John Hurrell – 15 January, 2013

Despite Mitchell's prolonged investigations into dematerialization the book (like his shows) is highly sensual: gorgeous looking - with its Kleinian blue hard cover, saturated red endpapers, sections of pertinently coloured pages, carefully ordered glossy photographs, and meticulously detailed lists (using elegant typography) of presented works. The contents include not only the New Zealand shows but their Berlin precursor, Mitchell's Minor Optics exhibition at DAAD.

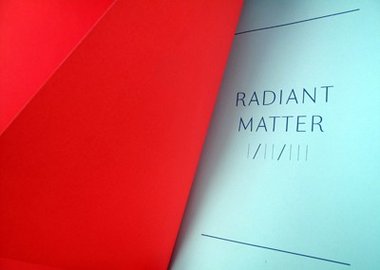

Dane Mitchell: Radiant Matter I/II/III

Essays by Ariane Beyn, Aaron Kreisler, Cay Sophie Rabinowitz, Chris Sharp and Dane Mitchell

Editor: Dane Mitchell

Designer: Tana Mitchell

Hardcover, 96 pp, text with colour illustrations

Published by Berliner Kunstlerprogramm/DAAD, in partnership with Govett-Brewster Art Gallery, Dunedin Public Art Gallery, and Artspace, 2011.

Dane Mitchell‘s show Radiant Matter was a particularly popular exhibition of 2011. Many artists I spoke to last year expressed astonishment that his project - with its three separate versions in New Plymouth, Dunedin and Auckland - was not included in the recent Walters Prize. Highly regarded, his name came up regularly. So here is the publication. (One that is downloadable.)

Despite Mitchell’s prolonged investigations into dematerialization the book (like his shows) is highly sensual: gorgeous looking - with its Kleinian blue hard cover, saturated red endpapers, sections of pertinently coloured pages, carefully ordered glossy photographs, and meticulously detailed lists (using elegant typography) of presented works. The contents include not only the New Zealand shows but their Berlin precursor, Mitchell’s Minor Optics exhibition made in 2009 during his residency at DAAD. The structure has the DAAD director Ariane Beyn discuss Minor Optics in the foreword, Aaron Kreisler separately elaborate on the three individual versions of Radiant Matter, and for each of those three, extra essays by Cay Sophie Rabinowitz, Chris Sharp and Dane Mitchell.

The German works, partially further developed later for the three New Zealand shows, consist of highly polished electrostatically charged metal plates that accumulate institutional dust, and the creation of a scent with French perfumer, Michael Roudnitska, synthetically replicating the smell of an empty gallery.

In Radiant Matter I (Govett-Brewster Art Gallery) there were works looking at the containment, condensation and dispersal of aroma, ozone and moisture ; in Radiant Matter II (Dunedin Public Art Gallery) the work contained occult energies, ancestral soil, dusty aromas, in obsidian surfaces - paranormal presences, and in pipettes - breath bearing spoken Mitchell’s ancestral names and (separately) bagpipe music ; in Radiant Matter III (Artspace) scent was (i) sprayed onto paper and presented behind 16 panes of glass under a controlled light spectrum (no green or blue that would break down the scent, leaving only red), (ii) circulated with a vaporiser, or(iii) presented in liquid form in pipettes on a mirrored (dematerialised) table.

Due to the cross-referencing in the writing the use of the red page-marker ribbon and list of works is essential to follow the discussion, for the writers don’t limit their content to the exhibition they are presented under. And although Aaron Kreisler is a skilled communicator the real writing stars here are Chris Sharp and Cay Sophie Rabinowitz, Sharp for his spot-lighting of the relevance of Duchamp and Klein, Rabinowitz for her incorporation of the atomistic ideas of the Epicurian Roman poet and philosopher Lucretius and, more obviously, Hans Haacke’s Condensation Cube.

Chris Sharp’s comparatively long essay ‘Trajectories of Immateriality’ starts with a fascinating quote from T.E. Lawrence about being shown the ruins of an ancient Arabian palace where perfumed oils were mixed with clay in the building’s construction, and (according to his guides) still detectable hundreds of years later. Sharp then discusses the history of the term Radiant Matter as a category of substance beyond solid, gas and liquid, discussing the research of nineteenth century scientists like Michael Faraday and William Crookes and how the term evolved to ‘plasma’, a fluid, formless material - neither gas or liquid - that needs to be enclosed and which conducts electricity.

He then draws out apt connections between Mitchell’s sculpture and the legacies of Duchamp (particularly works like 50 cc of Parisian Air, Mists on Polished Surfaces (Glass, Brass) and his concept infra-mince (ultra-tiny or almost-insubstantial)), Yves Klein (Zones of Immaterial Pictorial Sensibility) and Robert Barry (Inert Gases Series, and works which examine the limits of thought like Marcuse Piece and All the Things I Know but of which I Am Not At the Moment Thinking 1:36 pm; June 15,1969). Sharp is a supple thinker and clear writer, so this text is a great lead-in to mentally contextualising Mitchell.

In Cay Sophie Rabinowitz’s shorter ‘De Rerum Natura‘ she elaborates via an initial discussion of Lucretius on how Mitchell’s ideas relate, particularly concerning molecular particles moving through many permutations of transformative (but permanent) matter. These in Mitchell‘s corpus can be items of thought, feeling, ghosts, dust, sound in breath, ozone, spells, and more. If you coordinate Rabinovitz’s focus with something Chris Sharp points out - an observation by Yve Alain Bois that one essential condition of modern art is an awareness of the risk of being called a fraud, of being ridiculed, and that authentic work confronts, challenges, even solicits this possibility - the resulting blending makes a lot of sense.

Rabinowitz admires the hybridity of Mitchell‘s work, his conceptual amalgams of sculpture with photography, physics, perfumery, reflection, painting, and mental speculation - especially the transitional, transformative, Lucretian processes embodied, their unstable and protean nature. Mitchell’s own ‘Table of Elements’ consists of four apparently blank pages, with one and a half pages of footnotes. Rabinowitz points out that to read the ‘essay’ might involve invisible ink or require black light.

Though you can read the texts and scrutinise the images above, online, this book is a wonderful object to hold - it’s pleasurable to feel its textures, thicknesses and edges, bear its weight, sense its planar resistances. Well worth owning.

John Hurrell

Advertising in this column

Advertising in this column Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

This Discussion has 0 comments.

Comment

Participate

Register to Participate.

Sign in

Sign in to an existing account.