John Hurrell – 9 September, 2016

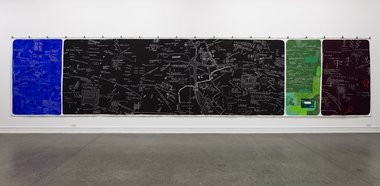

In Reynolds' 'Walk With Me', smaller blue and green panels flank the much wider black centre, and over all three he draws and writes (if there is a distinction) with his silver-paint marker pen, laying down assorted fragments. Everything has the ring of a classroom blackboard, and seems over improvised. The language doesn't have the authorative civic tone and extraordinary humour of Reynolds' other main experiments with McCahon and language, the reflective motorway painting-title signs.

With the title work dominantly presented on a long wall, this show of large recent Reynolds canvases draws out issues he himself has alluded to in Simon McIntyre’s curated AUT painting exhibition in St Paul St Gallery 3: the first iteration. In a side room, John Reynolds‘ set of five spindly placards last week proclaimed: ‘Toot for less text in art; Banish the painterly impulse; Drop the brush right now; Stop painting. Enough already; Please step away from that canvas.’

All these funny spoutings also apply to the Starkwhite show, for they obviously are contradictory (referencing different works) and true - with no space for irony. My view though is that the best canvas works are the smaller punchy constellations of linked spiderlike lines on fields with lovely rounded corners, while the weakest painting is the biggest one, with its intertextual multiple voices of jumbled quotations, scattered ad hoc musings on literature and art history, along with various maps and diagrams. One could wish Reynolds wanted to be Cy Twombly (with his indecipherable cursive writing) once more, and not John Ashbery or say, Leigh Davis, but that really is not the point.

The central issue is that of design skills and cognisance of viewer stamina. I’d rather look (at least initially, and perhaps always) at McCahon before Reynolds, Weiner before Kosuth, and Kay Rosen before Art & Language. The reason is that visual organisation is the hook that brings you to the ideational. It’s what gets you to stick around and think about what is in front of you. Appearance matters, and ideas need physical and formal properties to become manifest. They can’t exist in mental isolation.

Walk with me (the title) references a series McCahon made in 1974 where he painted a sequence of Roman numerals on the four quarters of one horizontal rectangle of canvas - with INRI in the centre, white on black. Many of the texts and maps depicted in the large Reynolds painting allude to April 1984 when McCahon disappeared for 12 hours on the eve of the opening of I Will Need Words, his survey exhibition in Sydney at the Power Gallery of Contemporary Art (as part of the Fifth Sydney Biennale, and curated by Wystan Curnow) - an event speculatively discussed in Martin Edmond’s brilliant book Dark Night: Walking with McCahon (AUP 2011).

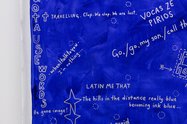

In Reynolds’ Walk With Me, smaller blue, green and dark purple panels flank the much wider black centre, and over all four he draws and writes (if there is a distinction) with his silver-paint marker pen, laying down assorted fragments. Everything has the ring of a classroom blackboard (a standard letter size), and seems over improvised. The language doesn’t have the authorative civic tone and extraordinary humour of Reynolds’ other main experiments with McCahon (alongside other artists) and language: the reflective motorway painting-title signs. Those are gloriously mischievous and cohesive (albeit esoteric), but this work struggles to make you interested in conceptually linking up disparate narrative and discursive elements. The best bits are the letter order reversals where Woollomooloo backwards (several times) implies the voices of owls or ghosts. McCahon meeting Harvey Comics (Casper and Spooky) is a nice touch - an apt metaphor for mental collapse and debilitating fearfulness.

The two Unhinged Text (Dark Night) works (also text-based) are not so airy as Walk With Me with its casual spontaneities. They feature dense writing as linear drawing, shifting alignments of compacted text you can dip into at will, but which (because of the vertical and diagonal lines of ‘word strings’) could be - for instance - an approaching swirling storm, some sort of implosion, or looking into the compressed muscular digits of a tightly clenched fist. Their graphic nature makes them a convoluted and nutty form of concrete poetry, an exploration of density and obsessive word printing that teases you to free-associate both seen and read images simultaneously.

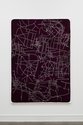

In contrast, the two stars of this presentation are - as mentioned - the What Is Not A Map works. As thrilling linear drawings, they lure you into a state of reverie as your eye tracks along the various dotted or continuous vectors, zipping along and jumping from one to the next when they intersect. They could be prisms, cobwebs, turtle shells, motorway turnpikes, pavement cracks, reptile scales, insect wings or ricocheting atoms. Packed with interpretative possibilities they are holistic, supremely visual, and (nevertheless) never totally free from language. This is hidden (not baldly stated - in your head, not written on canvas) but still omnipresent.

John Hurrell

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects Advertising in this column

Advertising in this column

This Discussion has 0 comments.

Comment

Participate

Register to Participate.

Sign in

Sign in to an existing account.