Alice Tappenden – 2 July, 2014

Clearly, an existential narrative is prominent throughout 'what is a life?', but while the exhibition asks the ‘big questions', there's no sense that it's in a hurry to answer them. The challenge facing any art reviewer is to take the visual and reduce it into a textual form, but the pages of my notebook are perhaps evidence of how difficult it is to describe this exhibition.

I’ll admit it at the outset: I’ve never read Mallarmé, Wallace Stevens, or Michael Ondaatje. Most of the poetic and philosophical texts that Kim Pieters has taken to name the works in her exhibition what is a life? that crawl along the bottom of her paintings in impossibly tiny handwriting, are unrecognisable to me. So it’s somewhat fortunate that in an interview with Hamish Clayton, Pieters described her work as ‘a call to the person who pays attention, to generate meaning for themselves, from their own sensitivities and knowledge, and in their own way, or - and this is valuable - if they so desire, to allow an absence of meaning.’ (1) Pieters thus gives the viewer licence to form a personal response, and while the ‘absence of meaning’ part will come later, I’m going to start mine with the arbitrary knowledges series.

These eight paintings were the final works I came to, on the bottom floor of the Adam Art Gallery. They’re titled using lyrics from the Talking Heads single Once in a Lifetime, and given Pieters’ integral place in New Zealand’s experimental music scene, I suspect it’s no coincidence that their baby-blue base coats are gratifyingly similar to the undulating graphics which bookend the song’s music video, and eventually swallow frontman David Byrne into a digital abyss (I may not have read Mallarmé et al, but I have spent copious hours listening to Talking Heads). Like the vast majority of Pieters’ works, the arbitrary knowledges paintings consist of abstract forms, and while it would be easy to try to compare them with something from ‘real life’, nothing quite seems to fit.

The bulbous shapes are of varying colours - some grey-ish blue, some dusky pink, some pastel-ey olive green, and some contain flashes of brighter hues. Some are bigger, some smaller; some clustered together and others separated. There’s a scribble of black here, a spidery blood-red line there. The most tempting word to describe these shapes is to say they float - but that doesn’t feel right, and nor do they tumble, fall or rise. The easiest way to put it is to say that they just exist.

Clearly, an existential narrative is prominent throughout what is a life?, but while the exhibition asks the ‘big questions’, there’s no sense that it’s in a hurry to answer them. The challenge facing any art reviewer is to take the visual and reduce it into a textual form, but the pages of my notebook are perhaps evidence of how difficult it is to describe this exhibition. Once I’d gotten to ‘…to walk horizontally along the edge of a word, blinded by sun to forget what was seen, and what there is, and beneath heel, to gather at the fiction of a hill‘ (2011, from the fiction of a hill series), I had all but given up on writing coherent sentences and had (pleasingly) reverted to drawing the subtle forms I saw, hidden amongst the great washes of sage-green paint.

The abstract nature of Pieters’ paintings does, admittedly, incite the viewer to experience an ‘absence of meaning’ while looking at them. However, even when Pieters uses elements of the real world in her works - particularly in her films and photographs - she still manages to make me momentarily, at least, forget what I know about it. Magnet (2009, audio by SEHT), for example, is projected in the Adam’s stairway space, eschewing its boundaries and spilling over the white pillars on to the wall behind.

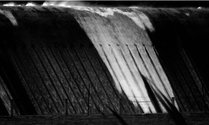

Sitting in the darkness, I caught the film’s beginning; a night time scene, showing glowing - almost skeletal - power pylons. The low-frequency humming of SEHT’s audio permeated the space, mimicking the slowly-throbbing frames, as the camera panned left and then right, zooming in and then out, to reveal that my first impressions were wrong. It was daytime, and that darkness which I’d thought was the night was actually the shadow of a hill. Fading to black, the scene changed, to focus on a great stream of water rushing over the edge of a dam. Momentous and beautiful, spilling and falling, it’s not at all unlike the paintings from, say, The Mallarmé Suite (2013). And like those, too, it’s not at all clear about what it means. But the truth is, it doesn’t matter.

In the audio commentary to their ground-breaking documentary Stop Making Sense, David Byrne described his desire to bring himself and the audience into some kind of trance, and Pieters’ immersive exhibition similarly has the potential to daze and confuse. Despite the fact that I went in to what is a life? knowing I’d have to think about it, at the end I truly had no idea how long I’d spent there, and I wouldn’t be surprised if Pieters’ own making-process is a little bit the same. Like the snatches of poetry, philosophy and song lyrics Pieters takes for her titles, this exhibition unravels slowly. It twists and turns, never quite being tied down. While Talking Heads was my ‘way in’ to considering the exhibition, others will find different paths, other ways to ponder the show’s existential themes. When asking a question like ‘what is a life?’ you know you’re going to get as many answers as respondents.

Alice Tappenden

(1) Hamish Clayton in conversation with Kim Pieters, April 2014. Wellington: Adam Art Gallery, accessed 29 June 2014: http://www.adamartgallery.org.nz/wp-content/uploads/2014/05/Interview_Pieters_WEB.pdf

Advertising in this column

Advertising in this column Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

This Discussion has 0 comments.

Comment

Participate

Register to Participate.

Sign in

Sign in to an existing account.