John Hurrell – 15 August, 2011

Although Rankin believes the work ‘is not overburdened with polemic and didactic messages', believing that these artists ‘do not provide answers to the questions they raise', only ‘reveal what they have discovered', it is a tub-thumping ‘soap box' sort of show, those ‘questions' aimed at preaching to the converted. It is not likely to persuade any rare individual who enters the Gus Fisher with contrary opinions.

Auckland

Daniel Heyman, Michael Reed, Sandra Thomson and Diane Victor

Collateral: Printmaking as social commentary

Curated by Elizabeth Rankin

1 July - 20 August 2011

Printmaking is one those activities that often gets unnoticed in an artworld usually preoccupied with more spectacular or fashionable varieties of image making, prints generally being considered more craft than art and somewhat bookish in the fusty, not cerebral, sense.

Things may be changing. AUT recently had a symposium on the nature of the printed image and South Island printmakers Barry Cleavin and Jason Greig came and exhibited in Auckland. On the other hand Muka workshop in Ponsonby winding up their international and national residencies (and are about to send their huge press south), and not many people seem even aware of the loss.

As a medium printmaking has a remarkable history of nourishing expressions of ridicule and moral indignation attacking human stupidity and cruelty.

‘Collateral damage’ is one of those black expressions that sprung out of the Vietnam war and served as a cold blooded euphemism for those civilian casualties that occurred as a result of attacking military targets. Michael Reed, a printmaker in Christchurch, has used the term in a title of one of his artworks and Elizabeth Rankin, an art historian based at Auckland University and curator of this show, has adapted it to make a thematic exhibition title. Though the heading also states social commentary, these works are not really about social observation. They are more hard hitting than that. They are motivated to bring about palpable change, to morally improve the behaviour of our species - not just stand back and watch.

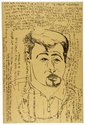

Possibly the most highly regarded historical figures in printmaking are Goya, Dix and Callot, famous for their methodical attacks on the barbarities of war. However the scope of this display is wider. Michael Reed’s target’s are principally arms dealers and their military clients. Sandra Thomson, another gifted printmaker from Christchurch, is preoccupied with the sexual abuse of children in the Catholic Church, while Diane Victor in her aquatints looks at the conditions of poverty and brutal conflict in South Africa. Daniel Heyman (an American living in Philadelphia) on the other hand draws portraits of torture victims at Abu Ghraib, using them to make drypoint etchings. He witnessed and recorded their verbal descriptions of their ordeals.

Yet this show is not only prints on paper. Much of it is textile. On the walls hanging drapes of patterned screenprinted fabric provide a spectacular component, as do taut horizontal ‘blood’ soaked bandages bearing texts, and printed t-shirts on hangers. On the floor in one central room are vitrines containing engraved cake servers and large medallions with ribbons; in another smaller space on a long table is a concertina folded book describing the consequences of land mines; in the largest gallery are two long woollen custom-made rugs, one exploiting a pun on ‘carpet bombing.’

Despite the horror of its content, this Gus Fisher show is beautifully presented. Rankin has an elegant sense of placement (particularly in aligning narrow rectangles) and knows how to shrewdly coordinate the works of four quite distinctly different individuals. The catalogue too works well. It is highly informative and well illustrated, with the curator’s writing detailed in its expounding of the various working processes and interpretation of the subtle or not-so-subtle imagery.

Although she believes the work ‘is not overburdened with polemic and didactic messages’, thinking that these artists ‘do not provide answers to the questions they raise’, only ‘reveal what they have discovered’, it is a tub-thumping ‘soap box’ sort of show, those ‘questions’ aimed at preaching to the converted. It is not likely to persuade any rare individual who enters the Gus Fisher with contrary opinions. Yet though finger-wagging with its swastikas, bombs, generals, skulls and vaginas, it is not irritating. It is too intricate and alluring with its many cross connections for that. The Gus Fisher has rarely looked so intriguing.

Interestingly, because I come from Christchurch and have followed the practices of printmakers like Thomson and Reed since the early eighties, I think the work they are doing now is the best they have ever done. They are on a roll. Years ago their work was much more inward, smaller, denser and private - but now it is more looking out into the world. And larger. The more ambitious scale brings a formal excitement and immediacy their earlier work lacked.

For me Diane Victor is the big discovery of this show, a fantastically hard hitting artist influenced by Goya, Picasso, Ron Cobb and others but with occasional comic strip margins and a twentieth century visual ethos added. Her eye for graphic detail and innovative composition is extraordinary, especially when bodily posture is used to declare an emotional state.

Daniel Heyman with his Ben Shahn style portraits and encircling texts of torture is less varied. The bearded male facial images seem quite quaint - as if from a fifties book jacket - but their calmness serves as an effective foil to the horror of the verbal descriptions that frame them.

Although the moral issues in Collateral might seem to be clear cut, the imagery is rich, densely abundant and sometimes (as in the case of Thomson) tangential in implication. It needs at least a couple of trips to extract all it’s got to offer.

John Hurrell

Advertising in this column

Advertising in this column Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

This Discussion has 0 comments.

Comment

Participate

Register to Participate.

Sign in

Sign in to an existing account.