Alice Tappenden – 9 August, 2014

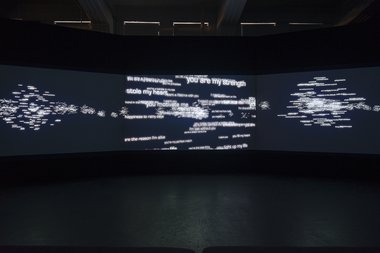

'Supermassive' (2013) is another video installation, projected across four large screens which are slightly tilted to surround the viewer. Adding to the immersive nature is the pervasive muzak; loud and slightly New Age, it lulls you into a state of relaxation, reminiscent of a day spa. On the darkened screens, galaxy-like clusters of words begin to appear, dancing in and around each other as they advance and/or fade.

Wellington

Grant Stevens

What We Had Was Real

Curated by Robert Leonard

28 June - 6 September, 2014

What We Had Was Real, Grant Stevens‘ current exhibition at City Gallery Wellington, takes its title from one of the fourvideo works on display: Crushing (2009). Set in a darkened back room of the South Gallery, the four-minute-long DVD is set to sad piano music, not unlike the credits of a bad daytime television show. On a black background, a stream-of-consciousness narrative is projected word-by-word, beginning slowly with ‘baby I’m really tired’, before the clichés (their triteness at times unbearable) progressively speed up, revealing themselves to be the story of a relationship break-up:

‘I have lost my ability to think and to feel but I know what we had was real I just wanted to be with you to be in your life but you have taken that away’; ‘how you used to look at me our dinner parties with our friends going to the markets together shrimp pasta’; ‘I’m still hopeless I loved you from the start I don’t feel well we even talked about getting a dog don’t you remember’.

In the outside world, such banalities would be easy to ridicule, but in the gallery setting the viewer is far more likely to pause and consider - smirking one minute, cringing the next - as they recognise something they themselves might have thought of or even said out loud.

Like much of the work in What We Had Was Real, Crushing not only draws attention to the proliferation of the cliché in contemporary culture, but goes a step further by exposing the inadequacy of language to express complex emotions. How often have you started an awkward conversation with a version of ‘I think we need to talk about us’?

The exhibition begins by presenting the viewer with another video, If Things Were Different (2009), alongside three other pieces that curiously aren’t mentioned by curator Robert Leonard in his introductory text. The wall labels of Particle Wave (2012), General Manager (2008), and Sonny (2012) simply list the works’ titles and dates, leaving viewers to fend for themselves in deriving meaning. This isn’t necessarily a bad thing, but it is interesting that Particle Wave, in particular, contains no direct references to pop culture or clichés - no discernible ‘way in’ for many viewers - and in its position directly opposite the gallery’s entrance, it may have benefitted from a little more explicatory attention.

Particle Wave has six panels which fluctuate through the colour spectrum like holographic postcards as the viewer walks past. They’re indeed very beautiful, and provide a nice visual respite from the narrative moving image works, but many visitors I observed bypassed them quickly in favour of the videos (which could, I suppose, speak more about society’s obsession with television than anything else). In terms of the wider exhibition, it aligns with Stevens’ existential investigations, comparing the very foundations of our universe to the banality of breakfast where on the opposite wall, Sonny‘s green-tinted plate of bacon and eggs, shaped like a smiley face, simultaneously mocks and amuses.

Next to Sonny, If Things Were Different plays on a wall-mounted screen (not as a projection) telling another version of a break-up story, this time utilising actors. An ordinary-looking couple sit in an ordinary-looking living room, and proceed to discuss their relationship troubles in vague, very ordinary terms. Their American accents aren’t particularly convincing, leading one to assume the actors are Australian like Stevens. As their conversation proceeds, the voice track slowly shifts until her voice speaks when his mouth moves, and vice versa.

Though Stevens has taken a narrative and placed it in the ‘real world’, the conversation is less specific than Crushing, and goes around in circles without acknowledging any actual events: ‘I think we need to talk about us’;’ I don’t know what I want’; ‘I didn’t know that’s how you felt.’ This introduces a surreal quality, which takes it past the Home and Away stereotype into a more interesting realm, while still managing to make viewers squirm slightly again with recognition. The only slight detriment to the work is in its presentation; it originally lacks background music, but in this context, the soundtrack from Supermassive next door filters through the wall, somewhat diluting its extreme awkwardness.

Supermassive (2013) is described by Leonard as the highlight of the show. It’s another video installation, projected across four large screens which are slightly tilted to surround the viewer. Adding to the immersive nature is the aforementioned muzak; loud and slightly New Age, it lulls you into a state of relaxation, reminiscent of a day spa. On the darkened screens, galaxy-like clusters of words begin to appear, dancing in and around each other as they advance and/or fade.

Several clusters of words are presented at any one time, meaning that the viewer can’t possibly keep up or spot them all: we can, however, tell that they’ve been grouped in clouds with like-minded words. I spot medicines (diazepam); mantras (breathe in breathe out); daily tasks (clean the house); philosophical questions (is the universe both finite and infinite?); natural disasters (landslides); celebrities (Sean ‘Diddy’ Combs); Indian food (spinach and cheese naan) and romantic gestures (couples massage).

The word clouds are at once banal and philosophical, representing both the microscopic and the macroscopic - our individual concerns (what’s for dinner tonight?), wider societal trends (who played point guard for the LA Lakers for the entirety of the eighties?), and the foundations of our universe (what is the meaning of life?) - this tension is at the heart of What We Had Was Real. Stevens’ ever-increasing ability to select ambiguous conversations and social media communications might be highlighted, but it’s the content about the creation of the subject that’s interesting - the realisation forced upon the viewer about whether they’re even individuals at all.

Alice Tappenden

Advertising in this column

Advertising in this column Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

This Discussion has 0 comments.

Comment

Participate

Register to Participate.

Sign in

Sign in to an existing account.