth on the other sides they were ‘free of charge’ and ‘grounded’, a pun on no cost and no impactful electrical ions. It mocked governmental bureaucracy and visitor paranoia while exuding an air of mischievousness—attacking any sort of travel as undesirable corporeal circulation, and nuttily encouraging stasis. It also had a hint of satire in its evaluation of new age ‘wellness’.

I liked this work because passing through security screens at airports is an exasperating experience we all are familiar with. A contrasting, yet vaguely similar work (in terms of interactive public sculpture) was Vanessa Crowe’s Moodbank Wynyard (2015) which in contrast I found utterly perplexing. Its basic premise, that positive or negative emotions can theoretically be stored as if consistently stable transferable qualities, I find incredibly strange—a form of cynical sci-fi mocking the notion of hope or future planning on the part of any individual. I may have missed the point. Maybe I didn’t?

Of the many written contributions to this book, my clear favourite is the exceptionally lucid Giovanni Tiso piece on Tao Wells’ Beneficiary’s Office (2010). Today, in the current age of effortless media manipulation (exemplified by the hideous Donald Trump), Tao Wells’ behaviour looks self-indulgent in its provocation, and possibly damaging public relations for other performance artists with serious political motives. While to me Amery and Jerram initially looked naïve in taking Wells on, Tiso’s fascinating account encourages a reconsideration of Wells’ use of a ‘Wells Group PR’ office, street banners, and other ‘incendiary’ tactics. It is richly detailed, carefully researched, pleasurable journalism that can be pored over again and again. Its presence testifies to Jerram and Amery’s skill in putting this publication together.

John Hurrell

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects Advertising in this column

Advertising in this column

This Discussion has 0 comments.

Comment

Participate

Register to Participate.

Sign in

Sign in to an existing account.