John Hurrell – 5 March, 2013

Looking at an Auckland context I'm guessing that this show's organisers were fully aware of the irony of this erasure being paralleled by the Pride Festival dropping the ‘Gay'. Was it denial or expedient suppression - another version of ‘the love that dare not speak its name' - too embarrassing to mention? (And is ‘Queer' scarier?) Surely not?

As part of the Pride festival in Auckland at the end of February, this Artstation show featured ten artists: eight women, one trans-sexual, one man. Exploring a queer politic, its theme revolved around the title of a work by the great American artist, Robert Rauschenberg, a gay male who is an inspiration to this group of mainly women artists, all lesbian.

In the compact little catalogue, essayist Jacquie Phipps refers to Jonathan Katz’s account of how in 1951 the newly married Rauschenberg abandoned his pregnant wife (Susan Weil) and ran off with fellow painter Cy Twombly, commemorating his new relationship with this exhibition’s eponymous work that alluded to two men dancing. This canvas he painted over in black two years later when he formed a new relationship with Jasper Johns. In this exhibition the original dance step notation was alluded to on the floor by Ponti (but changed from a waltz to a tango), and on the back wall, the (obliterated) black painting was referenced by Ash Spittal.

So why did Rauschenberg alter the 1951 work? To reassure his new lover of his fidelity is one interpretation. That he was uncomfortable with his sexual candour within an artwork is another.

Looking at an Auckland context I’m guessing that this show’s organisers were fully aware of the irony of this erasure being paralleled by the Pride Festival dropping the ‘Gay’. Was it denial or expedient suppression - another version of ‘the love that dare not speak its name’ - too embarrassing to mention? (And is ‘Queer’ scarier?) Surely not? Was it political - because ‘gay’ is perhaps linked to male homosexuality only, or even if both male and female, is too bourgeois and mainstream? This is more feasible, though ‘Pride’ on its own seems so inclusive as to be sycophantically inane in its generosity. Straight Pride? Onanists’ Pride? Abstainers’ Pride? You’re kidding.

In this show there were several highlights. Ahilapalapa Rands and Imogen Taylor presented Gay Dogs, a video of sections taken from the reality television series, The Real L Word, featuring the canine pets of lesbian couples, and reinserting the G word into the conversation, as well as perhaps making a joke about contagious sexuality, animals taking on the orientations of their owners.

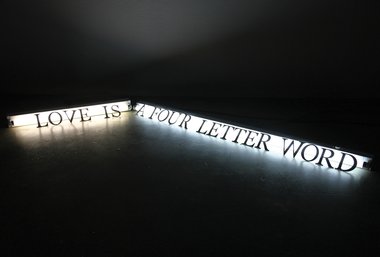

Deborah Rundle had two compelling works. One consisted of some glass chandelier trinkets, hanging from the ceiling and manufactured originally to be suspended as a group from a glass lightshade. Coincidentally these found objects (each one unique) looked like fecund Neolithic goddesses, with exaggerated bellies and sex organs. Her other contribution was a fluorescent tube on the floor with letters in front spelling ‘love is a four lettered word’. The tube was divided in two and bent, so while the ‘bent’ aspect was witty it also suggested impotence or the loss of phallocratic domination. Four lettered words include of course ‘dyke’, ‘poof’, ‘slut’, and ‘homo’.

A contemporary of Rauschenberg, Andy Warhol’s fake Brillo Boxes were the main reference of a clever photograph by Jo Mears. Depicting a dog food carton she found and discreetly modified to allude to the various clothing and behaviour codes of ‘masculine’ lesbians, it became a witty, flipped-over play on Warhol’s own ‘fairy’ persona, implying his ‘remasculinising.’

One work that surprisingly seemed to refer to Renaissance sculpture, particularly the standing bronze figures of David by Donatello and Verrocchio, was a statue by Louise Purvis: Golden Boy, a lithe schoolboy in tight short pants with an erection. The work was made of silicon, bronze and 24 caret gold; an erotic object designed to be looked at, if not lusted over. The young man’s thoughts themselves, beyond salient horniness, were a mystery. He could have been heterosexual and unobtainable for gay lovers - but that was not the point. The work was about fantasy (his radiant beauty - there to be gazed upon), the beholder’s projected desire; a call for love - even unrequited - a summonsing of aching devotion as a priority.

John Hurrell

Advertising in this column

Advertising in this column Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

This Discussion has 0 comments.

Comment

Participate

Register to Participate.

Sign in

Sign in to an existing account.