John Hurrell – 21 November, 2012

I'm not sure if the data storage from the moving tools succeeds when replayed. Whether via the wall projection or the fibre optic brush-heads, the swirling and frenetic motion of these works is too busy to effectively convey the vectors of simulated brush/broom movement. The leap from chromatically agitated, vertically aligned bristle screen to horizontally planar floor space (as a correlated code) is not obvious, despite the intense illumination being extraordinarily eyecatching.

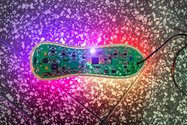

Eddie Clemens’ fibre optic broom sculptures are well known now, particularly the first variety of electronic bristle head he came up with, the ‘first generation’ works he developed in Dunedin and showed at Crockford’s and in group shows in spaces like St Paul St Gallery Three. I’ve fond memories of those works because of the unusually piercing intensity of the LED generated colour (they ultra-dazzled) - spread throughout the whole rectangular block of fibres - and the subtle transformations during the programmed sequences. Simple but nuanced.

Clemens’ newer version, seen in Wellington in The Obstinate Object, is more complicated. It features horizontally and vertically spreading, rippling movements and running texts and is a prominent feature in this Gus Fisher show. It’s an exhibition that deals - in a strangely detached way, for the bristles never touch the floor (nor is there soap or water) - with the politics of cleaning, a form of manual labour that normally remains invisible. In so doing, it references key conceptual art works by figures such as Joseph Beuys (Ausfegen, 1972/85), Billy Apple (Sweeping, Vacuuming, Mopping, Washing: Four activities [1971]) and Mierle Laderman Ukeles (Sidewalk: Washing Performance, 1974).

Those listed historic works were motivated by (respectively) notions of democratic participation, private and compulsive anxieties about cleanliness, and the status of women outside the then male dominated artworld, but Clemens seems chiefly driven by other concerns, such as his pleasure in inventively incorporating advanced electronic technology into mundane objects. That is natural enough, for there seems no limit to his wildly expansive imagination.

In Total Internal Reflection he uses two of the Gus Fisher galleries: the central courtyard with the domed ceiling, and the large rectangular room on the left of the gallery entrance. These spaces present four sculptural components: a broom hanging on a wall in the first; two similarly glowing scrubbing brushes on the floor, and a digitally animated wall projection of the interior of the first room, designed to look like a window that has dissolved the wall, in the second.

In the central space Clemens’ Second Generation broom, with its exposed ‘screen’ of ninety optic fibres, displays several types of information: firstly details about movement, direction and speed, acquired using embedded tracking mechanisms during a private ‘sweeping’ of that display room, data that has been stored in order to be transmuted and later replayed as moving coloured formations within the bank of fibres; secondly, the name of the cleaner, the time and place; thirdly, transformed data from an earlier sweeping in the SOFA gallery in Christchurch; fourthly, that Christchurch cleaner, time, and place.

Inside the rectangular gallery we see on the floor the two scrubbing brushes, positioned on their sides so that the bristles are exposed. One features a ‘cleaning’ in that room by Clemens himself, with four undulating blocks of colour (meeting at a vertical / horizontal intersection), the other features a text written by Andrew Clifford that is also published in a catalogue. The moving line of words is hard to keep up with and absorb, so in the end it is the hypnotic movement of the letters that becomes the subject matter.

Sometimes also the running texts and scrubbing motions of the handheld brushes seem to be combined in an attempt at disorder (a theme of Clemens’ show planned for the SOFA gallery in earthquake sensitive Christchurch) - mingling, changing alignment or suddenly reversing direction. This sense of spontaneous decision-making (or even anarchy) is extended from the scrubbing brushes to the projected digital image of eight brooms lying on the floor, their heads standing vertically on one end and all connected by a circle of handles. Colours can rotate or else jump back and forth, linking opposite sides.

The title of the exhibition refers to the internal properties of the each optic fibre, the light bouncing from side to side, and the reflexive nature of the Gus Fisher show itself with one room imaging the other.

I’m not sure if the data storage from the moving tools succeeds when replayed. Whether via the wall projection or the fibre optic brush-heads, the swirling and frenetic motion of these works is too busy to effectively convey the vectors of simulated brush/broom movement. The leap from chromatically agitated, vertically aligned bristle screen to horizontally planar floor space (as a correlated code) is not obvious, despite the intense illumination being extraordinarily eyecatching. As with a white hot magnesium flare, you can’t look away.

Clemens’ transforming of these hand tools through LEDs is clearly brilliant as a novel form of electronic noticeboard, but it doesn’t make conceptually rigorous social commentary on low status work like cleaning the way using genuine scrubbing brooms or brushes with elbow grease might do. It seems comparatively trivial. However if you ignore any artistic aspirations of being political, and want to enjoy this sculpture as a highly unusual optical experience, it is well worth a visit.

John Hurrell

Advertising in this column

Advertising in this column Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

This Discussion has 0 comments.

Comment

Participate

Register to Participate.

Sign in

Sign in to an existing account.