Megan Dunn – 1 November, 2012

Later, we travelled to Dunedin to do a group show at The Honeymoon Suite called with knowing pomposity 'The New Surrealism'. This time Graham exhibited the eggs outside in the gutter. Their white frilly edges faced the heavens and were illuminated by streetlights on long concrete stalks.

Graham McFelin was my first understanding of what a real artist might look like. He wore a maroon suit, had tousled stringy brown hair and a mischievous smile that he was in the habit of covering with his fingers. McFelin was the mastermind behind such cripplingly unknown works as: a portrait of the Alien from Communion, a small scrap of canvas camouflaged as an orange peel, and a ruffled brown paper bag, open at the neck, revealing mechanical laughter from within. He lived with his partner in a dark narrow house somewhere between Grey Lynn and Point Chevalier. I can still remember the sweep of Japanese Maple trees along their street, the dark red leaves dripping with rain at night, and the sky like a flat top pressing down on our heads.

Graham was the first (and only) person to ever tell me I walk like a crazy person. He included details, like the way I speed up or slow down, without any obvious physical impetus. After he mentioned this, I became aware he was right. In the late 90’s I was striding around Auckland to the music of my own mind, a chorus of thoughts clouding the fact that to an outside observer, I looked totally loopy. Graham was also the first person to suggest to me that all the artists who I saw as competition would one day be the people who’d shared the journey. He was near (or even over) forty when we met and now as I approach that hallowed age I’m aware that he was right. At the time I made appropriated art videos (Graham told me to work quickly because sooner or later someone else somewhere in the world would have the same idea) and I never suspected that I wouldn’t be able to sustain this practice over my adult life. It’s with a mixture of fondness, nostalgia and intrigue that I look back on this man, who still to this day is one of my favorite New Zealand artists.

The tattoos on his hands had faded to wobbly indistinct lines like those on an Etch-a-sketch. The rumors about his checkered past and misspent youth just provided more evidence of his integrity as an artist. I was twenty-three and in pursuit of excitement and bad behavior. Artists were people who had lived. Van Gogh cut off his own ear. No one could claim he was in a good mood when he did it. I was still at art school but hadn’t found the experience pleasurable or significant. The teachers there barely seemed to notice me and when I did gain their attention, it was only to be told to look up famous international artists in the Library. I had a crazy notion that art was actually happening here in New Zealand and I was going to find it. That’s why in my third year, I opened Fiat Lux, with my best friend, David Townsend. Suddenly we were in the business of discovering artists. (We didn’t have to look them up in the library.) We were scouting for talent and we found Graham McFelin.

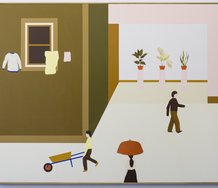

Now I do say this with some awareness of the absurdity. Of course we didn’t discover Graham, he was his own person, with a bundle more life experience than me. Yet I’m touching too on part of McFelin’s charm. He always seemed sprinkled with a little of the pixie dust that we attribute to ‘outsider artists.’ But this is a bit of a misnomer. McFelin had studied at Ilam and already moved through several phases in his practice. He was not an outsider, although his work trades in the eccentricity and ‘naivety’ we commonly associate with these figures. In Graham’s case much of this was an illusion, albeit a sincere one and his exhibitions were peppered with great visual pranks and puns.

McFelin’s first show at our new gallery was called Trick Eye. He’s the only artist I know who has ever exhibited an egg. Not a portrait or a photo of an egg. The egg itself, fried, over easy, served up in our window box so that Hobson Street could appreciate its yellow sunny eye.

Later, we travelled to Dunedin to do a group show at The Honeymoon Suite called with knowing pomposity The New Surrealism. This time Graham exhibited the eggs outside in the gutter. Their white frilly edges faced the heavens and were illuminated by streetlights on long concrete stalks. The eggs were as alien as the almond eyed stranger that graced the cover of Communion. This portrait hung in a corner of McFelin’s living room, the alien as mythical and mysterious as the Mona Lisa, casting its pallor over our world, changing the face of our future and our past.

In the gutter outside The Honeymoon Suite that night the fried eggs resembled flying saucers…

McFelin’s practice fits snugly inside the lexicon of curios; of and from the op shop, art that could no doubt slink back into a display at the Salvation Army and the hapless viewer would be none the wiser. Aaah, New Zealand, home of so many op shops! Think of St Kevin’s Arcade and the multitude of cafes and bars that still fetishize 60’s and 70’s decor. Our love of the second hand sits somewhere betwixt and between irony and adoration. Perhaps it even betrays a yearning to return to the false Eden of childhood, an era now imagined as simpler, or at least more stylish than it probably ever appeared at the time. And of course with better linoleum.

But there’s more than kitsch at stake in the art of Graham McFelin. The items that he selected to work with were humble, small scale, frequently domestic, even biodegradable, carrying connotations of social status and class. McFelin worked with these items on their own terms. He didn’t elevate the materials he selected, he moved them sideways: from the frying pan to Fiat Lux. McFelin’s art was over-easy: a blue t-shirt, proudly sprouting two rotund coconuts. Humour was high on the agenda. Not for us the po-faced sensibility of minimalism with its tight corners and hospital tucks. No, we wanted Graham’s Bag of Laughs. His Trick Eye. McFelin was an irreverent thrift store magician and a househusband, whose work seems to have snuck back into the suburban dreamtime it once crawled out of. Look closely. In your midst: Egg Fu.

McFelin brought art down to size and that was something I related to. He crafted a replica of an abstract Henry Moore sculpture out of yellow foam. This cheesy doppelganger was exhibited on a white plinth at Teststrip. A weight was submerged inside the foam. You could knock over the Henry Moore and it would bounce back up. Graham and I laughed about that one quite a bit.

Maybe I’m inadvertently making it sound like I was the only one who was really into Graham’s art. This simply isn’t true. McFelin was a coveted figure in the artist run scene of the time, widely revered for his endearing work.

On Cuckoo’s website:

‘We apologise for the lack of documentation of the McFelin show. It comprised a remarkable live version of an Archimboldo vegetable composite face, some cast latex paintings, birthday decorations and a trousered, shoed and socked leg protruding from the ceiling. We were so overcome we forgot to photograph it.’

Dylan Rainforth furthers this explanation in his Auckland roundup of Log 14: ‘Demonstrating humour and generosity, 7psi by Graeme McFelin took advantage of the show’s date to celebrate his partner Diane’s birthday: streamers, helium balloons, a banner and a cake mingled alongside more obvious art objects. Obvious, that is, if one accepts the wonders of Graham: a trouser-leg and shoe falling through the ceiling (Paul Simon: “one man’s ceiling is another man’s floor”), or a bowl of vegetables carefully arranged to suggest Archimboldo (though for me never quite congealing, like those damnable magic-eyes). Three wonky-ass small white canvases-sans-frames, upon close inspection turned out to be elaborate latex imposters complete with painted-on staples. 7psi refers to a pressure half that we enjoy at sea level, a lightness akin to sucking helium: a kind of giddiness where perhaps we don’t fall through the floor but float up through the ceiling.’

From Robert Hutchinson in Log Illustrated 2: ‘I’m not sure what to say about Graham McFelin’s show at Teststrip, except perhaps that the man is a genius. More mature than his Fiat Lux show last year (no strategically placed fried eggs this time) but still exploring a realm that I find frightening and fascinating.’

And from Alastair Crawford in The Physics Room Annual 3: ‘Graham McFelin’s stunningly outlandish art often suggests more with one gesture than seemingly more complex artworks, a strike in the memory that resurfaces for months. Also denying narrative, his twinked-out cigarette packet suggests a mistake that can’t be undone.’

Last but not least Tessa Laird in The Listener: ‘Another show that stood out for its mobility of meaning, if not its actual moving parts, was a group of eclectic installations by Graham McFelin collectively called Trick Eye. McFelin brought together such heart-achingly simple items as a fried egg, a paper bag and a five cent coin and made them art. Another highlight of the show was a bone with the name ‘David’ carved into it. I imagine this was a touching gift from the artist to the proprietors nose.’

Laird was right. This work was gifted to David Townsend, my partner in crime. The bone sat on a wooden doll sized dresser that had been painted bone marrow pink. The dresser was fixed to one wall of the gallery. It even had a tiny rectangular mirror, which reflected of course, the back of the bone. The work Graham gifted to me was a piece of rectangular leopard print cake tin. Attached to its surface was my name spelt out in colorful fridge magnets. I never knew quite what to make of this ‘portrait.’ It was an ode to the clothes I wore, more than to the depths of my soul. Or perhaps my soul just wasn’t quite as deep as I wanted it to be. (4 litres: the bladder of a cask of cheap wine.) In those days the cask wine flowed pretty freely…

Another mini McFelin collage from Trick Eye consisted of a black and white print of a man’s face, folded into a work of 3-Dimensions and inserted inside a clear plastic box. This paper stranger peered out thoughtfully from his makeshift house. His pupils sharp as tacks.

McFelin’s last Fiat Lux exhibition was upstairs at St Kevin’s Arcade, our final location. It included a series of paintings that looked like they could have been salvaged from op shops. Imagine if the fauves had done fugly. If Rothko had of worked on the budget of a fiver. The paintings were abstract, camouflaged as naïve, but in fact highly controlled in their splurge of colour and splat of line. They were of a modest size, neither big nor small. McFelin’s paintings would fit well on the walls of most Grey Lynn flats.

Since returning to New Zealand, I’ve seen a lot of faintly grubby abstraction on the menu. At Artspace’s exhibition Caraway Downs I appreciated a painting that featured a folded Chux cloth. Of course it reminded me of McFelin. And in some peculiar way the colour palette in Nichola Farquhar’s Hopkinson Cundy exhibition also reminded me of Graham. Nick Austin is a more obvious kindred spirit. In Notebook of a Spider I admired the audacity of Austin’s mixed media work in which a florescent light bulb hangs in front of a black painting. The glow of the bulb - its eggy halo - has been painted onto the canvas: that’s the punch line. Like Coughing’ Coffin or Bag of Laughs this artwork risks being swallowed whole by its gimmick. Austin too has a penchant for socks expressed in his painting Ghosts, a strange fusion of pathos and the pathetic. The empty sock is such a potent visual symbol for a male artist to play with. Now, I’m sure none of these painters, including Austin, are aware of McFelin’s work, naturally there’s a whole set of references we can concertina out of any artist’s practice. But still I spy with my trick eye. Who can predict when the zeitgeist will strike? Not everyone is lucky.

Perhaps it’s apt that McFelin’s work has not been canonized?

In an op shop in Kilbernie last year I chanced upon an entire cabinet of novelty salt and peppershakers. I was enjoying looking at this fetching collection, until the shopkeeper told me their original owner, an elderly lady, had just been relocated to a rest home. When Lot’s wife looked back over her shoulder she was turned into a pillar of salt.

There’s a trap door in my mind that opens and inside it is an artwork disguised as an orange peel. That’s the twist. In the work of Graham McFelin life isn’t still. It’s just moving slowly.

Afterword:

I wrote the majority of this essay remembering Graham McFelin’s work from exhibitions I saw approximately fifteen years ago. Thanks must go to Graham McFelin and Diane Miller who have since provided the photographs of his art and generously agreed for this piece to be published.

Megan Dunn

Recent Comments

John Hurrell

I remember Graham from his pre-Fiat Lux life in Christchurch. He and Grant Lingard, and Diane Miller too, had some ...

Advertising in this column

Advertising in this column Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

This Discussion has 1 comment.

Comment

John Hurrell, 10:04 a.m. 1 November, 2012 #

I remember Graham from his pre-Fiat Lux life in Christchurch. He and Grant Lingard, and Diane Miller too, had some terrific shows in the mid 80s at the James Paul gallery, a venue which provided the first real competition for the then dominant dealer gallery, the Brooke/Gifford.

Participate

Register to Participate.

Sign in

Sign in to an existing account.