Norman Franke – 5 March, 2024

While in traditional European cities you find a carved saint on every bridge, and a sculpture in every major building or fork in the road, and in equivalent Asian cities myriads of temples, shrines and places to be encountered for contemplation, in many modern societies the everyday and spiritual dimension of art and the awareness of the 'mana' of places and objects has been almost completely lost. Much of modern (Western) art is critical, ironic, and even polemical, and not always easily accessible to general audiences.

Kirikiriroa Hamilton

Susannah Salter, Barbara Wheeler, Susan Nelson, Anya Whitlock, Laurette Madden Morehu, Simi Paris, Chris Moore, Wanda Gillespie, Sarah Bing, Te Rongo Kirkwood, Natalie Guy, Peata Larkin, Salome Tanuvasa, Stuart Bridson, Julie Moselen, Gaye Jurisich, Dale Cotton, Gina Ferguson, Louise McRae,

Antoinette Ratcliffe

Our Place

3 February - 31 March

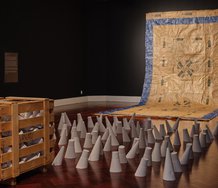

Our Place, an exhibition of diverse sculptural art runs parallel to the outdoor installations of the Boon Sculpture Trail. Both shows overlap with the Hamilton Arts Festival, which showcases music, theatre and other performance-based art forms. As Nancy Caiger, the Project Leader of the Boon Sculpture Trail says in an accompanying brochure, the overall aim of all three is to create artistic synergies: “[The sculpture exhibitions] will add to Hamilton’s attraction on the national art scene and as a tourism destination…, while giving a fresh lease of life to the existing public art collection…” (1)

Most of the creators of the 60 small to medium size works featured in Our Place have also larger sculptures in the Boon Sculpture Trail, a complementary show of outdoor works in the city about to be reviewed by Peter Dornauf on this EyeContact site.

As for the ArtsPost exhibition, Our Place, there is a wide range of different approaches and procedures at work here: from geological and geographical interpretations of the topic to socio-cultural ones, from realistic modes of representation to symbolic and abstract variations. By and large, the focus is more on the artists’ individual perspectives of ‘place’ rather than on collectivity. The plural in Our Place seems to be slightly underrepresented in collaboratively created works and also in terms of actual community loci, situations or interactions represented.

Having said that, it is a great achievement to assemble such a wide range of works and to make them available free of charge to the wider public. In (post-)modern times like ours, when the traditional agencies and sponsors of public art such as religious communities and city councils often reduce art to decoration and conceive of the arts budget more of an expenditure than an investment, this public arts initiative deserves much praise.

While in traditional European cities you find a carved saint on every bridge, and a sculpture in every major building or fork in the road, and in equivalent Asian cities myriads of temples, shrines and places to be encountered for contemplation, in many modern societies the everyday and spiritual dimension of art and the awareness of the ‘mana’ of places and objects has been almost completely lost. Much of modern (Western) art is critical, ironic, and even polemical, and not always easily accessible to general audiences. Paradoxically, ‘public’ art has become a niche culture, its distribution and function greatly reduced. Any attempt to bring art back into the public space, to make a selection of works that combine criticism and humour, and also contemplation and the celebration of beauty, is all the more to be commended.

I will now highlight a few of the many outstanding works of the Our Place exhibition to hopefully encourage art lovers and collectors—all pieces exhibited at ArtsPost are for sale—to take a close look. They might like to get in touch with the artists for further information or inspiration.

Peata Larkin’s installation, What binds us, presents what might be the aerial view of a waka, a sociogram or a suspended tabernacle. Through acrylic, pigments, mesh and flexiface membrane on a LED Lightbox, the artist’s illuminated installation invokes a sense of communal endeavour and interaction with the environment.

Anya Whitlock’s Fabric Phantom Deer, fabric on fiberglass, is a tongue-in-cheek take on middle New Zealand’s obsession with hunting and fishing. As in her large-scale sculpture Huia for the Boon Sculpture Trail in front of the PwC Center, the outlines of the animal are ‘realistic’, but the surface is a subtle play of colour and shape that gives the overall impression of both loss and psychic aura.

Chris Moore’s statue, Bloom, is one of the smallest art works ln the show, but its shape and proportions achieve an archetypical perfection that attracts the visitor’s attention. Where have we seen the sculptural depiction of a tree sapling or branch like this before? In the hands of an ancient Greek hero? In a Waikato garden?

From 67° NE 39° 12‘58”S 175°/40‘35”E to 306° NW39° 1‘16”S/175° 42‘52”E to 26° NE 37°/ 23‘9”S 174° 43‘14” E — no one is more precise about where Our Place is located than Gina Ferguson. The coordinates translate into From Tongariro 1100 m Altitude to Taupo 570 m Altitude to Port Waikato 0 m Altitude. Her huge pumice necklace on stainless steel wire befits the many taniwha that grace the waters and lands lovingly maintained by the Waikato awa.

Made from ceramic, glaze, gold lustre and acrylic, Sarah Bing’s Blue Mamba is a flamboyant, life-size female torso that subtly hints at the artist’s trademark bright colour and playful shape. With a fringed lamp shade for a head, the figure, which combines both glamour and parochialism, is conceivably a parody of many a Waikato pub.

Antoinette Radcliffe’s arrangement of dead animals Untitled (black cat and canary) has got a morbid touch to it. A memento mori (remember you must die) and a nod to Tennyson’s description of nature as ‘red in tooth and claw’—as well as to animal cruelty—the artist assures us that her media are ‘ethically sourced taxidermy’.

Aligned is a fine metal statue by Julie Moselen, made from Corten steel and 23 c gold. It consists of two free standing beams of steel that are a little twisted as if they are engaged in an embrace or a dance. Symbolic perhaps of a dialogue between two persons or esoteric forces, where the most precious, intangible space of alignment happens in the ‘in-between’. The work is a masterpiece of craftsmanship and meaning, for the reviewer felt reminded of Martin Buber’s I and Thou: ‘All real living is meeting.’ Of all the objects of the exhibition, Aligned’s aura was the hardest to capture in a photograph.

Susannah Salter’s stylized figurines are made of local low fired clays and porcelain. They bear names of human archetypes and philosophical ideas such as Protector, The Truth, Curiosity, and Audacity. The symbolic forms are arranged as a group and, depending on your perspective, they develop different but always impressive spatial dynamics. This concerns their aesthetic interplay as well as the interaction of the basic philosophical ideas and traits they represent.

A traditional wood carving of a young woman’s head by Wanda Gillespie, We are made of Stardust, forms a soothing resting point within the exhibition’s vibrant arrangement of formal inventiveness, as the image’s forces of serenity and energy are finely balanced. As the woman’s hair grows from the elemental power of the wood, and her facial features show a smooth, almost ethereal dimension and a star-shaped tattoo, it seems as if the oeuvre’s form and refinement have long since resided in the tree that once connected the earth and night sky.

Norman Franke

(1) Nancy Caiger, in: Caiger and Ulenberg (eds.), Boon Sculpture Trail 2024 Shape-shift Your Summer, brochure, Hamilton 2024, p.5

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects Advertising in this column

Advertising in this column

This Discussion has 0 comments.

Comment

Participate

Register to Participate.

Sign in

Sign in to an existing account.