John Hurrell – 22 June, 2010

What is interesting about the book is the deliberate mixing of opposites, using design qualities as camouflage so that the contradictions are not easy spotted - but nevertheless aiming at a sort of objective truth. A Zionist campaign song (words and music) about Israelis coming home to Palestine is included with drawings that attack Israeli settlement in occupied territories. Other drawings attack religious persecution in the Soviet Union. There is even a letter from a Bolshevik magazine attacking women's right to have ‘freedom of love' - a companion to one of the films that looks at the statistics of rapists.

et al. publication

Critical Remarks on the National Question

Texts by Vladimir Lenin, Karl Marx, et al., Jan Bryant, Jennifer Hay, Methodists, Presbyterians and others.

Sub-editor Gwynneth Porter

Photography: David Watkins

Concept and design: Narrow Gauge

200pp, black and white / coloured illustrations

This compact hardcover book ostensibly reflects the complicated layered structure of the exhibition that’s obvious! that’s right! that’s true! which et al. presented in Christchurch Art Gallery last year, but in fact it is much more interesting than that. It is a good looking and immensely interesting read. It is to my mind clearly the best catalogue we have seen for an et al. exhibition so far. Far better than say the larger but glossier and floppier Fundamental Practice, the Venice document, and arguments for immortality, created for the Govett-Brewster survey. The interwoven written and visual content is much more focussed, and Narrow Gauge’s graphics and organisation are superb. The tome and its pages have a lovely weight and feel to them - like a sixties highschool social studies textbook. It seems like, and indeed is, an artwork on its own - outside of the installation it is documenting. It is geared to presenting various related ideas to a reading audience who may not have seen the show in Christchurch.

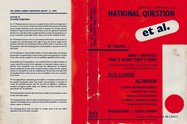

This medium-sized book has a red, black and white cover derived from the New Zealand Communist Review of the sixties and modelled vaguely on various early socialist leaflets that have been loosely sequenced in the form of twelve ‘letters’.

Included prominently within this structure are the distinctive drawings that played a crucial role in the exhibition, works that are made to be read as much as looked at - taped over layers of translucent paper that have been scrawled and ruled on, typed, stamped, collaged and (characteristically) erased. The language filled charts and statistical diagrams reference some kind of international human rights agency presenting statements augmented by unexpected slogans spiced in from Christian, Marxist and Buddhist sources - amongst others.

Then there are the sets of mainly black and white film images from the four films shown next to four portable polling / viewing booths. They show the silhouetted pencil of an instructor who with an overhead projector develops the central but highly ambiguous trope of the show - that of a building’s floorplan. It is seen everywhere in the exhibition - as white taped rectangles on the gallery floors; as little models in glass tanks and films; as publisher’s logs throughout the book. Amongst other possibilities this ubiquitous architectural diagram stands for charitable organisations, Palestinian housing compounds, various community institutions, the individual self or brand, and nation states.

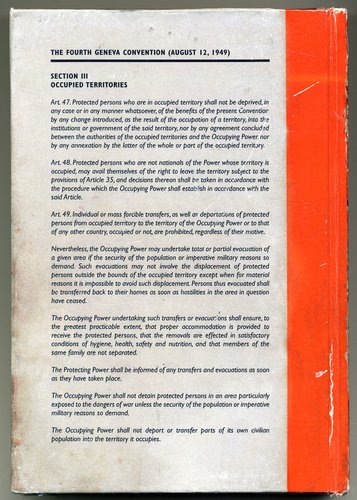

Included and mixed in with this metaphor are Lenin’s 1919 tract about bourgeoisie asset confiscation, Marx’s 1867 analysis of surplus-value, the Fourth Geneva Convention statutes on occupied territories, some drawings that focus on religious persecution and a Methodist /Presbyterian statement about the Treaty of Waitangi and the concepts of tino rangatiratanga (Maori sovereignty) and kawanatanga (more limited governorship). These threads are underscored by the inclusion of a comic drawn with blue carbonpaper on democracy in Iraq (that starts as a religious tract), and a list of 88 internationally known, charitable trusts (with assessments and descriptions) to most of which the reader can donate money.

What is interesting about the book is the deliberate mixing of opposites, using design qualities as camouflage so that the contradictions are not easy spotted - but nevertheless aiming at a sort of objective truth. A Zionist campaign song (words and music) about Israelis coming home to Palestine is included with drawings that attack Israeli settlement in occupied territories. Other drawings attack religious persecution in the Soviet Union. There is even a letter from a Bolshevik magazine attacking women’s right to have ‘freedom of love’ - a companion to one of the films that looks at the statistics of rapists.

Some of the writing goes in the opposite direction. Instead of exploring fragmentation and paradox it aims at totalizing via an overarching symbolism, especially in regard to the gallery installation. One author (called ‘aliquem alium interim’) describes part of the exhibition’s ramp with voting box (it is pictured alongside) as a double barricade that repeats the structure of Marx’s materialist dialectics while running as a rampart that goes from east to west like Hegel’s notion of history. It also has three steps on either side (with three megaphones) that refer to Marx’s three voices (as discussed by Lenin): historical materialism, political economy and scientific discourse. Every detail in the exhibition seems symbolically predetermined in advance, with no irony lurking within the didacticism.

This is a particularly well resolved publication (considering its complexity) with none of the self-congratulatory smugness (discussing et al. as artistic entity) that marred the Venice and Govett catalogues. It happily zeros in on the work, broadening the show’s concepts, and is well worth getting - if only for its many illustrations of et al’s extraordinary diagrammatic, paper and sticky tape, drawings. Or the fascinating essay by Jan Bryant on the exhibition’s connection to Spinoza, altruism and charity. In all, a remarkable achievement.

John Hurrell

Advertising in this column

Advertising in this column Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

This Discussion has 0 comments.

Comment

Participate

Register to Participate.

Sign in

Sign in to an existing account.