John Hurrell – 3 April, 2012

I feel strangely schizoid because ultimately I don't think art can ever be interesting if it relies on viewer identification with a moral cause. Art to be really good has to be a lot more intriguing than that. Perhaps it can even be the opposite, going against the viewer's ethical inclinations whilst nevertheless being mesmerising through a fresh approach to imagery, ideas and semiotic juxtaposition.

Auckland

International group show

What do you mean, we?

Curated by Bruce E. Phillips

3 March - 6 May 2012

This exhibition which showcases ten artists’ or art groups’ attacks on the psychological phenomenon of prejudice, has for its title a clever reference to the old joke about The Lone Ranger and Tonto being surrounded by Apaches and The Lone Ranger asking Tonto, “What do we do now?” and Tonto replying “What do you mean,‘we’?”

It also tangentially alludes to some Maori intellectuals stated annoyance with being called ‘Kiwis’ or ‘New Zealanders’. The community of Maori within Aotearoa they perceive as making up that nation and separate from and distinct from those other (interchangeable) groups.

The curator Bruce Phillips’ title is also brilliant because it provides an ambiguous element of self critiquing. Prejudice is a tricky topic because in shows like this it is implied that there is such a thing as a normal or healthy sort of citizen who is free of this disease and who is generously represented in the art community. It is assumed that in the audience the reasonable, decent and fair people dominate and that they (ie. ‘we’) all agree. There very rarely is an interactive forum because the ‘bad guys’ are kept at arms’ length. They are never invited to the party because curators and directors are terrified of controversy or open displays of anger, and so a genuine exchange of views from opposite positions is impossible.

To give it a bit of manageable focus (and also to link up with the previous piece of writing around Luke Willis Thompson’s exhibition) I want to present this discussion in two parts, the work divided up according the type of prejudice discussed. One type is non racial, to do with gender, sexual preference, and class (employment status), the other is about ethnicity.

Kalisolaite Uhila is a NZ/Tongan artist who for this show was living for a fortnight as a homeless person in the Te Tuhi grounds, eating food donated by local visitors, sleeping under a cardboard shelter and old tent, and continually keeping his face hidden with a hood and scarf so he remains an ‘everyman’ - devoid of individual characteristics.

An unusual figure with his strange bulky clothes - feared and despised by many, even being spat at - Uhila shrewdly counteracted such hostility by creating chalk drawings for Te Tuhi’s brick walls, taped on photocopied images about unemployment and class structures, and signs out of cardboard with aphoristic messages. A few possessions were left in a supermarket trolley nearby. For those willing to look he became a personality, not a ‘thing’.

Uhila’s visibility was a catalyst for local debate about the homeless and the vulnerability of many New Zealanders to the government’s economic policies. I wondered about the ethics of his taking on such a role (he has a safety net with job and family) - for despite sincere and noble intentions it seemed insensitive to live in such a manner voluntarily. However I was also aware that such a project was physically dangerous. He could have been beaten up for his convictions; he’s courageous.

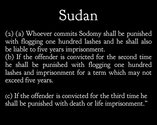

Colin Nairn’s contribution to What do you mean, we? is quite different in method: a series of chilling textual statements on a video presented in a Joseph Kosuth style (white letters on black field), quoting verbatim repressive homophobic legislation from the statutes of 79 countries. Though not particularly sophisticated structurally, it is intriguing if you are interested in legal terminology and old fashioned, amusingly vague, Biblical language where nothing about intimate physical acts is ever said directly or described. The illegal activities are stated obliquely, as if the activity of reading any detailed description might corrupt.

Another language-based work, but aural not visual, is Ayanah Moor’s 5 hour long All My Girlfriends, a work where captions from 25 years of swim suited gatefolds (1973 -1998) published by the magazine Jet are read out to show variations of adjective / name / measurements / home town / job / hobbies. The 1,296 descriptions of various black women gradually vary stylistically over time. Whilst attempting to convey something of their interests and daily lives, they also with inane adjectives try to feverishly excite the (presumed) male readers as a parallel to the seductive poses.

Simone Aaberg Kærn is a Danish artist who in 2002 flew her small single engined Piper Colt 6000 miles from Copenhagen to Kabul (over the Himalayas and dangerously violating military airspace) because she wanted to meet and encourage a young Afghani woman who wished to be a fighter pilot. Her 70 minute film is quite extraordinary with its images of austere aerial landscapes and the many people who help her, and the story is gripping as the tale about pioneer Middle Eastern women pilots unfolds. Kærn is driven in her attempts to help the Afghan but in the end patriarchal family values rule.

In Singapore during the Asian financial crisis of the late 90s, working conditions and job opportunities rapidly deteriorated for women and it became illegal to present performance art, especially on the streets. Amanda Heng’s four monitors show documentation of her illegally leading a group of mostly women in a Fluxuslike action, all walking backwards through the city (and later other cities in other countries) by using compact mirrors to look over their shoulders. Heng has a high heeled shoe jammed in her mouth, scornfully ridiculing male expectations of women to be constantly sexually alluring.

I personally like almost all the work in this exhibition and identify with the artists’ concerns and aims. It is a very inventive, engaging and informative show. Yet I feel strangely schizoid because ultimately I don’t think art can ever be interesting if it relies on viewer identification with a moral cause. (I say this, aware of my own privileged, very fortunate, background.) Art to be really good has to be a lot more intriguing than that. Perhaps it can even be the opposite, going against the viewer’s ethical inclinations whilst nevertheless being mesmerising through a fresh approach to imagery, ideas and semiotic juxtaposition. The really superb works don’t lean on viewer empathy to succeed; personal moral positions are irrelevant.

Tomorrow in Part 2, we move on to the rest of the show: racial prejudice.

John Hurrell

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects Advertising in this column

Advertising in this column

This Discussion has 0 comments.

Comment

Participate

Register to Participate.

Sign in

Sign in to an existing account.