Terrence Handscomb – 2 December, 2016

Jealous Saboteurs' essays do not look too closely at the fragile subjectivity of desire and power that exudes from much of Upritchard's work. The exception to this is the wise inclusion in the publication of four literary texts that Upritchard commissioned to support her projects. By textually cloning the best parts of Upritchard's work and suturing them together in patch-work passages of internalised Gen-X emotion, these texts weave a complexity of desire that is uniquely Upritchard's. The commissioned texts give voice to form in ways that the curatorial essays cannot.

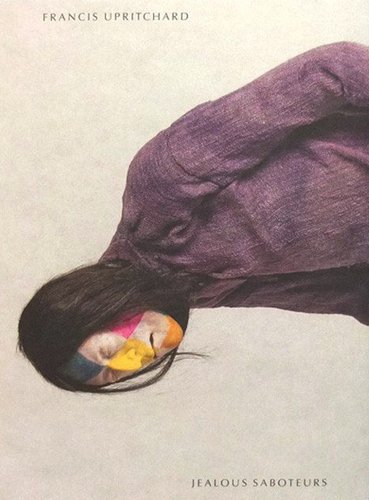

Francis Upritchard: Jealous Saboteurs

Edited by Robert Leonard and Charlotte Day

Essays by Robert Leonard, Tessa Laird, and Megan Dunn.

Interview with Francis Upritchard by Brian Griffiths

Contributions from novelists Deborah Levy, Haru Kunzru, David Mitchell and Ali Smith

Designed by Roland Brauchli

Softcover, 337 pages, 288 coloured illustrations

Published by Donlon, October 2016

Winner: the most risible opening utterance made in support of a New Zealand artist in a major New Zealand exhibition publication essay, goes to Megan Dunn for:

” … I was wearing a crop top and Francis was stroking my stomach. ‘Isn’t it unbelievable that we are all going to die?’ she said.” (1)

Modernist nostalgia may evoke the idea that artists have intuitive knowledge of deep truths - albeit sexual truths - but this sort of thinking is wishful. The blatant sexuality and feral animalism embedded in the cavernous vaginas or hilariously impossible hard-ons (2) of many of Upritchard’s little people make it difficult to separate their sexuality from that of the artist herself. Despite this, any exegetic unpacking of the sexuality of Upritchard’s forms, both representational and actual, would wisely avoid a guesswork pathology of Upritchard’s own sexuality, or a discussion of the complex issue of sexual representation in contemporary art, both of which seem dubious. In the current cultural climate, any well-heeled curator or essayist would be smart to avoid opening this can of worms. The curatorial agenda of Jealous Saboteurs seems to heed such caution - it politely steps away.

The three curatorial essays of the publication of Francis Upritchard: Jealous Saboteurs (released only in October, many months after the exhibition opened) include a worthy speculation by curator Robert Leonard of how some of Upritchard’s revisionist Māori taonga cleverly transcend twenty-first century identity politics; Megan Dunn‘s lazy anecdotal discussion of her encounters with Upritchard that somehow get spun into the idea that fake histories are embedded in Upritchard’s corpus; and Tessa Laird’s well-written eisegesis, burdened only by the unnecessary number of associative literary double-readings that she uses to give meaning to Upritchard’s work.(3) The curatorial industry of Jealous Saboteurs is prodigious, but one principle theme remains either unaddressed or discussed only in passing: the prevalence and role of sexual representation in Upritchard’s work.

Jealous Saboteurs‘ essays do not look too closely at the fragile subjectivity of desire and power that exudes from much of Upritchard’s sculpture. The exception to this is the wise inclusion in the publication of four literary texts that Upritchard commissioned to support her projects. By textually cloning the best parts of Upritchard’s work and suturing them together in patch-work passages of internalised Gen-X emotion, these texts weave a complexity of desire that is uniquely Upritchard’s. The commissioned texts give voice to form in ways that the curatorial essays cannot. Especially noteworthy is the unique and interesting solipsistic male voice that novelist Deborah Levy gives to The Thinker: “Is pornography dulling my libido?” (p. 15).(4) A delightful read. Instead, the official curatorial momentum of Jealous Saboteurs emphasises Upritchard’s many works that parody and satirise orthodox art-historicity and institutional museology. My purpose here is to test how, and to what extent, Upritchard’s many sexual representations stand up to critical scrutiny, and how the meaning of Dunn’s crop top anecdote and her idea of fake history can be cashed out.

Any aggressive post-modern feminist deconstruction of male identity, of the sort that was everywhere two or three decades ago, is satisfyingly absent from Jealous Saboteurs. If anything, Upritchard’s representation of men and male identity is given over to satirically exaggerated erections or benign penile appendages, which are “… no more profane than a small branch on a rather ridiculous tree” (p. 112). This is as close as Dunn, or any of the curatorial essayists, get to Upritchard’s erotic work.

As I see it, the emotional demeanour of many of Upritchard’s phallic and non-phallic male figures evokes the late modern image of pastiche man whose self-identity is not derived from authoritative successions of phallic power, such as historical patriarchy, but rather assembled from the fragments of social matter with which he is surrounded. (5) This is visually reinforced by the patchwork metaphor of argyle harlequin colour painting that covers the faces and bodies of many of her forms.(6)

Upritchard’s pastiche men are made up of bits and pieces of this and that, and despite the hilariously impossible hard-ons of some of them and the little stiffs of others, she is smart enough not to turn them all into farcical phallic heroes and then poke fun at them. The sexuality of these (not necessarily male) figures requires others to witness their moody sullenness that speaks more of compromised emotional disengagement and the social disenfranchisement that often follows the diminution of personal power. This is smart feminism.

Dunn had been spooked (and possibly seduced) by Upritchard’s personal touch to such an extent that she had to blurt it out at the beginning of her essay: “‘Yes.’ My tender underbelly was exposed. I felt unravelled like her mummy quivering on the floor …” (p. 108). In her typical anecdotal style, Dunn then mollifies herself and Upritchard’s less-than-transparent personal manipulations (artists do this a lot) by anecdotally elevating Upritchard’s artistic mythology in such a way that Dunn subtly lifts her own personal importance because she was party to a close personal encounter with Upritchard. Freud called this transference.

Dunn then goes on to unconvincingly fold the idea of false history into this bizarre anecdote. False history, with “… a glass eye permanently fixed on the future” (p.108), becomes the principle exegetic theme of her essay, into which she painfully injects the idea that Upritchard’s visual historiography loosely embeds a sort subjectivising futurity that somehow involves the denial of death. When it comes to Upritchard’s “wistful renditions” of Māori taonga, “I didn’t think Upritchard’s hokey mummy as [being] dead either” (p.108). That death is terminal but never final is a phantasy held only by the living. The ego will be larger in death than it ever could be in life, and something great will live on in the way our personal history is written.

The psychoanalytical contiguity of sexuality and death is notorious, and Dunn’s wan approach to death is underscored by how easily she turns her focus from the anecdote of Upritchard’s subtle sexual manipulations (with or without its morality intact) by insisting that her erect males are not ‘pornographically charged‘ (p. 24). Well, not in a San Fernando sort of way. She then emphasises the point by selectively choosing examples of Upritchard’s male figures that have weeny weenies [ill. 24, pp. 195-6]. On some obscure psychoanalytical level little dicks may indeed imply that death is inevitable, but benign and not to be feared. So be it, but beneath Upritchard’s school-girl artifice (‘Stiffy seems more innocent.‘ (p. 112)) her dicks and cunts are mostly erotic and unmistakably sexual. As I see it, the real power of Upritchard’s work lies in its sexual shamanism and not in the way that it visually rewrites established histories.

The title of Dunn’s essay is “False Histories” and she supports her historicist argument by quoting Walters Prize judge Carolyn Christov-Bakargiev from the year she awarded the prize (2006) to Upritchard for Doomed, Doomed, All Doomed:

“To understand the past … one does not need to incorporate it into a museum or archive, one needs to remake it, to recreate it, and thus make it personal, one’s own” (p. 116).

Accepting that Upritchard’s work visually rewrites history, albeit in a fake or satirical way, then this rewriting is itself trapped in the straightjacket of art-historical time. Herein lies a pathology.

If Jealous Saboteurs does rewrite an ageing form of institutional historiography and orthodox museology - and it does so in new and vibrant ways - then it also unwittingly reprises the art-theoretical notion of aisthesis, an idea recently offered up by French aesthetic theorist Jacques Rancière (7). If you think of the paradigm of universal beauty to be found in the subtle curvature of the Belvedere Torso, and argue that its aesthetic power is neither absolute nor universal - because the visual value of art is always locally determined and temporally isolated - then visual historiography is bound to time and place. Jealous Saboteurs is no exception.

Jealous Saboteurs provokes a made up art-historiography of diverse cultural milieux that sits a lot closer to the aesthetic values of late classicism, the academy and the antiquarian collector mentality of high imperialism, than it does to the complex narratological mishmash of ideas that tries to make sense of art in politically uncertain times, such as now. Nobody, least of all our artists and their work, convincingly occupy worlds that are not trapped in historical time: art as it was, art as it is now and art as it may be in the future.

What Jealous Saboteurs‘ retro-aesthetic stylings and crafted application does do to art history, is to present a delightful and timely distraction to the earnest technology-based art that has monumentally insinuated itself into mainstream art. In her Walters Prize apologia, Christov-Bakargiev noted that Upritchard’s work serves up an extremely welcome distraction from the technology-based art that these days seems to be everywhere. Ironically, her words portended the techno-heavy Walters Prize exhibition 2016, ten years after Upritchard won the prize. Given that “poor technology seems … to be increasingly topical today, in the digital age” (p. 116), Jealous Saboteurs‘ celebration of the handmade and its formal revival of ‘poor technology‘ would seem extremely timely.

Much of the current incarnation of New Zealand’s new technology-based art, exhibits an annoying over-produced electronic materiality that appears either to be rapidly descending into the theatrical mannerism of video, or into complex works that claim far too much technological self-importance than they deserve. Consider Tai Whetuki - House of Death, Lisa Reihana‘s, two channel video installation (2015), and Leah (2016) (single channel video animation), by Deborah Lawler-Dormer. The then doctoral student Lawler-Dormer worked in collaboration with the almost-famous University of Auckland scientist Mark Sagar (he met Prince Charles during his last NZ tour and showed him his research) the technology genius who makes this artwork actually work.

Reihana’s Walters Prize work was simply overcooked (can you believe that smoke machine?) and Shannon Te Ao’s video-intensive installations deserved to win. On the other hand, once you strip away the large-screen monumentalism, the advanced technical production (Sagar) and fashionable post-human backstory (Lawler-Dormer) of Leah - and finally navigate your way through the allegorical quicksands that can easily form when art meets technology - then, like many technology applications touting artistic credentials, the artistic veracity of Leah, suddenly reduces to nothing more than overstated visual novelty lacking canny artistic enterprise.

Not only does Jealous Saboteurs provide a welcome aesthetic relief from technology overkill, it also embodies elegant detailing that kicks back the rough grunge imperatives that continue to dominate much of New Zealand art. Yet it does so without seeming to abandon its own grunge ancestry.

Despite its popular success and prodigious aesthetic formalism, Jealous Saboteurs is burdened by historical ambivalence. Reprising aisthesis, no matter how timely it may seem, does not create the sort of temporal fractures that would be capable of throwing off the historical burden of time and place, or actually reforming them in ways that would completely transform art. Upritchard’s aisthesis-as-redux draws more from past art histories than pointing to a possible aesthetic future of art. The canny formalism of her hand-gloved sloths, cunt-bearing and horned-up little people, and repurposed antiquarian objects, all lacks the vatic intelligence and a special artistic knowledge that would be needed if the progressive orthodoxy of time is to be repurposed in the service of art.

If the show does evoke a fake history of sorts, then it is one that still tracks the orthodox aesthetic values and representative logics of the history of aesthetic style. If Upritchard’s work evokes a time-intrusive narrative, then it is one that would end up carrying a greater philosophical weight than it could possibly bear. The formal integrity of Upritchard’s objects, and her considerable attention to the detail of hands, feet, mouths and eyes, are art-historically time-bound to eras passed, but their subjectivism, materiality and process give them a contemporary flavour which binds them to our time; it is this which becomes mistakenly confused with a state of timelessness.

Any out-of-time elevation of Upritchard’s work acts only as a preemptive theoretical shield that diverts any critical gaze away from her not-so-different-from-the-past aesthetics, by suggesting that her work has cleverly transcended its associative past.

Any new subjectivism induced by art and somehow made visible in its form, must inevitably succumb to other forces; specifically, those of history itself. The subject of art “becomes visible only through the categories constructed by a specific historically defined society” (8). The categories of visibility that are strong enough to bring with them new forms of artistic knowledge are those which convincingly differentiate the now from the then. Jealous Saboteurs doesn’t do this.

Doting crowds flocked to the show when it opened at City Gallery Wellington; it was packed to overflowing for the artist’s and curator’s floor talk on the morning. Upritchard’s work is much loved by the Capital’s young arts crowd, especially women who admire her personal style (OMG, she was a model!). Her off-shore success is something that is easily inflated at home.

If the organising principles of art, life, the universe or whatever, are to be dissolved by the intellectual acid of skepticism, as much contemporary art seeks to do, then we are only left with pleasure as a primary principle. Undoubtedly, dodgy sexual antics lurk behind Upritchard’s veil of visual exaggeration, but along with Koons, she is smart enough to realise that the power of sexual pleasure and its representation lies just as much in satirical humour as it does in the complexities of a serious erotic gaze. There is basic aesthetic pleasure to behold in her work, in its prodigious detailing and canny choice of materials. Into this she cleverly weaves dark forces and sullen moods, all of which get cashed out on a level of representation that hides its pathos in ways that are not threatening enough to wound.

In a world that politically favours personal greed over economic equality; when the Enlightenment twin-visions of distributive justice and egalitarianism are being rapidly eroded by widening socioeconomic divides and the loss of personal privacy; when social media is rendering subjects visible, trackable and therefore governable; when ugly political manoeuvring is enacted in the twitter-sphere; or when any new issue, no matter how minor, feeds the hungry intellectual cynicism that informs much of contemporary art - it is little wonder that Jealous Saboteurs with its beguiling visual shamanism and fruitcake Sexualität, makes a timely cultural placebo for audiences that simply turn away from art that amplifies the cultural and political ugliness of our time.

Terrence Handscomb

(1) Megan Dunn, “False Histories” p. 108. … and thanks a lot for making me recall the most horrendous sartorial error from the early twenty-first century: the crop top.

(2) Upritchard’s Hobbits-with-hard-ons (Save Yourself ) that were hidden away upstairs at Venice LIII, are curiously absent from the show - the anecdotal reason given is that they have already been seen in NZ.

(3) Robert Leonard, “Adrift in Otherness” pp. 132-143; Megan Dunn, “False Histories” pp. 106-121; Tessa Laird, “Dustbin of Progress” pp. 174-185.

(4) Text reference page numbers are given in round parenthesis e.g. (p. 15) whereas image references are given in square brackets e.g. [ill. 24].

(5) Representations of this idea include, for example: A Beat (front cover), Horseman (p. 24), John (p. 42), Mandrake (p. 199), Yellow and Black Clown (p. 203), Breath (p. 223) and so on.

(6) In this respect, you need look only as far as the writings of renowned British sociologist Anthony Middens (b. 1938).

(7) Jacques Rancière, Aisthesis: Scenes from the Aesthetic Regime of Art, Verso, 2016.

(8) Joan Copjec, Read My Desire: Lacan Against the Historicists, London. Verso, 2015.

Advertising in this column

Advertising in this column Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

This Discussion has 0 comments.

Comment

Participate

Register to Participate.

Sign in

Sign in to an existing account.