John Hurrell – 9 June, 2016

While irrefutably photographic prints, they mimic aspects of drawing and painting too. You could say they are a combination of Chris Marker, Georges Seurat and Francis Bacon. And as statements they encourage the contemplation of a collection of images as opposed to single portraits, something which is often (for some) too intense, and - likely as not - too theatrical. There is a quality about a community of moving visages that holds one's interest longer than a solo image that verges on the confrontational.

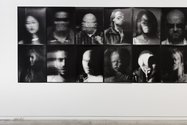

The two long walls of the downstairs Two Rooms gallery have been converted by Australian artist Trent Parke into a kind of gridded photographic mural, featuring deliberately granular and smudgy portraits of Adelaide citizens he captured when they were standing on a chosen corner of inner city streets. At times the swirling fields of glittery grainy specks make the moving or contorted visages into abstractions, so that the documented physiognomies start to lose their identifiable parts.

Each bank of pinned-up (often agitated) images has a unifying rhythm from the dispersed use of highlighting that pulls the horizontal grids together. Two high, one is fourteen photographs long, the other twenty-one.

While irrefutably photographic prints, they mimic aspects of drawing and painting too. You could say they are a combination of Chris Marker, Georges Seurat and Francis Bacon. And as statements they encourage the contemplation of a collection of images as opposed to single portraits, something which is often (for some) too intense, and - likely as not - too theatrical. There is a quality about a community of moving visages that holds one’s interest longer than a solo image that verges on the confrontational, but which you can mentally walk away from. It’s the way they inevitably collectively interact. With lots of contrasting variations to compare, the corny ones are not so troubling.

These matte b/w prints, because they show sparkling motes of dust hovering in the air as clouds that form faces, seem to be presenting some grand metaphor for life itself, for the transience of existence, the omnipresence of death. The subjects’ clothing (its textures and patterns) and various eye accessories also play an important role expressively, along with hair and raking finger movements. We never see crisp detail - only vaguely suggested forms - so we have to make up the particulars, guess about individual peculiarities. Some portraits look skeletal or skull-like, with other heads like a pulled-over stocking or featureless ‘burned’ blob.

However it is this quality of brutal deformity that makes the best of these images so rivetting; deformity or monstrosity that has come from sudden movement blurrily hidden by accentuated grain. It is either the sideways or twisting movement or - if static while facing the camera - the obliteration of detail: the fact that normally accessible facial information is now hidden. This introduces a sinister quality where the tables are turned. The viewer in the gallery now seems to be watched while the photographed observer is unidentifiable.

Through the implementation of a double layer, not strata of three or four, there is maintained a sense of horizon that architecturally encloses the viewer and sweeps around to include the peripheral. There is something rattling about this encroachment of rear space (even with a single flat wall), the zone behind the viewer’s head.

I also notice that in sardonically titling the individual works ‘Candid’, Parke has the listed categories of child, man, or woman. I’m surprised in these days of transgender awareness that he doesn’t just say adult or child. Or even just human, so that the viewer’s imagination (and paranoia) is pushed further by the withholding of age. That way they really visually and mentally investigate the image before them.

This is in parts a disturbing installation that exploits the cumulative psychological consequences of gridded grainy physiognomies en masse. It is confrontational and chilling, with a sense of incipient violence and existential futility.

John Hurrell

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects Advertising in this column

Advertising in this column

This Discussion has 0 comments.

Comment

Participate

Register to Participate.

Sign in

Sign in to an existing account.