Will Gresson – 1 February, 2014

What is immediately striking is the vitality of Höch's work as part of the Dada movement, brimming with sharp political and social commentary. The show establishes Höch's interest in embroidery and ornamental pattern as a precursor to abstraction and the ground floor of the gallery displays an incredible wealth of works from the post World War I / Weimar Republic period.

Comprised of over 100 works from across seven decades of artistic practice, Whitechapel Gallery’s new retrospective provides a fascinating and rewarding look at the oeuvre of German artist Hannah Höch.

Beginning in 1912 when Höch moved to Berlin and continuing until the artist’s death in 1978, the exhibition moves from early work and Höch’s fruitful period with the Berlin Dadaists, into her artistic production under the ever growing spectre of economic collapse and the Nazi regime in the late 1920s and early 1930s. Moving upstairs, the show examines Höch’s work in seclusion during the war years 1933-1945 before exploring her triumphant and jubilant post World War II pieces.

What is immediately striking is the vitality of Höch’s work as part of the Dada movement, brimming with sharp political and social commentary. The show establishes Höch’s interest in embroidery and ornamental pattern as a precursor to abstraction and the ground floor of the gallery displays an incredible wealth of works from the post World War I / Weimar Republic period.

Within this body of work are many of the better known collages for which Höch is famed. Works like Staatshäupter (Heads of State) (1918-20) parodied German political figures of the time, showing Friedrick Ebert and Gustav Noske looking less than dignified in their bathing trunks, in a manner which might conjure memories of MI6 Chief Sir John Sawers’ Facebook gaffe where his wife posted holiday snaps of him in his trunks the day after being appointed security chief. Elsewhere, items like Hochfinanz (High Finance) (1923) address the unholy union of politics, industry and the military as Germany and the rest of Europe hurtled towards the impending economic crisis of the late 1920s.

The works sitting alongside these better known pieces add to their power. On one side of the ground floor gallery is a series related to Höch’s work with an unrealised anti-revue alongside Kurt Schwitters named Schlecter und Besser (Worse and Better) (1925). While the project itself never materialised, drawings and sketches from Höch’s planned stage, set and costume designs again show her keen sense of satirical wit and the crucial political undertones in much of her work. Elsewhere, the series From an Ethnographic Museum presents an implicit criticism of colonialism and a biting commentary on the role of women in European society. The mix of (mostly female) body parts, ethnographic objects, as well as imagery and suggestions of plinths or displays all address the presentation of the body, notions of “the exotic” and colonial and nationalist politics. These works take on an even greater significance when one considers Höch’s position as a bisexual female artist in a time of rising conservatism, particularly under the National Socialists.

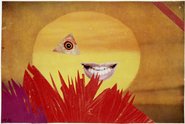

Upstairs the two smaller gallery spaces provide both sides of Höch’s conflict with the Nazi regime in Germany between 1933 -1945. The first room contains the scrapbook work Album which was made while Höch hid herself away quietly away from the censor’s eyes on the outskirts of Berlin. Album combines photographs of women and African tribes with images of wild flora and fauna. In her wartime seclusion, Höch continued to address notions of the ‘New Woman,’ and furthered her exploration of the ‘exotic,’ while secreted away. The natural imagery seems fitting here, like plants and flowers appearing in the cracks of a pavement.

The second space on the other hand is almost euphoric. An audible sense of relief can be palpably felt through the gallery containing the works coming in the immediate aftermath of World War II. All of these works contain words like journey, dream, rhapsody and peace, or address notions of “the fantastic,” with colours and shapes hinting at new opportunities, new directions and a new sense of freedom.

Throughout the show, quotes from Höch and others speak to the issues of the time, and Höch’s sense of possibility after twelve years horror under The Third Reich’s rule is both poignant and infectious. The final work, Lebensbild (Life’s Portrait) (1973-75) is a large scale collage, which speaks to much of Höch’s major thematic concerns throughout her long career like the position of woman and a relationship with the natural world, as well as issues of personal identity. Ending the exhibition on this note is fitting, in part because it acknowledges her interest in looking back, but also as a final bold testament to her fiercely engaging body of work.

Will Gresson

![Hannah Höch, Ohne Titel (Aus einem ethnographischen Museum) (Untitled [From an Ethnographic Museum]), 1930, collage, 48.3 x 32.1 cm. Museum für Kunst und Gewerbe, Hamburg Photo: courtesy of Maria Thrun](/media/thumbs/uploads/2014_02/Image-2_jpg_380x125_q85.jpg)

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects Advertising in this column

Advertising in this column

This Discussion has 0 comments.

Comment

Participate

Register to Participate.

Sign in

Sign in to an existing account.