Warren Feeney – 16 January, 2013

Parekowhai's two bronze bulls atop pianos placed among the ruin of the inner city made absolute sense as a metaphor for nature run rampant. On First Looking..gave expression to something about Christchurch that words had previously failed to encompass. It connected with the local community in a way that it is difficult to find a comparable precedent for in Christchurch's history.

Christchurch in retrospect

In Christchurch in 2012 it often seemed as though the arts were everywhere - except in the spaces of an art gallery; on the walls of buildings, in temporary make-shift spaces (reconstructed offices and houses), on sites recently demolished and cleared of rubble, online, as giveaway brochures, in the windows of heritage buildings about to be knocked down and on the streets of the inner city.

The positives were that in spite of the continued absence of a more familiar arts infrastructure, necessity did prove to be the mother of invention. New opportunities were revealed for exhibitions and installations, allowing the arts to assume a welcome visibility beyond the white cube of the gallery space in a city that, for most of its history, has demonstrated little tolerance for art in public spaces. The downside was an uncomfortable degree of uncertainty as temporary - and what were often assumed to be permanent venues and projects - came and went. In 2013, no one should underestimate the ongoing fallout from the lack of spaces and venues in Christchurch. Immediately apparent in the demands for accommodation throughout the city, this also continues to represent a serious challenge for all involved in the arts, but particularly artists facing a shortage of studio and gallery spaces.

In 2012, artist-run space, ABC Gallery on Lincoln Road was the first victim. Established in 2011 by Matt Akehurst, Zhonghao Chen, Oscar Enberg and Sebastian Warne, ABC’s galleries and studios closed in February. A change in ownership saw the demolition of the building and the development of more offices and café culture in Addington. Its absence was felt immediately, not least because the gallery closed, but also due to the departure from Christchurch of a number of the artists in its studios.

Its closure made the opening in June of the artists’ project space, Dog Park, and the support that accompanied it from Creative New Zealand, all the more welcome. Established by curator Chloe Geoghegan with Ella Sutherland, and later joined by lecturer in Art History at the University of Canterbury, Dr. Barbara Garrie, it has embraced the fine arts in the broadest sense, including an interactive editing and publishing of Matt Galloway’s The Silver Bulletin, in an edition conceived and realised in the gallery in early August.

Dog Park signified one further example of the commitment that Creative New Zealand has made since 22 February 2011 to ensure that an arts infrastructure is nurtured, artists remain in Christchurch and that the contribution that the city makes to the arts continues to exist. As the target of misguided criticisms following the February earthquake, CNZ’s advocacy and contribution has made a difference. To date, CNZ has contributed $1.9 million towards a range of projects; relocating artists into studio spaces, supporting new initiatives like Dog Park, Art Box, the Christchurch Art Gallery’s Outer Spaces projects, Gapfiller and much more.

Throughout the year, Jonathan Smart Gallery again operated a business-as-usual model with a programme of sustained quality. Looking at the line up of exhibitions in his temporary gallery space in sculptor Neil Dawson’s studio in Linwood, (for example; Saskia Leek, John Pule, Heather Straka, Lonnie Hutchinson and Miranda Parkes), the Jonathan Smart Gallery, all too modestly worked on the premise that exhibitions would be curated and take place regardless of circumstances. Smart opened the year with Dense Hang, a group show that established a context for the programme to follow. Work by artists such as Peter Wheeler, Fiona Pardington, Stephen Bambury and Rob Hood genuinely surprised, introducing the gallery visitor to little known or new aspects of each artist’s practice.

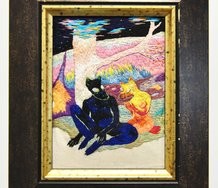

There was however, no contest for the highlight of 2012. It was Michael Parekowhai‘s On First looking into Chapman’s Homer from the Christchurch Art Gallery’s Outer Spaces programme. Located in temporary premises upstairs at 212 Madras Street and on an adjacent vacant site across the road, On First Looking into Chapman’s Homer, returned from the Venice Biennale, opening in late June and establishing an unexpectedly powerful and relevant - yet also entirely romantic - relationship with the public. The two bronze bulls atop pianos (Chapman’s Homer, and A Peak in Darien) placed among the ruin of the inner city made absolute sense as a metaphor for nature run rampant. On First Looking gave expression to something about Christchurch that words had previously failed to encompass. It may have simply been the place and time, but it connected with the local community in a way that it is difficult to find a comparable precedent for in Christchurch’s history.

The Christchurch Art Gallery’s Outer Spaces programme was equally welcome because gallery staff acknowledged that the city was now a different place. Sadly, the public gallery was going to be closed for some time. Changing shows every four weeks in the Madras Street space - this must be unheard of for any New Zealand public gallery - Outer Spaces set a precedent that it would be great to see continue when Montreal Street finally reopens.

Outer Spaces featured a number of exhibitions that also worked because of the way in which this temporary space was continually transformed. In August, a group show, Out of Place, presented works by Katherine Jaeger, Chris Pole, Tim J. Veling and Charlotte Watson. All considered the constructed environment anew. Watson’s reconfiguration of the office space used by gallery staff was particularly impressive. Acting as installation, environment and sculpture, she assembled erroneous shelfing, tables and chairs that brought to life the spatial complexities and contradictions of an analytical cubist painting.

The question mark in the title of Scott Flanagan‘s Do You Remember me Like I Do? in September was particularly pertinent. Gathering black video tape like a lake in the middle of the room, it implied that it might be alluding to the presence of memories. Yet Flanagan’s installation transcended the premise that this was simply a work about personal loss. Haunting in its impact, the gallery visitor found themselves looking into a void, uncomfortably aware that there was nothing staring back.

Of course, Outer Spaces also had another life as public art works. The most successful remains Wayne Youle’s I Seem to Have Temporarily Lost my Sense of Humour. Completed in December 2011, this large-scale public mural on the corner of Colombo and Byron Streets remains animated and engaging each time it is seen. Other large-scale works on walls varied more in their ability to connect with community. Kay Rosen’s Here are the People and There is the Steeple works best as a large and attractive wall of geometric yellow and black shapes, bringing spirit and energy to a vacant grey site visible from Durham Street. Yet, it also seems like it is sharing a private joke in public in an uncomfortable way that too willingly paraded its punch line.

Also currently vying for attention is Ash Keating’s Concrete Propositions, a massive work of art that must occupy half of the space between Gloucester and Worcester Streets. Firing paint onto a concrete wall, Keating has assembled a spattered and dribbled Jackson-Pollock-abstract-expressionist mural that up close is an object of great energy and beauty. Yet the experience is also one that may have been more suitably viewed in an art gallery space. Viewed from a distance Concrete Propositions was up against some serious competition from the surrounding demolition site: The adjacent building with earthquake damage cracks across its entire surface, plus the uninterrupted view from Madras to Manchester Street.

Making the most of the city as demolition site, and anticipating the possibilities for the arts in such circumstances, Measure the City with the Body, curated by the former director of The Physics Room Stephen Cleland, was an appropriate choice for its temporary site in Sydenham. Featuring video and film of performance and installations by Claire Fontaine, Daniel Malone, Junebum Park, Mark Wallinger, Pak Sheung Chuen, William Hsu and Yuk King Tan, it was a project that drew attention to the potential of the arts to engage with the public beyond the gallery. Even the placement of temporary sites on vacant spaces close to The Physics Room seemed to be in on the act. Using a series of freight containers as galleries for video works, the visitor’s attention was captured and sustained until they stepped back outside on to the empty sites, each time confronted with the context in which this programme offered new possibilities for the experience of art.

Artworks installed by SCAPE’s public art programme in December appear as though they have taken up the spirit of Cleland’s challenge. Both Joanna Langford‘s The High Country and Mexican artist Héctor Zamora’s Muegano are large works that possess a welcome and visible public presence. Both should have been part of the SCAPE’s 6th biennial project, yet their current exhibition in the city is no less impressive, with or without the wider context of a bi-annual arts event. Langford’s The High Country is sited 10 metres above ground on the corner of Montreal and Kilmore Streets. Constructed from recycled materials it appears like an apologetic utopian city - has Langford ever conceived and realised such a mature, entertaining or intelligent work? Lit up day and night it looks like an unused prop from a 1930s Sci-fi movie like H G. Wells’ The Shape of Things To Come. However, its humour and location opposite the now-demolished Cramner Courts also offers warm and poignant commentary on the folly of the ambitions of human behaviour.

In 2012, Director of The National, Caroline Billing offered an exhibition programme in which objects and ideas seemed perfectly integrated. In February, The National presented The Possession Obsession of Cocoa Vitako, new works by jeweller Octavia Cook, exhibiting under an anagram of her name in which her work become the subject of a show that critiqued its reason for being considered worthy of attention, alongside complementary images from pseudo-fashion magazines. Like the majority of exhibitions The National held, Possession Obsession represented a conversation with a known audience - those who admired, purchased and wore the objects on display - and it spoke to its fan-base in a disarmingly clever and unpretentious way.

The Ilam School of Fine Arts Gallery continued to make good use of one of the city’s best exhibition gallery spaces still intact and typically, exhibitions by Fatu Feu’u, Tony de Lautour and Select, works by graduates and post-graduates were all characterised by a restraint and elegance in installation. This worked particularly well for de Lautour’s exhibition early in 2012, in which he acknowledged the work of Kasimir Malevich and did so based on the premise that less was definitely more.

So does all this activity; exhibitions, installations and public art works seem like reassurance that the arts are in increasingly good heart in Christchurch? It would be misleading to entirely assume that this is the reality. The city continues to feel like two steps forward and one or more steps back. Just this week, I met with a local artist, four weeks away from leaving the city for better territory. She had already relocated twice since 22 February 2011 from a studio in the Arts Centre to rented accommodation she had converted into a studio, gallery and home, exhibiting her work and other artists on a regular basis. However, all has suddenly changed. Rapidly increasing rents, (flamed by insurance payouts for temporary accommodation to home owners needing short-term leases while their own home are repaired), now see her facing overheads that have put her out of her premises and business. She leaves after more than 20 years of working as a professional artist in Christchurch.

Adapting to changing circumstances and recognising that the temporary or transitional has its own distinct merits and rewards are concepts worth holding on to and cultivating in Christchurch. The Social, a public arts programme of interventions, temporary and transitional sculpture, performance and installation, instigated by the University of Canterbury School of Fine Arts technician and artist Gaby Montejo has sought to make a virtue of such circumstances. Coordinated by artist Lucy Matthews, The Social consists of proposals from local artists, implemented from November and run on a weekly basis until the end of February 2013 in the ReStart retail precinct in Cashel Street. Often seeking community participation, it has included projects like The Loss Adjustors, curated by Blue Oyster director, Jamie Hanton and Alex Lovell-Smith. The Loss Adjustors satirised the EQC claims process, offering those making a claim the appropriate form transformed into a work of art. Set up within 2½ months, The Social acts as a model for future transitional arts projects; initiated by artists, artworks and performances that take place outside familiar venues, a reconsideration of how the arts connects with communities and increased public visibility and participation in the arts by the wider community.

The Social also side-steps the premise of the arts talking exclusively to an arts-literate audience. At last, an arts initiative for Christchurch that it is possible to claim represents an appropriate way forward for the foreseeable future and whose potential has only just begun to surface. The Social is an arts project that is as affirmative for the artists participating as it is for arts audiences and the wider community. It represents the kind of democratic shift in normalising a community’s experiencing of the arts that I would trust Christchurch will remain keen to retain. In doing so, it will be a unique public arts project in the city’s history; one that is embraced as being important to the wellbeing of all its residents well into the future.

Warren Feeney

Recent Comments

Ralph Paine

All quantitative and all good, your comment reads like a report destined for some Creative NZ meeting. Trouble is there’s ...

Warren Feeney

You are overstating my intentions in commenting on the Christchurch community's response to On First Looking. It was an observation ...

Ralph Paine

No, in my view (as per the above) what Mr Parekowhai presents us with is a travesty, a farce. Whether ...

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects Advertising in this column

Advertising in this column

This Discussion has 8 comments.

Comment

Ralph Paine, 1:58 p.m. 17 January, 2013 #

Wouldn't to naturalise the quake be to normalise it; to make it seem as if the How? Why? and Where? of building cities had nothing to do with the event?

And yet how else but via such a naturalised, business-as-usual mind set could Mr Parekowhai's Merrill Lynch bulls atop pianos appear as anything but heroic and grandly historical?

Bring the How? Why? and Where? back in and all we see is Bi-Cultural Kapitalist Kitsch.

Warren Feeney, 9:57 p.m. 17 January, 2013 #

Hi Ralph

I take your point about the heroic and grandly historical state of Parekowhai’s On First Looking in Christchurch. Was it an easy and quick romantic fix, one in which the image of a city in ruin and the Bulls atop the pianos shared the same territory as the paintings of Delacroix, a battle scene from an X-men movie, Picasso’s Guernica or a Warner Brothers Looney Tunes cartoon? All belong to an iconography that relies on a well-worn grab-bag of popular images. Did On First Looking manage to rise above these – and did it need to? Sometimes restraint and subtlety are ideal for a work of art and on other occasions the heroic and full blown romantic and grand, works much better. (Christchurch still looks like a war zone – big, loud and obvious does have its role in seeking and commanding attention in such an environment). It depends on the time, place and intention. Having worried about whether or not I was being won over by an artwork that paraded its art historical and popular culture credentials, (and I did feel concerned about this), I felt that essentially there were many good reasons to confirm that in Madras Street in Christchurch in June 2012 Parekowhai’s On First Looking, deservedly had its moment, capturing the attention of the local community and offering them a way to make some sort of sense, or at least feel momentarily reconciled with the circumstances they were in. At its most fundamental, it might have just been that it was great to be able to have a good reason to go back into the inner city – the majority of it is still shut down and has been for more than 18 months. In regards to this work and the How? Why? and Where? Of building cities - It is these questions that in so many ways have been occupying the entire city’s thoughts and time for the past 18 months. Works of art have a role in all of this and from my perspective Parekowhai’s On First Looking has already made its contribution.

Ralph Paine, 2:38 p.m. 18 January, 2013 #

After summering-over in the cool, post-Duchampian airs of art touristy Europe, the hybrid thing arrives, plonking itself down right in the desolate heart of the ruined city. All buffed up and muscular, it is said that the hybrid thing has come to console through transcendence, to lift spirits above and beyond the wrecked lives, security fences, empty lots and rubble, so that they may soar for one briefly plucked moment in the sublime light of....

What a travesty, a farce – and yes, a grand one – and so I remain perplexed Warren as to why you didn't run with your initial gut instincts: they were right! Perhaps there was too strong a desire to speak the perceived voice of a community? To speak the romantic requirement of collective affirmation through aestheticised forms of time-out?

Trouble is, I for one can’t get past the hybrid thing’s in situ, social realist formula:

piano > platform > neoliberal iwi-state > market > bull > Merrill Lynch > financial capital > cycles of creation & destruction > war > business-as-usual > nature

In other words, What a downer!

Warren Feeney, 12:52 p.m. 19 January, 2013 #

So this was a condescending gesture towards the residents of Christchurch? I really cannot agree that this was the reality. The numerous publications on ‘Christchurch as it was’ that have hit the book stands throughout the city over the past 12 months are a travesty – shamelessly playing to nostalgia and sentiment but On First Looking was something quite different – firmly fixed in the here and now, directing visitors’ attention to both itself and the current state of the city. (And maybe accepting and dealing with that reality?) Being in Christchurch it becomes evident very quickly that the theory of Maslow’s hierarchy of needs – working our way up from food/shelter to the arts and self-realisation - is a complete fiction. Whatever our circumstances, we all seek security, community, and emotional and intellectual well-being simultaneously. Take a look at the photograph of the launch of Joanna Langford’s The High Country in this review and Maslow’s hierarchy of needs is revealed to be entirely egalitarian. A group of people gather on a decimated inner-city site (uninhabitable for any practical purpose) for a community gathering; tents, a barbeque, a portaloo and a work of art. To claim that the experience of On First Looking was an aesthetic form of time-out trivialises the response to it as sited on Madras Street.

Ralph Paine, 6:18 p.m. 21 January, 2013 #

No, in my view (as per the above) what Mr Parekowhai presents us with is a travesty, a farce. Whether or not the “residents of Christchurch” (or for that matter the residents of any place whatever) feel the same, and/or feel that this presentation is of a condescending nature, is not really my or anyone else’s call. In fact, right now ‘the residents of Christchurch’ is an in no way reliable working concept, and nor are ‘the public’ or ‘the local community’. Wouldn’t it be more helpful to talk of the coming community, the impossibility of residency, or of group-subjects rather than the public? In any case, what seems to me the condescending gesture in all this is your unwavering determination to speak in a manner representative of a community that, despite being impossible to get any concrete grip of, you wilfully and somewhat perversely imagine into existence. Take a look, if you will, at an example:

“The two bronze bulls atop pianos (Chapman’s Homer, and A Peak in Darien) placed among the ruin of the inner city made absolute sense as a metaphor for nature run rampant. On First Looking gave expression to something about Christchurch that words had previously failed to encompass. It may have simply been the place and time, but it connected with the local community in a way that it is difficult to find a comparable precedent for in Christchurch’s history”.

This would have to be one of the more condescending passages of text I’ve read in a very long time. Not only do you assume here the right to speak on behalf of some unexplained “local community”; you also insist on using this voice to assert extremely aggressive claims over both nature and history.

I do agree, however, that a flat ontology is the way to go: as you say, there is no place here for any hierarchy of needs, no need to conceive of art as being a concern for some later date. After all, the making of food, clothing, and shelter are all traditional arts. But there’s also the problem of art’s autonomy to consider, its validated time-out status as it were; a problem perhaps best encompassed by tensions operative today between (and within) the studio-gallery-museum nexus and the art-as-social practice/relational aesthetics nexus.

Ralph Paine, 11:03 a.m. 19 January, 2013 #

On looking again at the image of this version of Mr Parekowhai’s sculpture I notice that the carved elements have been removed, and thus the above formula is somewhat out of sync: rather than any neoliberal iwi-state platform, perhaps what we have here is piano as symbol of European settlement (see Jane Campion’s “The Piano”).

Apologies for any confusion caused.

Warren Feeney, 7:21 p.m. 22 January, 2013 #

You are overstating my intentions in commenting on the Christchurch community's response to On First Looking. It was an observation based on fact and personal experience; over the period of this exhibition/installation an estimated 66,000 people stopped at the Madras St site or visited the gallery, it was sited on one of only 4 routes available through the inner city with a relatively high traffic flow, its reception received significant and repeated coverage in The Press, (front page of the paper and a follow up),and on National Radio, as well as a column in Arts News.

Regardless of whether this work can be regarded as a 'travesty' once it arrived in Christchurch it assumed a life of its own that could not have been anticipated by the artist or those planning the Venice Biennale. It reminded me of the surprising response to Neil Dawson's Chalice in 2000. The subject of numerous public criticism and abuse prior to being sited in the Square in Christchurch, it's presence, immediately following September 11, for some reason transformed it momentarily into an object for remembrance of those who had died. For many days visitors to the Square placed flowers around it. Entirely spontaneous and evidence that, like On First Looking, public works of art, depending on time and place are capable of establishing relationships with the wider community that are meaningful, operating outside and beyond the agendas of the art world and the artist’s intentions or expectations.

Ralph Paine, 1:41 p.m. 24 January, 2013 #

All quantitative and all good, your comment reads like a report destined for some Creative NZ meeting. Trouble is there’s a big difference between a crowd and a community. And a big difference between an operative community and an imagined one: newspapers, radio, etc. are often destructive of operative communities, yet very creative when it comes to imagined ones.

Anyhow, if today's spectators always find themselves in a crowd, a crowd that has become more and more abstract and difficult to comprehend, then is it the critic’s role to somehow represent this crowd? If so, then major difficulties arise: e.g. how to differentiate between the crowd lining up to buy photos of pre-quake Christchurch and the crowd who visited Chapman’s Homer, and A Peak in Darien?

Yes,(public) art does connect with spectators in ‘meaningful’ ways unanticipated by artists, dealers, curators, administrators, publicity & marketing types, politicians, whoever.... It’s the hows, whys & wherefores of these connections that are important; the coded, symbolic, semiotic, and affective dimensions of these unexpected relations that need to be explored, not simply their raw data matter of fact-ness.

Participate

Register to Participate.

Sign in

Sign in to an existing account.