John Hurrell – 15 September, 2016

If you look closely at the different works by Hammond, McLeod and Wilkinson, you will notice there are two methods at play within each practice. An image or scene can have a clear symbolic reference and historic function within a stated structure (a narrative ‘explanation') - mythic or otherwise. Or a head (say) can inexplicably have two contradictory faces; or a prone body be a landform - both calculatedly flummoxing the viewer through indecision.

Auckland

Selected works from a private collection

Antipodean Gothic: Art from a Private Collection

‘Curated’ by ARTHIST 734 Art writing and Curatorial Practice students

September - 1 October 2016

In this highly eccentric but definitely successful show, the notion of ‘curation’ is upended by getting thirteen people to individually pick thirteen works out of a private collection, and although the oddball title (courtesy of William Dunning) is only vaguely pertinent (think ‘Antipodean Gothic,’ you’d normally bring to mind Jason Greig and Leo Bensemann), the cumulative effect is undeniably intriguing.

Firstly, it is fabulously exciting to see some very big quality examples of painting on display in Auckland. For while, for example, Bill Hammond: 23 Big Paintings did come to Auckland Art Gallery in 2000, Bill Hammond: Jingle Jangle Morning (2007- 8) unfortunately didn’t. Classy paintings large in scale are a rare event in Auckland. The last one I saw was Ron Left at AUT.

Hammond dominates this thirteen work exhibition with five paintings and rightly so, while Brendon Wilkinson had three items (one painting, two sculptures), and Andrew McLeod, two. In some expansive spaces these works could look contained or slightly pinched, but even in the comparatively (architecturally) cramped Gus Fisher they look supremely elegant. The hang is exemplary.

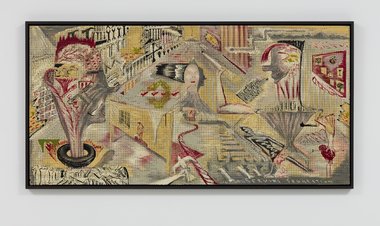

With the Hammonds, four are of the ‘humanoid /suburban neurosis’ variety, and one is of the later ‘shag/spirit people’ type. Personally I prefer the earlier, rawer, less slick works, and here there are two that consist of four butted-together canvases, each group collectively forming a big rectangle. I enjoy the angularity and roughness of Hammond’s execution; its unpredictability (controlled sloppiness) of paint application and image, plus the fact they are disruptively more about head comics, the deformities of Jim Nutt’s gender wars, and ‘straight’ satire (attacking orthodox careerism) than languid fantasies about pre-human Pacific history.

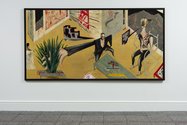

Of the thirteen selected items, six (the four earlier Hammonds - The Vagaries of Lingo, Serving Suggestion, Piano Forte, Animal Vegetable Acrylic - plus Andrew McLeod’s Shangri La, and Brendon Wilkinson’s Meat Dust) are what I’d call plot-shredding or anti-narrative works. Their images tend to be highly ambiguous; nothing is really definite, so meaning is constantly deferred or evaded. The other works are not so slippery, their semantic significance does not waver; their meaning is clear, mythical symbolism being fixed and underpinning layers stated. (Here I include: Hammond’s Hokey Pokey, paintings by Liz Maw, William Dunning, Anne Wallace, Andrew McLeod’s heavily botanical Untitled, Brendon Wilkinson’s ‘Edenic’ painting Internal Surface, and his sculpture, An Arm and a Leg (Mt. Eden Train Station).

I realise I may now be accused of being over reductive, for the two mindsets do sometimes overlap, but if you look closely at the different works by Hammond, McLeod and Wilkinson, you will notice there are two methods at play within each practice. An image or scene can have a clear symbolic reference or narrative function within a stated structure - mythic or otherwise. Or a head (say) can inexplicably have two contradictory faces; or a prone body also be a landform - made to calculatedly flummox the indecisive viewer. These images have a formal wit or entertainment value, but in the context of their whole composition, they are not part of any bigger story. The former (‘narratives’) tend to have deep perspectival space while the latter (‘meaning disrupters’) usually hug the picture plane.

Okay…here is another speculation to chew over: With electronic advertising (moving image signboards) now beginning to take over every street corner within the CBD - replacing conventional signage - large paintings are starting to become more and more antiquated as curiosities with static images: becoming rarer and rarer in private homes or corporate offices. Video art (with loops) might well replace them, especially if daily encountering of moving image onscreen (outside as ‘urban landscape’ and in the office, or home) becomes the new norm. Perhaps large format, static imagery (purchasable through dealers) will not be able to compete in the rush to attract new audiences. The pleasures of looking at static painted imagery might even die out, like a lost (soon to be forgotten) language.

Antipodean Gothic is an exciting show of ‘traditional’ work that has been around for approximately one and a half decades. It comes with a nice catalogue of thirteen very smart essays written by the thirteen selectors. If you feel that maybe New Zealand art has gone off the boil (including possibly even Hammond?) over the last ten or fifteen years, this presentation provides you with something definite to think about - to help evaluate.

John Hurrell

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects Advertising in this column

Advertising in this column

This Discussion has 0 comments.

Comment

Participate

Register to Participate.

Sign in

Sign in to an existing account.