Andrew Paul Wood – 9 September, 2014

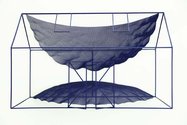

Dawson's small work frequently gives the impression that they are models for something much larger, which is part of their appeal. This is also true of the schematic gabled house structure of 'Interior Blue' with the clever illusion/allusion to sky and land inside is obviously a continuation of Dawson's 'Interiors' series, first exhibited at the Elva Bett Gallery, Wellington in 1979 and kept alive as a source of continued exploration into the present.

Neil Dawson is without question best known for his public outdoor commissions like Ferns, Chalice, and of course the celebrated Globe of the 1984 Magiciens de la terre exhibition in Paris. His gallery shows are far fewer and further between, but no less captivating. In an enclosed space, Dawson’s fondness for visual tricks with positive and negative volumes and optical illusions makes for an unsettling experience, but the fun and lightness of touch are still there.

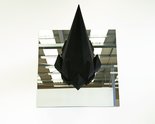

In some of these new works Dawson uses wall-mounted mirrors to create the illusion of a completed object extending into non-site, or perhaps invading our space from looking glass dimensions beyond. In one corner is Uccello’s Chalice a large wire-frame-like three-dimensional recreation of famously B-team quattrocento artist Paolo Uccello’s well known perspectival exercise. A mirror is similarly used in Spiked, a geometrical form based on Christchurch Cathedral’s defunct spire. The sculpture emerges from the wall, black, phallic and inscrutable - the Monolith from 2001: A Space Odyssey meets Darth Vader’s codpiece. It is incredibly effective, majestic and even intimidating. The mirror serves to double up the spire shape into a tetrahedral structure which has been a frequent motif in Dawson’s work since the installation of his sculpture Spire in Christchurch’s Latimer Square in 2013.

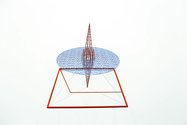

This double steeple-based form repeats itself in a number of variations in smaller, marquette-like works of refined geometric ornament and, to my eye at least, remind one of model starships with solar sails or Alcubierre drives. Called Inspirations, it is almost if venerable Victorian gothic revival architecture has been playfully translated by means of Dawson’s signature minimalist pop into something sleekly futuristic. They have a fascinating Fabergé-like quality. Dawson’s small work frequently gives the impression that they are models for something much larger, which is part of their appeal. This is also true of the schematic gabled house structure of Interior Blue with the clever illusion/allusion to sky and land inside is obviously a continuation of Dawson’s Interiors series, first exhibited at the Elva Bett Gallery, Wellington in 1979 and kept alive as a source of continued exploration into the present. It is characteristic of Dawson to find continued fascination with the symbolic and physical possibilities inherent in the simplest of forms. Typical of these smaller works, the detail, wit, scale and robust materials invite a tactile response.

One of the delightful things about Dawson’s work is that for all their skilful engineering, wit, trickery, symbolism and virtuosity, they are never inaccessible. The exhibition includes two large wall works that are primarily decorative. Black Haloes resembles a pattern of interlocking sprockets and cogs that abruptly terminate to give the illusion of an invisible square frame. The detailing has a vaguely Polynesian feel to it - perhaps reminiscent of a Lonnie Hutchinson cut out - but this may be entirely accidental. Clouds is more complex. Dawson likes to play recursive opposites in his work, counterpointing the light and ephemeral imagery of feathers, ripples and paper darts with sturdy metal construction and simple geometric compositions. This is a philosophical game that goes all the way back to the Neoplatonists of the Medici court as explained in Edgar Wind’s Pagan Mysteries in the Renaissance (1958) where combining opposites symbolised the greater transcendental truth of the Oversoul. In Clouds, a stylised cumulonimbus is constructed out of overlapping baroque swirls in turn made up of stylised iron girders.

Situational aesthetics and rarefied post object art has been on the decline overseas for a while now, exacerbated by the Global Financial Crisis (slumps and depressions always seem to encourage markets for tangible objects and retinal pleasures). I think that’s what I like most about Dawson’s work; it’s clever without needing an undergraduate course in Derrida to know what’s going on and it is completely independent of the pieties, fashions and theories of much contemporary art, making it always a refreshing and pleasurable experience.

Andrew Paul Wood

Advertising in this column

Advertising in this column Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

This Discussion has 0 comments.

Comment

Participate

Register to Participate.

Sign in

Sign in to an existing account.