John Hurrell – 11 March, 2016

Possibly most intriguing is Logos, a scattered array of ‘Blutak' pieces, with each tiny pale blue cast pinned into the wall. It is really unsettling. The spread apart replicas are indistinguishable from the real thing, and of course don't look like ‘art' at all. With an imaginative leap, they take on a symbolic quality of unseen sustainers; hidden dollops of metaphysical Plasticine maintaining order throughout the universe; squishy bonding units from the Divine that hold elemental components together.

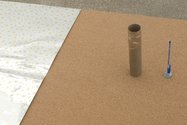

These look like framed paintings on the wall, two noticeboards for pinning stuff onto, and some store-bought items on a couple of cork desks, but - as Hany Armanious has been making cast polyurethane resin sculpture for well over five years now - we know he will never exhibit readymades. Materials listed on the catalogue sheet are vitally important. More than any title. The work is antivisual in the sense that any enthralling seduction it possesses comes from what you know, not what you see. Only the minced up and compressed cork is in fact cork. Those desks are what you think they are.

The paintings are Giclée prints of fingerpaintings apparently made by his small son, and on the large wall we see what seem to be scattered bits of Blutack, waiting for some posters to hold up.

Looking at the objects on the cork desks, the eponymous Hollow Earth features a sheet of what seems to be a length of printed Christmas wrapping paper, the cardboard core of some Glad Wrap , and a biro vertically jammed into a wad of wrapping paper is made of Blutak. The wrapping paper is made of digitally printed vacuum formed polypropylene (you can just detect an unnatural thickness), the cling film core, Blutak wad and biro case are made of pigmented polyurethane resin, and the writing tip of the ball point pen features 18 carat gold and chrome.

For other works like Geisha (the ‘noticeboard’) and Pro Bono (the other cork table), the bits of thin soap, balsa sticks, pharmaceutical capsule packaging, crumbling sheets of asbestos and blobs of poured cement - all typically are made of polyurethane. It’s unnerving the way that substance is so versatile and protean.

Possibly most intriguing is Logos, a scattered array of ‘Blutak’ pieces, with each tiny pale blue cast pinned into the wall. It is really unsettling. The spread apart replicas are indistinguishable from the real thing, and of course don’t look like ‘art’ at all. With an imaginative leap, they take on a symbolic quality of unseen sustainers; hidden dollops of metaphysical Plasticine maintaining order throughout the universe; squishy bonding units from the Divine that hold elemental components together.

Another item that fascinates - but on a visual level - is Don Quixote, a cork and polyurethane wall work where the cast polyurethane sections are arranged like a pictographic drawing, using chunks of running shoe soles. The charcoal grey and blue ellipses are organised rhythmically in swirling linear arabesques. Looking at the title you can just detect the profile of the wandering knight riding his horse, while the shoe rubber hints at incessant travel and little repose.

The whole area of sculptural verisimilitude is an interesting one, especially if you compare carving (Glen Hayward, Fischli and Weiss) with casting (Armanious, Arps, Burrell) and the striving by artists for the creation of new meaning - beyond virtuosity and technical flash - using (amongst other things) humour, incongruity and metaphor.

John Hurrell

Advertising in this column

Advertising in this column Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

This Discussion has 0 comments.

Comment

Participate

Register to Participate.

Sign in

Sign in to an existing account.