Warren Feeney – 1 July, 2011

All the figures in the 12 prints in '(Un) Common Ground' are placed in a middle distance that separates them in space, just far enough away from the camera to allow them to be spied upon. They become anonymous as individuals and can be viewed with detachment and a degree of secrecy, yet equally, they are still close enough to scrutinise their behaviours.

The photo-intaglio prints that make up (Un) Common Ground might initially appear as simply familiar territory to the art of printmaking, retaining all the obsessive attention to making that usually characterise it as a serious art practice. Paul McLachlan is a meticulous and fussy practitioner, yet there is more than just method going on in (Un) Common Ground to complement and transcend the artist’s attention to process and detail.

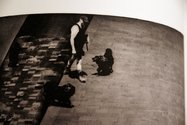

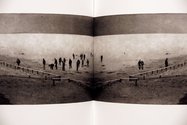

As black-and-white sequential images of figures viewed from afar, moving through the inner city of Christchurch pre-22 February, these prints invite - even encourage - an inherent voyeuristic pleasure. All the figures in the 12 prints in (Un) Common Ground are placed in a middle distance that separates them in space, just far enough away from the camera to allow them to be spied upon. They become anonymous as individuals and can be viewed with detachment and a degree of secrecy, yet equally, they are still close enough to scrutinise their behaviours. Comparisons between the viewer’s act of looking, James Stewart and Rear Window, or for that matter, any Hitchcock movie from the 1930s (Sabotage comes to mind, especially the crowd scenes), are entirely appropriate. On one level, (Un) Common Ground is constructed on the premise of Hitchcock’s cinematic voyeurism: the fake, grainy black-and-whiteness of McLachlan’s images, the sequential silent movie references and the detached distance between viewer and protagonist. The exhibition’s title is just as complicit in this plot. In some works, for example, the etched ground behind the figures isolates them from reality and a familiar experience of the world. They become - uncommon - and acceptable as subjects for our observation.

McLachlan also turns the viewer’s guilty pleasure in the act of watching, back on them with the majority of works consisting of three to four curved sequential images that forces the gallery visitor to track their gaze around each image, becoming directly involved in the work itself. McLachlan’s treatment of the print insists that they move forward from image to image with each step revealing more about the scene and its players, while obscuring moments already seen. In The Crossing, a figure walking two dogs enters from top left to middle and exits in the third image, behind his canine companions. It’s a physical journey through time and space for the figures and the viewer, as well as an orchestrated formalist study in space and tonality.

However, the best of McLachlan’s work is more than formalist, nostalgic, clever or merely skilful, rather, prints such as Kapa Haka, are genuinely sentimental and touching images, rendering private moments between public performances, with figures caught and suspended, prior to a return to life on stage. It’s an Edward Hopper moment with all the accompanying reflection and melancholy that the America realist was similarly capable of conjuring up.

Indeed, the emotional potency of McLachlan’s prints is the strength of (Un) Common Ground. The only reservation lies in works such as The Procession where the curved prints in relief from the gallery wall are visually linked as a unified series of symmetrical images. The Procession seems somewhat self-conscious and notice-me clever, highlighting the challenges McLachlan faces. How much longevity does the unframed curved sequential print as artist’s trademark retain? How long can it be sustained before it descends to formula? Fortunately, it’s a challenge that McLachlan as printmaker seems more than ready for.

Warren Fenney

Advertising in this column

Advertising in this column Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

This Discussion has 0 comments.

Comment

Participate

Register to Participate.

Sign in

Sign in to an existing account.