John Hurrell – 4 October, 2011

Overall there was a vast quantity of important work to sift through. But it was the film component (though not translated) perhaps that made this exhibition an especially amazing opportunity, and the fact that the show's hefty catalogue was packed with detailed information normally hard to access for English speakers.

Brisbane

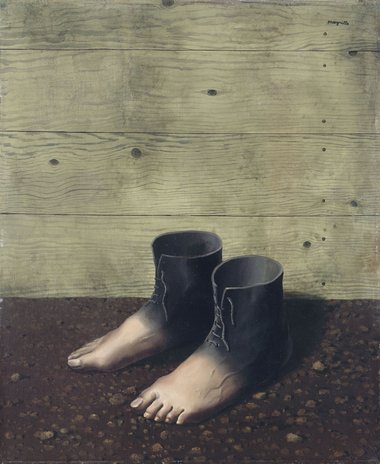

Surrealism: The Poetry of Dreams

Curated from the Pompidou Collection by Didier Ottinger

11 June - 2 October 2011

Surrealism has a key role in Australian art history that it mostly seems to lack in Aotearoa, except perhaps for its presence in Don Driver, the early work of Gordon Walters and maybe some of the Old Brain theories of Len Lye when he was living in London. The presence of important Australian surrealist painters like James Gleason and other artists like Nolan, Tucker, Klippel and Dupain who were briefly influenced when they were young, ensured the success of a great 1993 exhibition in Canberra that I was lucky enough to see, Surrealism: Revolution by Night.

Much of that came from New York collections, but this much larger, very thorough, even more sprawling show that has just finished in Brisbane came directly from the Pompidou and was assembled by Didier Ottinger, the Beaubourg’s deputy director, partially from the Breton archives. He saw the show politically as part of a sort of belated post-war countercharge that attempts to reassert France’s global cultural position in art after it got hijacked from Paris to New York. This regards Surrealism as still a presence in today’s art practice, especially contemporary installation. In Australia, Hany Armanious and Callum Morton might be good examples. Or Dan Arps and Julia Morison here.

Ottinger’s selection of 186 works from 54 artists was labyrinthine in its presentation, using a convoluted zigzagging floor plan to showcase painting, some sculpture, a lot of photography and collage, the magazines they published and a large amount of cinema - in curated screenings and on loops in the gallery space - as a means of expanding in its day new levels of consciousness and fertile imagination. It explored many areas within Surrealism’s history, such as its separation from Dada, Andre Breton’s various intellectual pursuits and his troubled relationship with the communist party. Breton as fractious ‘Pope’ and theoretician, intellectually dominated, quoted excerpts regularly lining the walls.

As in Canberra, Masson here was a central figure not often noticed by New Zealanders. He was very graphically influential on Pollock and Gorky and also in my opinion, on Phillip Clairmont’s colour sense.

In recent years the publication of Picabia’s collected writings (I am a Beautiful Monster, translated by Marc Lowenthal) has attracted much admiration. There are some great paintings by Picabia here and by his close friends Man Ray and Duchamp - and also important works by de Chirico and Dali. Yet an unusual Picabia-influenced Dali, a text that declares he is happy to spit upon his mother’s portrait (the words go across a woman’s outline, halo and the Virgin Mary’s heart) is a highlight because it genuinely surprises (‘shock’ would be excessive today, but not in 1929) having none of the ‘realistic’ visual conventions we normally associate with Dali.

This Brisbane show didn’t have the high hit rate of the Canberra event - which also included some great Australian work for there was a certain amount of dross, especially at its end (some weak late Massons, a few dreadful Brauners that made you wonder were they always bad or was it a matter of historical context?). Overall there was a vast quantity of important work to sift through. But it was the film component (though not translated) perhaps that made this exhibition an especially amazing opportunity, and the fact that the show’s hefty catalogue was packed with detailed information normally hard to access for English speakers.

One major point was its emphasizing the contribution of women previously downplayed such as Dora Maar, Claude Cahun and Dorothea Tanning - still vastly out numbered by men as creative personalities but their presence was much more accurately noted.

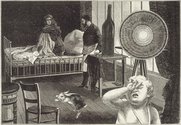

So looking at its film selection, Buñuel and Dali’s film Le Chien Anadou now seemed humorous as much as ruthlessly savage, with its anarchistic mockery of love for example, while Germaine Dulac’s The Sea Shell and the Clergyman (1926) with Artaud’s script, was a wonderfully constructed movie, beautifully lit with a mixture of tenderness and scorn for the adulterously motivated, smitten priest (too much sympathy - Artaud was enraged). The exhibition’s film component was surprisingly varied raging from Maya Deren’s At Land a social critique following on from Buñuel, to Eric Duvivier’s filmed variations on Max Ernst’s collage series La Femme 100 Têtes.

This survey was huge (and it had supplementary film screenings as well, plus online looks at publication archives), so to explore it properly took several ‘expeditions’. Locals working nearby consequently had a big advantage over out-of-town visitors, for they could dip in whenever they pleased. It’s all over now, but well worth snapping up a catalogue if you spot one in a book store.

John Hurrell

Advertising in this column

Advertising in this column Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

This Discussion has 0 comments.

Comment

Participate

Register to Participate.

Sign in

Sign in to an existing account.