John Hurrell – 11 June, 2010

The controlled lighting used for each cast, along with the plaster bust's detail and scale, creates an intimacy that makes viewing each face an encounter across time. The fact that Dumoutier and d'Urville themselves are represented alongside Pitani from the Solomons, Koe from Timor, Orion from Papua New Guinea, Tou Talua from Samoa, Matua Tawai and Tangatahara from Aotearoa and Eugenie Sauvage, a young French woman, introduces a lack of hierarchy that makes this collection of images compelling.

Auckland

Fiona Pardington

Ahua: A Beautiful Hesitation (downstairs) The Language of Skulls (upstairs)

Curator: Kriselle Baker

24 May - 3 July 2010

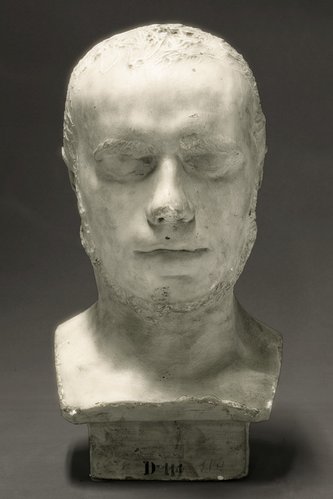

Hot on the heels of Fiona Pardington‘s popular show in the Sydney Biennale (of similar but much bigger works) these two exhibitions take up both of Two Rooms’ two rooms. The two displays are quite different: one is of her photographs of life casts of human heads made in the Pacific region during Dumont d’Urville’s last exploratory voyage of 1837-40 by the phrenologist Pierre-Marie Alexandre Dumoutier (1791-1871); the other is photographs of life casts that have been used to make three-dimensional phrenological charts, with the plaster heads being painted over with gold and other colours to be then drawn over to demarcate certain areas of the skull surface, these being allocated to various emotions, social behaviours and thinking types.

When Dumoutier returned to France in 1840 he brought with him fifty one casts (many of which Pardington has photographed at the Auckland War Memorial Museum, the Musee Flaubert d’Histoire de la Medecine in Rouen and Musée National d’Histoire Naturelle in Paris) and the same number of skulls. He believed profoundly in the unity of the human species, that humankind originated from one source, and so was shaken by the diversity of peoples he encountered on his trip. Three of his naturalist colleagues on the same boat had their own alternative theories, and interpreted Dumoutier’s bust collection and the people he used quite differently.

One, Jacque Bernard Hombron linked diverse origins with divine creation by proposing that there were ‘three natural families’ - black, copper-coloured and white - each group still living at their point of origin, but listed here in increasing intelligence. His colleague Honoré Jacquinet, on the other hand, also believed that there were three separate human ‘families’ but that they were all equal in capability. The third naturalist, Emile Blanchard, had six types arranged in descending order of intelligence, with the European at the top and the Polynesian and African Negro at the bottom.

With Pardington’s project, whilst it would be fascinating to see an artist make facsimiles from Dumoutier’s busts (i.e. sculptural replicas made as a conceptually and historically ‘purer’ undertaking), with her delicately nuanced colour photography Pardington provides something else. The controlled lighting used for each cast, along with the plaster bust’s detail and scale, creates an intimacy that makes viewing each face an encounter across time. The fact that Dumoutier and d’Urville themselves are represented alongside Pitani from the Solomons, Koe from Timor, Orion from Papua New Guinea, Tou Talua from Samoa, Matua Tawai and Tangatahara from Aotearoa and Eugenie Sauvage, a young French woman, introduces a lack of hierarchy that makes this collection of images compelling. Inevitably we look for qualities like ‘sensitivity’ or ‘amusement’. We attempt to ascribe psychological properties to the owners of the faces that formed these busts.

The upstairs exhibition is not of portraits but of schematic diagrams drawn on painted casts that attempt to universalise traits, through analysing the positions of cranial bumps. The battered and chipped generic busts have a decaying beauty and look oddly as if they have been decorated with the linear configurations of Art Nouveau. On their heads are handwritten pen and ink words or trimmed paper strips of printed lettering, terms for emotional qualities or abstract nouns. Amongst the images are four shots of a bust made by Franz Joseph Gall (1758-1828), phrenology’s founder.

The funny thing is that even though phrenology overall is now considered to be totally bogus, the endeavours of people like Dumoutier helped to found anthropology, and some aspects are vaguely correct. Certain areas of the brain for example are now acknowledged to be linked to definite personality attributes but they are truly inside the skull, not related to the undulations of its thick boney surface.

These shows of Pardington’s are absorbing, particularly Ahua: A Beautiful Hesitation - the larger downstairs exhibition. This is not only because seeing these hundred and seventy year old faces is immensely moving but also because you invariably speculate about how Dumoutier persuaded his subjects to put up with the discomfort of having the casts made. Apart from issues for some of the sensitivity of the head as a tapu ‘body zone’, did they have to breathe through straws poked in their nostrils or was the setting of the ‘female’ cast very quick? Did he bribe them with weapons, utensils or clothing? Was he a man of considerable charm that transcended cultural differences?

Pardington has created a couple of terrific exhibitions here, examples of the best kind of ‘history show’ where the viewer is mentally transported. Don’t miss them.

John Hurrell

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects Advertising in this column

Advertising in this column

This Discussion has 0 comments.

Comment

Participate

Register to Participate.

Sign in

Sign in to an existing account.