Mary-Jane Duffy – 19 March, 2013

.

It was July in Paekakariki. The sea was as flat as an old surfboard - the sign of a southerly wind. From the beach I could see a figure on a board 500 metres offshore. He dipped a paddle now this side, now that. As I approached he slid into shore on the tiny waves that passed as surf. It was Simon Shepheard, artist and surfer. He had parked up his motor home and travelling studio (the MoHo) nearby. For a few weeks he’d hang his works-in-progress in the stumpy taupata and on the side of the MoHo, and spend the day looking at them and adding bits of paint - between contemplating the view and riding the wintery waves.

The best artists make us look at things in a new way. Their work stamps some aspect of the world with their vision. For artists working in contemporary landscape, that’s difficult. It’s hard to look at our landscape without being reminded of the paintings of it. The Colin McCahon hills north of Plimmerton, the muddy Woollaston weather that constantly assails Wellington, and the Brent Wong clouds that pass over the harbour on a clear day are pretty hard to argue with. How can an artist contemplating landscape compete with such branding?

Painting itself is in question. Students who want to learn painting at art school are deterred. I write in a room with a young woman who was discouraged by both peers and tutors. Poor painting! It’s just not conceptual enough. It’s just not enough anymore. Everyone says photography is the new painting. Where does that leave painting?

I have heard Judy Millar talk about painting as a field of enquiry, painting as research, as archive. What would Simon say his research was? I’m not sure but I know that our footprints on the land are the subject of his work. His scrubby brushy images function with an appreciation for living in the landscape - for freedom camping and surfing. But more on that in a moment.

Simon and I sat in the Moho in Auckland six months later filling in the gaps since we had last seen each other. The Moho was parked on a slope outside his house in Grey Lynn. That day he’d been out at the national surfing championships at Piha in the Moho. While his friend GT showed some potential sponsors the sizzle they’d put together for a new television show, Simon painted outside. Around him surfers came in and out of the water discussing the waves and critiquing their performances. He eavesdropped and looked as he added paint to cane and metal trays. This was the first chance he’d had to paint since we’d seen each other in Paekakariki.

“Why don’t you use the MoHo as a studio in Grey Lynn?” I asked.

“It’s all about context” he replied. “Painting in the MoHo parked on a slope at the back of Grey Lynn makes me feel poor. Parked up so that I can watch the surf finals out my window at Piha, I’m a millionaire. But I’m super-rich in Sandy Bay. We can have the MoHo parked right next to the beach, and I don’t have to feel like some sad bastard who can’t afford a studio, who hasn’t ‘made it’ in the art world.”

I was in Riverton with my family several months ago. We were staying in a house perched on a point with a view out three sides - over the estuary, the river and the little township. We oo-ed and ah-ed over the views and wished for our own. But my brother the architect was adamant: you don’t live in the view. And he’s right. That’s where landscape painting has made its place - to remind us of the bigger, the wilder, the more beautiful places beyond our daily ones.

In the sixties Colin McCahon transformed the landscape genre. Landscape became the subject in front of which to deliver his critiques of society, his reprimands. “YOU MUST FACE THE FACT: the final age of this world is to be a time of troubles.”[1.] And even without text, his paintings of the stripped and dried hills of Kapiti and Canterbury are accusing. “Yes” they say, “look at the monoculturalism. Look what it’s done.”

Simon also makes the landscape a site for provocation and criticism. He paints his landscapes on bits of rubbish. Over the years I’ve known him, I’ve driven around many inorganic rubbish collection days while he gathered objects for new paintings. Once you start looking, so much suggests landscape. The last time he visited my house, he stared at a Formica breadboard, on which we’d chopped meat for years. The middle was worn back to the wood. ‘Look at that island over your sink’ he said. I looked, and yes, there really was an island on the chopping board now.

And this is what his work is like. The surfaces he collects, the discarded objects and pieces of junk have something about them that suggests an image. Over the weeks and months that he works on them, he adds paint, sands, inlays, hammers and buffs to bring out the image he’s seen.

These images include shaggy bushy bluffs, islands, seascapes, rivers, swamps, tree stumps, perfect waves, trees, headlands - a catalogue of particular northern views. Portholes and windows on to bits of land. And why those particular vistas? They’re the places where he surfs, where he camps, where he parks the Moho. Good things are connected to them. And he revives other people’s rubbish with these connections.

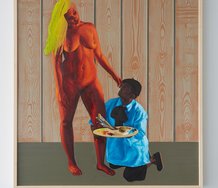

En masse in the gallery space, the works are a delight, a catalogue of domestic detritus - cane or metal trays, rattan screens, shutters, dismantled chairs and tables, old surfboards, fire screens, cushions, and all manner of timber - renewed with a purposely hokey aesthetic. And while that makes the works easy on the eye, there’s something disquieting about them too.

Take the plushly upholstered seventies chair-back framed with chrome. The wavy pattern of the red upholstery has become a bloody river bordered with the lush greens of mangrove tracts. Or the vertically slatted chair with the coastal bluff painted on the sides of the slats. As you pass from either side slivers of view appear and disappear. Now you see it, now its gone. Or the swamp with nikau painted on the weave of a cane basket - the texture as dense and rich as any wetlands, but dark and foreboding.

Simon calls the work ‘budget mysticism’. I laugh. Yes, this is pop eco art - ironic and self-depreciating - but the message is there. Here are the places we love that are undermined by development, consumerism, so-called progress, with greed and blindness. But this isn’t the roaring voice of McCahon pointing his biblical finger and telling us to get our shit together. The tone of these works reminds me of a contemporary of McCahon’s, poet Hone Tuwhare. There is something of Hone’s daggy style in Simon’s work; some moralising delivered with humour and a gift of the gab.

“… Daddy-long-legs has joined his / ancestors by way of a hungry trout’s / stomach & stomach ejector. / Happens to people too, nowadays - with / sharks hangin’ around a lot.” [2.]

But observing the mixed reception of Simon’s work in the art world over the years, I am reminded of McCahon’s legacy. The art historical canon says that McCahon is the greatest artist New Zealand has ever produced, and that is generally accepted. We can look back and accept that his art had a fire-and-brimstone social conscience, and love that about it. But to do this we also have to accept that is it provides a precedent for art with a social conscience.

Simon’s combination of rubbish and image describe our imposition on the land. I think these works are also thumbnails for a bigger vision - the artist as watchdog and activist. Which also explains why he doesn’t paint his urban landscape. Living in central Auckland is too infuriating. In the urban landscape, Simon’s work scrutinises council decisions: where are public funds spent, and what are corporations up to? And of course, there’s plenty of material in these enquiries.

In 2007 the silos on Wynyard Peninsula came on the radar. Public submissions were sought. Simon proposed that the silos - big round buildings built originally for grain storage - become gallery spaces. He didn’t want to see them demolished and replaced with in-fill housing. The peninsula is a small fragile piece of land without proper sewerage or infrastructure.

“This is about creating an authentic, breathing cultural heart that generates economic morale from the harbour out through the suburbs all the way to Albany and South Auckland. It is the original, unique New Zealand experience in the centre of a generic concrete jungle. Business will bask in it and so will our reputation. The entire economy benefits rather than just the usual predetermined interests,” he wrote in his submission to the council. The proposal included planting, and discreet food kiosks. It considered the coastline and access to the peninsula, and cited a contemporaneous New York project that had transformed defunct industrial structures into galleries and public spaces.

That was in 2003. On a visit to Auckland in early 2013 I discovered that Auckland City Council have decided to run with the idea - the silos have become galleries. An exhibition programme is in place for 2013.

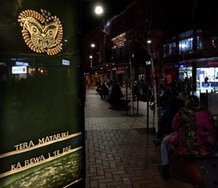

In the urban context, the subtlety of Simon’s landscape works is replaced with direct messages, with signage. Signs started to appear in his practice in the 2000s. The first signs were poetic homages to the Automobile Association. These signs contained an image and pointed at one end. The way to a place was indicated by a landscape. They reminded me of slightly evolved cave paintings. They were lyrical and enigmatic.

I loved these works. They were subtle and suggestive - they showed without telling. From these Simon moved to a more direct address using the aesthetic of the protest sign. This series was inspired by the activities of the speedway at the back of Grey Lynn located in the middle of a residential area. In the 2000s the speedway increased the number of annual meets. The noise of cars accelerating and breaking regularly echoed around the streets driving the residents to despair.

For Simon it bought into focus the whole problem with cars in Auckland. He started planting protest signs around the area. They were made with his signature materials and aesthetic and contained humorous but provocative message about the noise pollution. “Noisy Carsholes”. ”Pretty Ugly Parade”. And there were other signs too about other issues: “Save Sheds from Dickheads.” “Pull down politicians instead.” ‘ ’Worst past the post.” ‘ ’Free China.” ‘ ’Your bullshit out of our stream.” ‘ ’Sly Shitty Latrino.” ‘ ’Vodafoney friend.”

It’s hard to find work by New Zealand artists that’s engaged with wider politics. Public galleries are happy to bring in artists from China and America who have something to say about their political situations, but any artist using their work as a vehicle for protest in Aotearoa is sidelined or ignored. Even though we applauded Ralph Hotere when he protested the proposal for a smelter at Aramoana in the eighties; and know New Zealand art would be dull without the feminism, anti-nuclear and identity politics of last century; and that Maori artists have changed the way we think about colonisation and it’s ongoing impact amongst many other things. But a lippy Pakeha from Whangarei who questions how the money is spent and why our heritage is being demolished for developers… Shut Up! [3.]

I don’t want to promote Simon as some kind of eco warrior-cum-artist or the next big thing - he’s been around too long for that. I’ve poked and prodded around a few things here, made some claims and drawn some connections. One of them is that we see art in New Zealand that looks new because we don’t know its international sources. We see work here that brings together local and international connections, and work that continues or builds on traditional practice. We have a rich and diverse art scene, and we see a bit of it in commercial and public galleries. The rest you have to look for, see out of the corner of your eye, or glimpse over the sink.

Mary-Jane Duffy

[1.] Text from Storm Warning, 1980-81, acrylic on unstretched canvas.

[2.] From “Deep River Talk” in An Anthology of New Zealand Poetry in English, eds. Bornholdt. J, O’Brien. G, and Williams. M, OUP, 1998

[3.] Although as I write the Mahara Gallery, Waikanae, has a programme around a political poster exhibition about art and activism.

Recent Comments

Roger Boyce

Part 2 Please recall that Bice Curiger, curator of the Venice Bienalle, prominently showcased three luminous Tintorettos in her 2011 ...

Roger Boyce

Part 1 First, Ms. Duffy, let me compliment your admirably crafted and evocative encomium – bringing “artist and surfer” Simon ...

Advertising in this column

Advertising in this column Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

This Discussion has 2 comments.

Comment

Roger Boyce, 5:14 p.m. 25 March, 2013 #

Part 1

First, Ms. Duffy, let me compliment your admirably crafted and evocative encomium – bringing “artist and surfer” Simon Shepheard’s work to my non-native attention. I can’t, of course, get a reliable read from the accompanying photo-reproductions … but the evident wit of Shepheard’s socially interventional signage, and his recounted observations, were enough of an indicator, joined by the affection and vigor of your text, for me to seek in-the-flesh examples of his work.

I’m weary of being mistook for a reactionary, whilst engaged in the incidental defense of something that, these days, hardly begs defending … anywhere else, it seems, ‘cepting New Zealand or, say, Dubai; places where prophet-like and Prophet-sanctioned institutions seek to foreclose select genres of depiction.

I imagine there’s barely sublimated irony in your passage below:

“Painting itself is in question. Students who want to learn painting at art school are deterred. I write in a room with a young woman who was discouraged by both peers and tutors. Poor painting! It’s just not conceptual enough. It’s just not enough anymore. Everyone says photography is the new painting. Where does that leave painting.”

But, in a country harbouring more than its global quota of literalists and would-be art-theorists I daren’t let it pass without comment … lest some purblind youngster miss your paragraphs’ irony.

Roger Boyce, 5:15 p.m. 25 March, 2013 #

Part 2

Please recall that Bice Curiger, curator of the Venice Bienalle, prominently showcased three luminous Tintorettos in her 2011 survey. The curator’s decision was reportedly instigated by firsthand phenomena. What she observed, in prospecting younger artists worldwide, was aggregate movement toward deliberately crafted embodiment. As opposed to institutionally-driven deconstructive strategies – strategies that serve, mostly, to illustrate theory.

Curiger’s observational bias is could admittedly be colored by where she comes from professionally ….“I am not the kind of curator who comes from cultural studies, philosophy or sociology and as a result I am skeptical towards exhibitions which try to illustrate theory.” Reports from other credible sources and from personal observation confirm Ms. Curiger’s trend-analysis is, at least, in the ballpark.

Arriving New Zealand eight years ago was a little like passing through a space/time continuum … backwards. Considering the U.S.

horror-show I fled, one could figure that’s a good thing. And for most part it has been. However, the privileged cultural status of theory-driven (tail wagging the dog) artworks in Aotearoa was temporally baffling – given that internet had promised to keep us all abreast with every blessed thing.

So, having said what I’ve just said, and in doing so further submerging my already soggy professional prospects … in my beloved adopted country, I’ll edge further toward professional-abyss by suggesting that painting - at least where I currently lecture - is neither discouraged nor scorned by peers or tutors. In fact we like it. I do however discourage my students from using the content-free descriptor LIKE when critically analyzing artworks.

Young-uns, if you want to paint, come see me and mine. We’ll do right by yo

Participate

Register to Participate.

Sign in

Sign in to an existing account.