John Hurrell – 6 June, 2010

Not only is the work oddly surreal, varied in references and humorously startling but it is also very physical. The delicate colour glows as if the liquid translucent hues have been applied to metallic sheets. The varnish covered painted surface has a highly reflective gloss which brings a delicate but gorgeously diffuse golden quality to the light. This makes the image slightly immaterial or ethereal.

Roger Mortimer is known for a kind of painting that exudes through its meticulous finish a link to Medieval and Renaissance craft and early illuminated books. His carefully rendered jewel-like images with their precisely placed linear motifs are not of our time, but of the sixteenth century or much earlier - even though they often reference the digital era, various contemporary subcultures, and publications like seventies record sleaves or Gothic fantasy comics. He enjoys creating an odd hybridity, blending a shallow space that links preGutenberg technology with today’s computers and satellites.

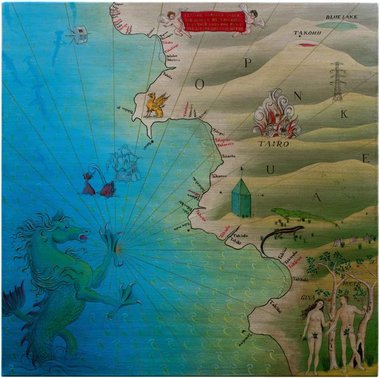

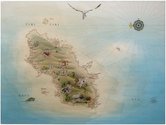

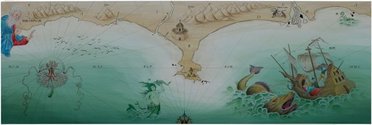

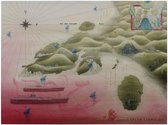

Maps, with their wobbly coastlines that Mortimer seems to enjoy creating wormcast riffs from, and the glassy sea, dominate this show: an allegorical scrambling of time and geography that pushes at the limits of the human imagination. He is the visual equivalent of a writer like Umberto Eco, an odd version of eighties pomo with its dense layering of colliding or intertwined worlds and systems.

The main visual structure that he uses in this show is that of the Portolan chart, an early variety of map developed from the twelfth century on, when sea atlases were just beginning. These were based on wind direction and used crisscrossing navigation lines for shipping routes, accompanied by verbal details written in spidery fashion along each line, and imaginatively created creatures lurking within the mountainous landforms or the depths of the sea.

Mortimer’s physical blending of Aotearoa (mainly its most western aspect, Taranaki) with what seems to be Europe is undoubtedly intriguing, but the love of history that he shows isn’t the post-colonial critique of imperialist domination or will for knowledge and power that you might expect. These fanciful cartographic images are not limited to European or Pacific environs, for there are also Asian pictographs hovering nearby, flapping batwinged monsters too, and odd digressive texts all spread across the picture plane. I suspect Mortimer simply likes drawing and assembling images; letting his mind drift to create unusual nonhistoric juxtapositions.

Not only is the work oddly surreal, varied in references and humorously startling but it is also very physical. The delicate colour glows as if the liquid translucent hues have been applied to metallic sheets. The varnish covered painted surface has a highly reflective gloss which brings a delicate but gorgeously diffuse golden quality to the light. THis makes the image slightly immaterial or ethereal. There is a beautiful flimsiness here, an appealing lack of substance - a vague hint that all this is illusory.

In fact while these works revel in fragmented mythic narratives from different periods referenced simultaneously, or take the present from this place to extrapolate and reinvent a wildly imaginative new past, I find the shiny surface and nuanced haze so sufficiently compelling that the paintings almost become ‘abstract’ - quirky cousins of say, the brightly saturated yacht resin works of Leigh Martin. They become radiant objects that exude a sort of misty field, rather than be just vehicles for telling dreamy stories. That physicality even extends to odd details like the properties of coastlines - one formal aspect that I find constantly adorable about maps: the unpredictably twitchy undulations of certain cartographic shorelines that my eye can track and which affects me profoundly like a shrill and squeaking bebop solo.

Though overtly alluding to the past these works are firmly locked in the present as experiences within the gallery space. The pleasure they provide is a traditional craft one - like that of an exhibition of glazed ceramics. Their difference though is in the sense that the logic of their skilful and seductive construction seems to be displayed alongside a celebration of ‘History is Bunk’ - a denial, an embraced illogicality, a thwarting of consistent meaning.

John Hurrell

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects Advertising in this column

Advertising in this column

This Discussion has 0 comments.

Comment

Participate

Register to Participate.

Sign in

Sign in to an existing account.