John Hurrell – 12 February, 2015

The most successful ‘homage' is On the Use of Irony, a small work which references the wonky INRI sign in McCahon's Crucifixion: The Apple Branch so that it - Malone's own ‘King of the Jews' sign - is hung crookedly with a hemp cord and copper nail. It also seems like a sort of declaration of Malone's own personal disbelief in Christianity. Or (with that reflexive title possibly being ironical about irony) is he espousing it?

With his current residency at the McCahon House in Titirangi about to end and a new show coming up at Te Uru, this Hopkinson Mossman presentation is Malone’s first Auckland dealer show for two years.

Now a permanent inhabitant of Warsaw, the residency allows Malone (one of the founders of Teststrip) to step out of Europe, come back here and have a fresh look at the achievements of Colin McCahon. He could have chosen not to and tested out other things.

Because the location is steeped in forest atmosphere and specific art historical references it is really no surprise for any other artist (because Malone is usually unpredictable) that McCahon takes a leading role in the image production. And technically as a painter working on loose canvas, Malone is closer to the feel and tactility of McCahon than say fellow appropriator Imants Tillers (from the late eighties and early nineties) with his use of paintstick on canvasboard.

That these are painted images is noteworthy, because Malone is usually known for performance, installation, and occasionally sculpture. They are still typically ‘Malone’, blended with materials like obsessively hoarded packets and labels, and characteristically exploiting multiple semantic layerings that examine ‘self’.

I initially mistook I & l for I and I, a great eighties Dylan song about the split self. In fact it is Iyaric or Dread-talk, a Rastafari expression meaning ‘You and I’ that speaks of a synthesis between the speaking individual, the addressed person, and Jah (God). Given Malone’s long interest in Rastafari culture, and his wit in mixing in McCahon’s theological themes, this makes a lot of sense.

Two works in particular reference double ‘I’s, ‘I’ as a motif being widely found in McCahon’s painting as a descending beam of sunlight cutting through rain clouds. I & I is painted on a dismembered canvas army bag, flanked by two ‘I’s framing a Zigzag cigarette-paper man. The much larger And per se And, punning on Ampersand, has an ampersand sign in its centre framed by two pale ‘I’s - and references Numerals from the mid-sixties and Teaching Aids a decade later, teasing out approaches to addition and the act of counting.

The key work in the show seems to be Omega and Alpha (Kauri, Unfinished), a painting where a curved dotted line of birds from McCahon’s Rosegarden (1974) paintings is mimicked by two strings of kauri gum (amber) beads, The Marys at the Tomb (1950) outside the empty tomb are alluded to by text and a painted circular door, and the resurrection is wittily alluded to via McCahon’s Kauri studies (1954) and a drop cloth on the floor saying ‘Die Back’ - the tree disease seriously threatening our native kauri forest. In Malone’s clever hands, death is ordered to retreat, to get back, to submit to the re-emergence of life. There is a level here where through his appropriation Malone is giving McCahon life - resuscitating him by introducing his work to new (hitherto uninformed) generations.

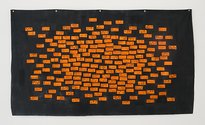

Not all his paintings work. Arhythmia which uses hundreds of heart pill packets in a horizontally spread field seems to reference Flounder Fishing Night, French Bay (1957) but only half gets there, as does Six Dais in Otago & Canterbury which salutes 80s indie Dunedin rock bands and would have been more effective mimicking the proportions of McCahon’s original grid structure of Six Days in Nelson and Canterbury (1959). Many works are too rushed, or with the Tau Cross / broom leaning Cloak reliefs, oblique.

The most successful ‘homage’ is On the Use of Irony, a small work which references the wonky INRI sign in McCahon’s Crucifixion: The Apple Branch (1950) so that it - Malone’s own ‘King of the Jews’ sign - is hung crookedly with a hemp cord and copper nail. It also seems like a sort of declaration of Malone’s own personal disbelief in Christianity. Or (with that reflexive title possibly being ironical about irony) is he espousing it?

This ambiguous layering is also found in Cloak III (The Wretched of the Earth). The cloak presents hundreds of suspended labels from luxury fashion garments, hung like pleading votive fetishes in a shrine. Its title references the poor labourers in thirdworld sweatshops but (as a twist) it could just as well reference fashion consumers like Malone himself, lovers of good design who through their purchases and consumerist addiction inadvertently perpetuate the exploitative capitalist ethos. There’s a possible soul-searching, a tortured ambivalence - condemning while through display, promoting and still desiring.

John Hurrell

Recent Comments

John Hurrell

Thank you for this, Ralph. It's fascinating. Dylan, as everybody knows, is very secretive, and there is no mention of ...

Ralph Paine

Bob Marley's ghost perhaps. Did Bob & Bob ever meet?

Ralph Paine

Given Mr Malone’s propensity for webs of affinity and associative practices of all kinds, let’s not be too hasty in ...

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects Advertising in this column

Advertising in this column

This Discussion has 3 comments.

Comment

Ralph Paine, 12:24 p.m. 13 February, 2015 #

Given Mr Malone’s propensity for webs of affinity and associative practices of all kinds, let’s not be too hasty in dismissing the Bob Dylan connection. Dylan’s song ‘I and I’ appears on the 1983 album Infidels. Sly Dunbar and Robbie Shakespeare—the famous reggae rhythm section and production duo—play on the album, and it is said that prior to the recording sessions Dylan had been spending a little time with Bob Marley. Regarding the song itself, here’s an excerpt from Christopher Connelly’s review of the album: “In the delicate ‘I and I,’ Dylan struggles against the weight of old artistic identities, turning the Rastafarian expression for ‘God and Man’ into a meditation on his own changes through time” (Rolling Stone, 24 November, 1983). This sounds like a good description of what Mr Malone is doing here— with McCahon as local guide.

Ralph Paine, 12:37 p.m. 13 February, 2015 #

Bob Marley's ghost perhaps. Did Bob & Bob ever meet?

John Hurrell, 2:31 p.m. 13 February, 2015 #

Thank you for this, Ralph. It's fascinating. Dylan, as everybody knows, is very secretive, and there is no mention of Marley in Michael Gray's exhaustive 'Bob Dylan Encyclopedia', or Bob's own 'Chronicles'. There doesn't seem to be any evidence that the two Bobs ever met.

Participate

Register to Participate.

Sign in

Sign in to an existing account.