Will Gresson – 24 August, 2013

In a time where issues of surveillance and the role of the state in public life are still being questioned, often with direct references to this period which we have supposedly moved past, Sounding the Body Electric: Experiments in Art and Music in Eastern Europe 1957-1984 feels like a timely meditation on the challenges faced by some in expressing themselves and the possibilities of innovation under hardship.

London

Group Show

Sounding the Body Electric: Experiments in Art and Music in Eastern Europe 1957-1984

26 June - 25 August 2013

The Calvert 22 Foundation and its not-for-profit gallery, located in East London, were founded in 2009 to help foster links between Russia, Eastern Europe and other former Soviet territories and the rest of the world. Since its inception, it has hosted a wide variety of different exhibitions and associated events and talks, to draw connections between contemporary art practices both under Soviet rule and since the collapse of the Eastern Bloc in the late 1980s/early 1990.

The current exhibition, Sounding the Body Electric: Experiments in Art and Music in Eastern Europe 1957-1984 is actually only a part of a larger show by the same name shown at Muzeum Sztuki in Lodz from June - August 2012. Both the exhibition in Lodz and the smaller London iteration are interesting in that they explicitly seek to divide the work into two separate time periods, using the Prague Spring in 1968 as a turning point.

The works in the upstairs of the gallery are noticeable for a sense of playful experimentation and almost joyful naiveté. Central in this group of works in many respects is the role of the Experimental Studio of Polish Radio, founded in 1957, where composers worked to create what must have been viewed as bizarre abstract sound pieces that wouldn’t have sounded out of place among the more well known German artists from that period such as Stockhausen. The distinction made here, and extrapolated upon further in Agata Pyzik’s recent article for the Calvert Journal, is the way in which these sounds were tied to the “social and material world,” rather than the abstraction which was front and centre in the works of many western sound art and electronic music pioneers.(1) This suggests an element of social influence even as the works themselves simultaneously challenged aspects of the Soviet status quo.

In accompanying texts to the exhibitions this sense of openness is attributed to the period which followed Joseph Stalin’s death in 1953. In the same article, Pyzik also argues that the openness was a sort of recompense for the brutal suppressions in Hungary and Poland during the 1950s.(2) As David Crowley writes in the accompanying text, after the incredible paranoia and madness of Stalin’s purges and show trials, Moscow declared a ‘Scientific Technological Revolution’ which sought not only to forward the Soviet Union’s international agenda (think weapons and space programs), but also to bring a kind of “technocratic rationalism” to the average Soviet citizen.(3)

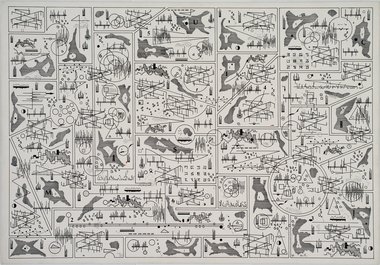

While this undoubtedly suggested a more rigid and pragmatic approach, what it also allowed for was a wealth of innovative compositions which included the production of graphic scores, manipulating/”damaging” records with tape and other interventions in a way which anticipated turntablism and sampling and also the creation of large scale installations which encouraged not only performances from artists and composers but also allowed for audiences to participate in the creation of new sound works. What also becomes clear from all of these different strands is the significant link between audio and visual practices. Milan Knizak’s records are unique not just for the way his destroyed vinyls sounded, but also because they could be shown as entirely separate visual works, as well as a form of notation, blurring the lines between these different mediums. Milan Grygar’s works, including Living Drawing and Tactile Drawing, also combine elements of graphic score, performance, sound and video, while his use of children’s toys feels in keeping with the light hearted and playful elements in the works around it.

Downstairs at Calvert 22, the works take on a more serious note. While the pieces upstairs, with their unconventional manipulation of new and old technologies into bold new pieces undoubtedly served as political challenges to the strict realities of Soviet life, the works downstairs feel more overt in their political undertones. After the severe repression of the Prague uprising, when it became apparent that attempts to open up life behind the Iron Curtain were not going to be easily achieved, artists started to incorporate important everyday realities of their day to day into their works, particularly with regard to surveillance and the ‘jamming’ of Western radio broadcasts.

While in 2013, ‘culture jamming’ connotes something potentially satirical and comical, in the mid 20th Century in the East of Europe it was a method used by Soviet authorities to limit the proliferation of Western ideas and media. Perhaps no work serves to illustrate the significance of this medium better than Just Transistor Radios, a collaborative composition between Szabolcs Esztenyi and Krzysztof Wodiczko, where eight performers tuned and manipulated portable radio receivers while having their ears plugged with soundproof plugs. To produce any sound outside of the state sanctioned norm was an act of subversion and a clear commentary on, and challenge to, state control.

Similar challenges can be seen in Komar & Melamid’s piece, Music Writing: Passport, which was composed in response to Soviet authority’s refusal to allow the pair to travel to New York in 1976 for the opening of their first exhibition in the United States. The score is derived from the texts found within the Soviet internal passport, and was performed not only in Moscow, but also in fourteen other countries by friends of the artists, symbolically removing the barriers of political and ideological difference.

A third work which stood out in the second half of the exhibition was a further collaboration, this time between Jozef Robakowski and Eugeniusz Rudnik. Using Rudnik’s electroacoustic music, recorded at the Experimental Studio of Polish Radio, Robakowski created a moving image work where the structure of a red rectangle expands and contracts along with the music. Created using a diaphragm the work references not only the traditions of Soviet avant garde art, but also a growing interest in the relationship between sound and image, as well as sound and the human body. The contractions of the red rectangle also bring to mind notions of claustrophobia and paranoia, clear comments on the political climate of the time.

For me personally, the stand out work was Zoltan Jeney’s piece Round. Created from a piece written for two prepared pianos, piano, harp and harpsichord, each of the twelve tones of music was linked to a vertical stripe that would obscure an image of a public space outside a subway station in Budapest. As the piece plays, the stripes flash on and off, always hiding part of the image. The work speaks to the blossoming of new music and film practices of the time (the piece was recorded at the New Music Studio in Budapest and the film constructed at the Bela Balazs Studio, both vanguard studios in the development of their respective mediums), while also addressing ideas of oppression and the intrusions into public life committed by the ever watchful Soviet backed authorities.

In a time where issues of surveillance and the role of the state in public life are still being questioned, often with direct references to this period which we have supposedly moved past, Sounding the Body Electric: Experiments in Art and Music in Eastern Europe 1957-1984 feels like a timely meditation on the challenges faced by some in expressing themselves and the possibilities of innovation under hardship. The use of radio waves as a sort of recapturing of disputed mediums also calls to mind contemporary examples such as Wikileaks and rise of social media and independent bloggers and activists who are working to reclaim the means of communication and disseminating information to combat larger political and ideological forces.

Will Gresson

(1) Pyzik, Agata, ‘Waves of the future: rediscovering Russia’s sound art pioneers’, (http://calvertjournal.com/comment/show/1340/russian-sound-art-sound-in-z), pub. Aug 13, 2013

(2) Ibid.

(3) Crowley, David ‘Sounding the Body Electric’, pub. Muzeum Sztuki, 2012

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects Advertising in this column

Advertising in this column

This Discussion has 0 comments.

Comment

Participate

Register to Participate.

Sign in

Sign in to an existing account.