Warren Feeney – 25 March, 2013

In all of Millwood's images, real life itself is up for question and maybe the best that an artist and viewer can make of it is a glimpse: moments in between other moments and memories, reconstructed and reshaped to make sense of. If nothing else, at least the act of painting is an action intended to provide meaningful reflection and commentary.

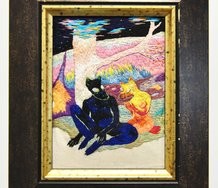

Snapshots of holidays in faraway places and photographs of childhood and family have been central to Adrienne Millwood’s photo-release prints and canvases for at least the past three years - and in Real Life they still are, yet these new works also manage to be so much more.

Millwood’s art deconstructs and reassembles narratives and distant memories, curiously populating them with floating, biomorphic shapes, designed and dressed in the best of retro-interior colours schemes. Poised somewhere between abstraction and story-telling her prints have acted as both sentiment and formalist construct and this is a tension that remains of significance to the works that make up Real Life.

In Toyko, the subject from the late 1940s of Japan’s downtown capital is as much a photograph that documents a post-war tourist image, (well-suited for Western consumption - looking at, rather than with, its subjects), as it is a consideration of the artist’s source material, contributing to a formalist work-of-art-in-progress, with colourful jigsaw amoeba laying equal claim to the surface of the picture plane. In Real Life, images are forever in a moment and process of becoming and disappearing, anticipating realisation as pure abstraction or figuration as memory made visible, and in doing so, her practice is both a touching and a feisty visual experience.

Real Life also represents new territory for Millwood. In the surprisingly large scale of a number of these works, she seems to have reconsidered the scope and potential of her subjects. A new-found confident and pleasure in the premise of an arts practice centred upon a dichotomy promises that there is more potential in the content of her iconography and its development than previously anticipated. The self-assurance of Real Life is apparent in images that are subtle and perplexing: does the narrative dictate to the coloured network of shapes that are in the act of materialising around and within its figures and forms, or is it the other way around?

And the premise of nostalgia or reflection is as implicit in the abstract, paint-by-numbers forms and contours as it is in the familiarity of images like the Grand Canyon or Mt Fuji. If only painting and the resolution of an image were as simple as the sureness and authority of a paint-by-numbers puzzle. It is the kind of formula for success that any serious artist can only look back upon with envy, the promise of a solution from childhood right in front of your eyes, solving all the dilemmas as to how to bring to resolution the artwork that has just been nagging away, day after day. In drawing attention to the naivety of such solutions, Millwood also touches upon a tenuous faith in the very act of painting and the premise of an artist being able to give vision and substance to an idea through the materials of paint or ink on canvas.

In all of her images, real life itself is up for question and maybe the best that an artist and viewer can make of it is a glimpse: moments in between other moments and memories, reconstructed and reshaped to make sense of. If nothing else, at least the act of painting is an action intended to provide meaningful reflection and commentary. Real Life implies that the pleasure of looking and asking such questions has value. Could we, or should we, wish to ask for more?

Warren Feeney

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects Advertising in this column

Advertising in this column

This Discussion has 0 comments.

Comment

Participate

Register to Participate.

Sign in

Sign in to an existing account.