Andre Hemer – 20 June, 2012

In Bass Principles Cairns allows us time to see, just as he has so clearly allowed himself time to make. At a time when such making and sincerity is often seen as uncool this show unapologetically suggests value in the slow burn.

Mitch Cairns’ exhibition Bass Principles is an unusually dainty affair. It’s overtly pretty, sensitive, and fastidious - none of which seem particularly central to the canon of contemporary art right now. The show shows the possibilities in setting up the simplest of constraints to paint by, and then beavering away - trusting in a process to develop a body of work.

The title Bass Principles is part play on words and part reference to a short course taken by Cairns at the Tom Bass Sculpture Studio School in 2011. At the same time he undertook a second course in the form of the Alan Moir Advanced Cartoon Classes - a ten part internet package. Both of these manifest themselves in his work: firstly as a seemingly a satirical gesture, and secondly as an embracing of the studio methodology of making a painting. Bass Principles is fundamentally the result of one artist locked in a studio and playing with a set of self-imposed formal and conceptual limitations. It’s difficult to make paintings that talk about painting while avoiding the ironic, but this is the territory that Cairns elects to navigate.

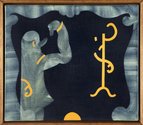

His work is of two types: eight paintings take up most of the main space, but a small selection of ‘cartoon’ RISO prints are also on one reserved wall. The aesthetic qualities of the painting allude to the clean curved lines of Art Nouveau and advertising mock-ups of the fifties. They also recall the rich figurative murals of modernist painter Stuart Davis and the iconography of some of Tony de Lautour’s recent paintings - particularly where the palettes are stripped back and his scribbled motifs made cleaner.

The difference between Cairns and de Lautour lies in Cairns’ economy. While de Lautour prefers to construct a magpie’s nest within a single painting, Cairns’ paintings are more passing vignettes that flow in and out of each other. Often the main motif of one painting is also found as a small element in another, creating a play of pictorial scales. Even in a show with so many potential narratives it isn’t necessary to go story hunting. Each work refreshingly embraces its own internal complexities.

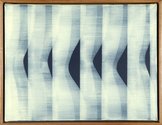

The exhibition’s visual focus is established by the creamy white optical tenacity of One half of a woman’s waistline repeated (study II). On both walls assorted motifs get repeated from painting to painting, jumping from the geometric stack of Bartender to the lyrical wanderings of Smokey Sad Square.

The most compelling painting here is Cigarette (thinking). Through the motif of a burning cigarette we are taken to the artist’s studio, briefly to indulge in the romanticism of the imagined process. It’s akin to a play performed with Greenbergian stage design but narrated through the music of electronic four to the floor. Its economy is gorgeous - thin, overlapping watered-down brush strokes rendering a cloud of swirling smoke and cigarette elements within a simple blue boundary. Restrained colour is also evident - the palette made up of navy blue and smatterings of deep mustard yellow. The intentionally muddied colour is the antithesis of any contemporary flavoured industrial or digitally saturated hues.

The most successful paintings seem to be the most efficient - both in making and in chosen iconography. This exposes therefore the more hesitant works. In Man Impersonating a hat stand for example, the layered brushwork and pictorial complexity seems overworked and less confident. However such slippages between works actually surprise the audience, giving them something to chew on. It’s a hang that gets better with repeated viewings.

The RISO-printed Cartoon works complete this show on a lighter, quirkier note. If the paintings describe the ontology of the studio environment, these other items describe the sociological reality where Cairns’ painting comes to reside. In Cartoon XIII a collector in the form of a talking smoking canvas asks ‘and who’s this?’ in response to what resembles a Cairns’ painting hanging on the wall. In comparison the other works in this series seem more esoteric and less self-effacing. They hold their own but are less memorable than the pictorially playful paintings.

Cairns’ embracing of and commitment to conventions is what makes this show memorable. Here is an artist willing to go backwards to go forwards. Certainly he is not the first to take this approach in recent times - one only need look at Tomma Abts and the resulting legion of art school graduates riffing on her geometric whimsy after she won the Turner Prize half a decade ago - but Cairns does things his way, his sensitive, motif-based language taking an even bigger risk at being written off as twee or uncritical.

In Bass Principles he allows us time to see, just as he has so clearly allowed himself time to make. At a time when such making and sincerity is often seen as uncool this show unapologetically suggests value in the slow burn. As artist David Ryan writes in his recent Art Monthly article ‘On Painting’, ‘Even with painting’s recent theorisation it is remarkable how it continues to be addressed simply as an object - almost as a token either within market economies, scenarios of globalisation, or caught in the fire of criss-crossing traditions, ideologies and allegiances. It is as though the time of making is still endlessly suppressed in any conception of painting.‘1.

Indeed painting is never static in this respect, for naturally it reflects a time, place, and culture. It also has the ability to inflect those same values. The current dominant paradigm seems to be a loose scrambling of ideas - purposefully slack with the steering wheel - the inevitable crash more interesting than any personal intent. In contrast, Cairns has his hands firmly grasping the wheel, navigating the roads from personal memory to a destination sentimental and known.

André Hemer

1. In David Ryan On Painting, p.11, Art Monthly, April 2002, no.355, London, Britannia Art Publications.

Recent Comments

André Hemer

And in a strictly painterly sense Korean artist Lee Ufan (From Point and From Line series) is probably the artist ...

André Hemer

There's certainly a similarity to those Persson works - there's a couple at the AGNSW that are somewhat visually related ...

John Hurrell

Is there a pinch of Steig Persson there, Andre - his calligraphic 'scroll' paintings from Melbourne in the mid-eighties?

Advertising in this column

Advertising in this column Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

This Discussion has 3 comments.

Comment

John Hurrell, 9:46 a.m. 20 June, 2012 #

Is there a pinch of Steig Persson there, Andre - his calligraphic 'scroll' paintings from Melbourne in the mid-eighties?

André Hemer, 10:26 p.m. 25 June, 2012 #

There's certainly a similarity to those Persson works - there's a couple at the AGNSW that are somewhat visually related through those calligraphic-like shapes. Agatha Gothe-Snape is a contemporary Sydney artist who relates somewhat - although the iconography in her painting/drawings are more abstracted/less introspective.

André Hemer, 10:35 p.m. 25 June, 2012 #

And in a strictly painterly sense Korean artist Lee Ufan (From Point and From Line series) is probably the artist that seems closest to Cairns.

Participate

Register to Participate.

Sign in

Sign in to an existing account.