Martin Patrick – 10 July, 2010

Similarly, Truitt was once more well-known for her incisive diaristic writings published throughout the 1980s than her remarkable sculptural works, but since the renewed interest in Minimalism, Truitt has been reintroduced, along with Lee Bontecou, into historical narratives that no longer privilege solely their male peers. The critic Clement Greenberg wrote positively about Truitt's work, while Donald Judd maintained a staunch condescension: both responses did the artist few favors.

Assorted New York Dealer Galleries

June

The artist David Hammons once remarked that you encounter much more art while on your way to the gallery than you do upon arrival. I would heartily agree, although today you would encounter less of the engaging detritus that characterized Hammons’ own streetwise concatenations and more likely boutiques featuring organic pet foods, low fat designer cupcakes, and almost any other conceivable fetish item. Here of course I’m specifically addressing the utterly gentrified environment of New York City, c. 2010 AD.

The US has frequently made a point of being blithely ahistorical in its short-term, shorthand, and shortsighted worldviews, but its most lauded city is undergoing a pronounced wave of historicity and nostalgia. This is evident whether one hits its plentiful retro-style bars and restaurants, delves into its regional literature, or the art galleries of Chelsea, where a kind of aesthetic comfort zone surrounds most of the cultural products on view. Previously “challenging” commercial galleries house museum-style retrospectives, as in the case of Gagosian’s “late” Roy Lichtenstein and Claude Monet shows. One might surmise that this conservative route bespeaks post-recession damage control as much as anything.

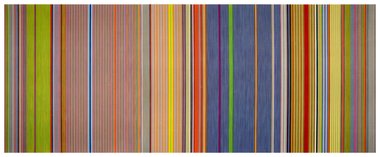

Nonetheless, a marked and welcome profusion of painterly abstraction - ever anachronistic, ever timely - was highlighted in the near-synchronous and thoroughly elegant shows of the artists Gene Davis (at Ameringer/McEnery/Yohe) and Anne Truitt (at Matthew Marks), both entirely underrated in their time, and now gaining belated entry into the continually revised art historical canon.

Davis (1920-1985) and Truitt (1921-2004) were both Washington D.C.-based artists whose work peaked during the 1960s and 70s, although critical interest in their work was mild to negligible in relation to their shared ambition, innovation, and achievement. Davis, early on a journalist, and later a fine arts teacher, specialized in large-scale paintings featuring deceptively simple and boldly emblematic patterns of alternating, brightly hued stripes. In their lushness, they are initially more seductive than confrontational.

That said, I had thought Davis’ paintings might seem old-fashioned and anemic these days, but they really hit me hard with their reverberating, aestheticized relentlessness. Of particular note was Saratoga Springboard from 1969, which operates on the wavelength of Barnett Newman’s largest works but with a lighter, near-whimsical tone. Displaced from their original context and era, Davis’ pictures floated free of the accumulated baggage of old formalist debates and seemed to recalibrate themselves for a newfound audience in a different time. Similarly, Truitt was once more well-known for her incisive diaristic writings published throughout the 1980s than her remarkable sculptural works, but since the renewed interest in Minimalism, Truitt has been reintroduced, along with Lee Bontecou, into historical narratives that no longer privilege solely their male peers. The critic Clement Greenberg wrote positively about Truitt’s work, while Donald Judd maintained a staunch condescension: both responses did the artist few favors. The current exhibition featured a tight arrangement of Truitt’s seminal hand-painted wooden plinths. They seemed to shimmer in the light and radiate dynamically through the gigantic space, commanding the attention they’ve always deserved.

Arguably the most compelling other exhibition also in Chelsea was a few blocks north at Mitchell-Innes and Nash where the transgressive and transformative performance artist, writer, and teacher William Pope.L (who has in the past designated himself “The Friendliest Black Artist in America”) presented a cluttered assortment of texts, drawings, scraps, found materials, and performative props entitled landscape + object + animal. On weekends actor/performers took turns donning masks bearing the likeness of President Obama and gripping oversized and overfilled (with green ink) coffee cups, while poised precariously on mounds of dirt for over an hour at a time.

Yet the moment of true sublimity in the space was Snow Crawl, a raised plywood platform, to be ascended by a series of narrow steps. Once at the summit, the viewer was directed to look down into a rectangular, mirrored chimney-not-unlike a giant kaleidoscope-containing a video monitor featuring footage of the artist renowned for his endurance crawls sliding around an arctic setting-I assume in small-town Maine, as that’s where the artist works-leaving patterns in the snow, creating a continual vacillation in Pope.L’s optical device between the baroque and abstract and the austere and prosaic.

A more technologically-driven hybrid of abstraction, appropriation, and voyeurism could be found on the Lower East Side at Scaramouche gallery in Oliver Lutz’s The Mediated Subject. The artist used a rather overly complicated scheme involving infra-red surveillance cameras pointing toward black monochromes so as to reveal on a bank of monitors various representational images lying underneath their surfaces. Lutz’s appropriated source material ranged from the “banal” to the “political” but generally didn’t surmount the circuitous means leading to their emergence. (My colleague David Cross quipped that the show appeared to be a mashup of Kazimir Malevich and Bruce Nauman.)

New York’s conspicuous wealth continues to cover over its weird and unfathomable cultural depths with antiseptic, superficial, and shiny surface attributes, making it arguably an even more elusive territory to negotiate than it once was. Most artists still lurk at the edges, far uptown, downtown, mostly across bridges, and dispersed across the country for that matter. But the city itself and its arts communities retain such considerable force and vibrance that it is likely to realign itself into a multiplicity of fantastical aesthetic positions yet to be determined. Or at least I hope so…

Martin Patrick

Advertising in this column

Advertising in this column Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

This Discussion has 0 comments.

Comment

Participate

Register to Participate.

Sign in

Sign in to an existing account.