John Hurrell – 4 April, 2012

What do you mean, we? is a surprisingly varied show, with far more nuance than you might anticipate. Although the conclusions about bigotry are understood right at the start, the methods of discussing its appearance or damaging consequences hold your attention.

Auckland

International group show

What do you mean, we?

Curated by Bruce E. Phillips

3 March - 6 May 2012

Review Part 2

The five artists of this discussion - presenting work in What do you mean, we? - look at racial prejudice as subject matter, a form of interpersonal hostility to be abhorred, eradicated, and puzzled over in terms of its origins.

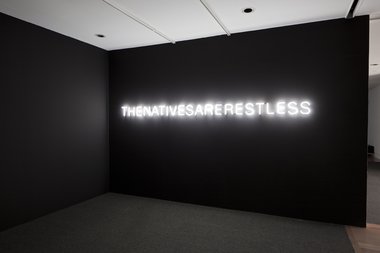

Australian artist Newell Harry’s neon sign, The natives are restless, mocks entrenched colonial values by deleting selected letters from the title phrase and using the remaining five to call the speakers ‘arses’. It nails them with the content of their own words while the blank gaps between letters become subtle ciphers that obscenely pun on ‘holes’.

Elizabeth Axtman contributes a video that shows a man handcopying a sample racist diatribe (out of two hundred) sent by a Philippino hate fanatic, David Tuason, to black men who had romantic relationships with white women. This letter, which the artist reads aloud, Tuason originally signed ‘Sincerely, All White Women’. After being arrested he pleaded guilty and sent to jail, and it was discovered his actions were sparked off by his own white girlfriend leaving him for a black lover.

Axtman then includes a letter she personally sent Tuason, signed ‘The Love Renegade’, where she urges him to replace hate with love, and learn to forgive not only those who betrayed him but himself. This work, about four minutes long, is oddly compelling in its compression of his despicable actions jammed up against the artist’s compassionate response. A female voice narrates Tuason’s letters while a male one reads out hers, this theatricality drawing you into the bizarre content.

The highlight of Phillips’ show is I think a video by Tom Johnson, an American artist who verbally improvises for half an hour about his own fears and self doubts over his curiosity about /insecurity with black men, picking at his childhood memories, dreams and daily thoughts about his regular job as a masseur.

Mixed in with this soul-searching is a certain amount of cunning in the way he positions his head to the camera and exploits his mournful eyes and whining nasal voice. Johnson is a clever storyteller with dramatic sound effects, arm and back movements. His work’s title, What a black man feels like, puns on emotional and physiological feeling as he attempts to dig around the nature of his interest in the textures and colours of black male bodies, not white ones - though he is interested in working on the bodies of white women. An engrossing, thoughtful, multi-layered work.

When I first saw the beautiful animated video by Rangituhia Hollis depicting dozens of hammerhead sharks swirling around in the skies over the suburb of Mangere, I was puzzled by its inclusion. I still am. The silver-grey fish, with beamed light streaming through them, seem to be restless ancestral totems, or local spirit guardians prowling around, always on the move.

The work is ambiguous. How are these streamlined fish to be interpreted? Do they protect and shelter, or are they fearsome predators, symbols of urban phenomena like gangs? They are open to a varied range of understandings. Perhaps they refer to destructive social phenomena like prejudice itself.

The artist collective, Boat-people.org focus on embarrassing the Australian government over its imprisonment of Indochinese asylum seekers, seemingly by using as a model for its public demonstrations, Magritte’s famous painting The Lovers. That 1928 work depicts a man and a woman kissing with their heads shrouded in cloth, and in their performances Boat-people.org organise groups at conspicuous tourist sites to cover their heads similarly with Australian flags. This is an act of solidarity that states Australia embraces all ethnicities. Hiding one’s face also implies shame.

What do you mean, we? is a surprisingly varied show, with far more nuance than you might anticipate. Although the conclusions about bigotry are understood right at the start, the methods of discussing its appearance or damaging consequences hold your attention. An important, immensely interesting exhibition.

John Hurrell

Recent Comments

John Hurrell

Kia ora Anna. That information is much appreciated. Bruce did provide some explanation in the hand-out, but in my case, ...

Anna White

The relevance of Rangituhia's work to the exhibition concept is explained by its title: Kia mate mango-pare. This is an ...

Advertising in this column

Advertising in this column Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

This Discussion has 2 comments.

Comment

Anna White, 12:26 a.m. 5 April, 2012 #

The relevance of Rangituhia's work to the exhibition concept is explained by its title: Kia mate mango-pare. This is an abbreviation of the whakatauki (proverb), "kia mate mango-pare, kei mate wheke (don't die like an octopus, die like a hammerhead shark). The whakatauki refers to the characteristic response of either animal when caught. Octopus are easily subdued; the shark puts up a fierce fight. In short, the artist is promoting Maori resistance to prejudice and the legacy of the colonial project.

John Hurrell, 7:34 a.m. 5 April, 2012 #

Kia ora Anna. That information is much appreciated. Bruce did provide some explanation in the hand-out, but in my case, the penny didn't drop.

Participate

Register to Participate.

Sign in

Sign in to an existing account.