Peter Dornauf – 1 June, 2014

The title, 'House Life', is taken from a documentary of the same name that examines a dwelling designed by the controversial architect, Rem Koolhaas. The doco, however, explores the interior of the building from the point of view of the cleaner employed to dust and polish. The construct of the house takes some unorthodox risks where functionality balances precariously with matters of beauty.

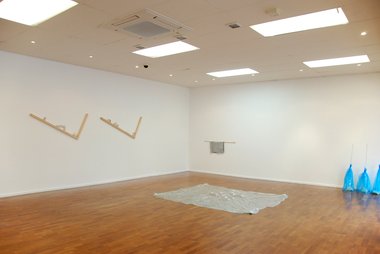

Only a couple of years out of art school, Larissa Goodwin and Kelsey Stankovich are two emerging artists currently showing at Pilot in Hamilton. They have collaborated here to create a sideways look at house décor, or at least considerations connected with that whole arena to do with objects, their materiality, scope and limitations together with how they exist in a vague and intangible space that falls between aesthetics and functionality.

The title, House Life, is taken from a documentary of the same name that examines a dwelling designed by the controversial architect, Rem Koolhaas, in 1998, which is located in Bordeaux. The doco, however, in true provocateur fashion, explores the interior of the building from the point of view of the cleaner employed to dust and polish. The construct of the house takes some unorthodox risks where functionality balances precariously with matters of beauty and the work in the show reflects this conception, exploring that equivocal place which lies somewhere between the useful and the elegant in all its ambivalence.

Goodwin’s first work, Runner, is simply a very basic DIY loom, constructed of wood, pushpins and string in which a half-finished network of woven twine hangs down from the mechanism representing the beginnings of a hallway runner. The work as a whole seems to hover between pure mechanism and toy in the act of creating something that will become a thing both functional and beautiful, existing in a no-man’s land where potential and actual play off each other.

It recalls the deliberate unfinished work of Penelope in Homer’s Odyssey where a home is made dysfunctional by absence, where beauty is unravelled each night by necessity, where a juggling act is played out between colliding and contrary demands. The Koolhaas house is also a precarious performance floating between aesthetic consideration and the ordinary requirements of living pushed to extremes. Runner thus assumes the proportion of metaphor for the duality inherent in the world of aesthetics and practical demands, where sometimes the meeting of the two creates failure.

Her second piece, Autumn Wreath, has the delicacy of a simple line drawing. Using an ordinary piece of string, she sets up a context which defines a space that takes the appearance of a preparatory sketch, mapping possibly the placement of a doorway against a wall. Attached to the draped string is a small piece of silver tape that acts like a miniature flag. It has no functional purpose other than the smallest gesture toward some visual appeal and neither does the yellow painted end of the slightly bowed dowel from which the string hangs rather loosely, other than to provide an aesthetic echo to the yellow strips of tape pinning the rod to the wall.

Thus functionality meets and juggles with the play of aesthetics, and that frisson is reinforced in the title, Autumn Wreath, a reference to American scented candles. The candle as functional object is obsolete in the modern world but finds new purpose as a room freshener which functions as a sort of ‘artistic’ quality in a round-about way. For Goodwin, it chimes with her interest in objects which exist despite being essentially redundant.

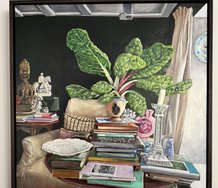

Goodwin’s standout contribution, Pivot Support, delineates shelf-like structures that operate at an unconventional angle, serving as precarious scaffold for abstract ceramic sculptures - handmade art works constructed from self-hardening clay and copper wire. The forms are somewhat ‘imperfect’ Miroesque configurations and come with a Japanese minimalist aesthetic. This is the place where the practical and the beautiful seem to completely coalesce, acting as complementary elements in a marriage of more than convenience. And yet the ‘perfect’ fusion of qualities is set at tension in the hazardous angle at which everything exists.

The second personality in this twin act is Kelsey Stankovich who predominately presents herself as a fabric artist. Her materials have essential a domestic quality - felted fabric, rubber, cotton thread, plastic and stuffing. All the works are elusively untitled, unprepossessing and partake of a kind of sculptural homely quality. Most simply lie on the floor close to a wall, as if left there awaiting some future purposeful act, possessing qualities that hover somewhere between mystery and sheer functionality.

Two of the works are folded arrangements of sheeting material that give off a sense of either having fulfilled their purpose and are waiting for storage or lying ready for some slightly strange and eclectic use. They exist in an ambiguous space between material associated with a building site, (like folded tarpaulin) and something approaching a Dali conception - hybrid creatures that speak of the surreal, but in the same breath, voice the banal.

One of the works is a drop-sheet, made of sheer plastic which the artist has painted with extreme subtlety using light blue. Her practice is to take familiar materials and manipulate them slightly so as to skew their recognition. The plastic has been cut up into squares and then hand-sewn back together with cotton thread to form a strict grid pattern. Lying on the floor it covers a random collection of plaster balls, presenting a place where materiality meets abstract aesthetic, where the temporal and transitional butt up against the notion of intransience. She describes these pieces as “handmade ready-mades” that play with various dualities, here with the fusion of the domestic and the industrial which throw up fertile contradictions and flexible references.

The same dynamic is captured in a work consisting of a row of identical blue plastic wrappings that hold plaster bases in which an extruding wire is affixed and protrudes from out the top of the wrapping. These enigmatic forms conjure some floral or ornamental arrangement waiting to find placement in the furnishing of a house, while at the same time take on the semblance of something between art and not art.

House life is the space where humans construct their aesthetic defence against the world of random exigencies, a tenuous fort, a place part beautiful, part functional, fragile and tenuous, marked with constructive impermanence, a shifting arena where life is played out in a precarious fashion - where we manage to survive, despite being unnecessary, holding on as we tilt.

Peter Dornauf

Advertising in this column

Advertising in this column Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

This Discussion has 0 comments.

Comment

Participate

Register to Participate.

Sign in

Sign in to an existing account.