Ralph Paine – 23 December, 2016

A city is all differing movement, all flows… And the channeling, regulation, policing, coding/decoding, quantification, and comparison of these flows: flows of matter and energy, commodities and bodies, atmospheres, linguistic flows, flows of affect, protocol, law, finance, data, and waste. A city is a giant circuit, circuit of circuits. But a city also consists of what goes elsewhere and what escapes it… And of what disrupts or jams the circuits.

So, over time, Hell became a storied place of sin and punishment, and we forgot that its original promise was never punishment but reunion, with the true, long-forgotten metropolis of Earth Unredeemed.

- Thomas Pynchon, Vineland

Just as there are different kinds of desert - ice, tundra, maritime, rock, sand, etc. - so cities are composed of different kinds of material: wood, concrete, brick, stone, glass, metal, carbon, silicon, plastic, etc. If we consider our endoskeletons as mineralisations of matter within our bodies that allow movement, cities may be conceived as our exoskeletons, mineralisations of matter outside our bodies that allow movement. (1) A city is all differing movement, all flows… And the channeling, regulation, policing, coding/decoding, quantification, and comparison of these flows: flows of matter and energy, commodities and bodies, atmospheres, linguistic flows, flows of affect, protocol, law, finance, data, and waste. A city is a giant circuit, circuit of circuits. But a city also consists of what goes elsewhere and what escapes it… And of what disrupts or jams the circuits. The city leaks, is out of control, corrupted. The city breaks down and decays. People pack up and move away. Shit-loads of money go unaccounted. Death squads operate. The city is blockaded, starved, fire-bombed, poisoned, stricken by disasters, plagues, and economic collapse - turned into a wasteland by pestilence and war. Witness Aleppo.

If the compulsive rate of flow for the classic modern city was one of an ever increasing speed - motor and factory, transport and weapon systems, the rush and buzz, jazz and futurism - the contemporary city inherits this obsession as an internalised and sleepless potential for numbing slowness: traffic jams, grid lock, telephone queues, security checks, downed networks, the catatonia of daytime television… Road Rage! Here in the glocalised metropolis all too often what gives a real sense of commonality and community is the shared experience of power cuts and breakdowns, accidents and disasters. But this is also where we locate the eventfulness of certain political actions, in slow movements, carnivalesque protest marches, sit-ins, occupations, barricade building, sabotage, riots, and the General Strike.

For Lewis Mumford it was a primordial and collective being-towards-death which manifested itself in the first built structures of history - the grave marker and the tomb - and hence “the city of the dead antedates the city of the living.” (2) Between a deep and unfathomable sense of ourselves as finite beings and the apparent permanence of any city we compose communal registers of Entropic time, sub-histories of the city as Necropolis, the world as Vampire and Catacomb. These histories speak of the city as a foundation of the deceased, built remembrance to the civil dead, to dead labour. Doubtless it is within a teeming half-life that capitalist wealth is produced and exploited, produced to be exploited, corrupted. Capital is accumulated corruption, realised corruption. As if already marked by death, the figure of the hyper-industrialised worker appears today as a zombie: factory worker, service worker, wage slave, precarious worker, migrant worker, illegal worker, domestic worker - all dismembered members of the contemporary living dead: “Above all, the State apparatus makes the mutilation, and even death, come first. It needs them pre-accomplished, for people to be born that way, crippled and zombielike. The myth of the zombie, of the living dead, is a work myth and not a war myth.” (3)

Most often it’s inside the “social being” of cinema - “between immobile bodies in shadow (the spectators) and moving bodies in light (the actors)” - that we encounter this work myth in all its “extra”-ordinary allegorical power. (4) Jump-cut to George A. Romero’s Dawn of the Dead (1978): a zombie epidemic is spreading across North America. They eat your flesh and drink your blood, and then you become a zombie. “What the hell are they?” - “They are us!” The movie begins in a television news studio where chaos reigns. The situation on the ground out in the urban complexes is no longer reportable, and in the studio and on the network a panic ensues - the very nerve centers of the Society of the Spectacle are breaking down. Escaping in a helicopter, the four protagonists of the movie eventually hole up in an abandoned suburban shopping mall. The mall appears as an amazing city in microcosm, seemingly safe, secure, and full to overflowing with everything imaginable required for survival. But it’s also a place the roaming zombies are determined to enter, perhaps only out of a memory of the habit of shopping. The mall acts as a remarkable socio-spatial analytic in Dawn of the Dead, one whose resonance extends well beyond the immediacy of the plot to become an investigation of the mall-form itself: “Few forms have been so distinctively American, and late-capitalist, as this innovation, whose emergence can be dated: 1956; whose relationship to the well known decay-of-the-inner-city-rise-of-the-suburb is palpable, if variable; whose genealogy now opens up a physical and spatial prehistory of shopping in a way that was previously inconceivable; and whose spread all over the world can serve as something of an epidemiological map of Americanization, or postmodernization, or globalization.” (5)

The mall-form embodies the potential commodification of everything. Malls are dazzling temples for the worship and adoration of an abstract and universal form of labour power, today alienated, objectified, subsumed at the global level, and made somewhat invisible by machinic and thus potentially self-perpetuating production/consumption processes: “In the social system reduced to the pure representation of the law of circulation, productive circulation annihilates itself in pure motion. The social pendulum beats indefinitely.” (6) Until, that is, the worker citizens - the zombies - rise up. Thus, an allegorical formula for Dawn of the Dead might go something like this:

Blood = money, extracted surplus value, capital.

Mall = commodities, the city, dead labour.

Zombies = Marx’s (lumpen-)proletariat, a potential revolutionary force.

In contemporary post-Fordist conditions the ongoing tendency towards proletariatisation - as theorised by Marx - no longer develops solely in “factories,” and thus is not composed solely of and by industrial workers. Rather, today proletariatisation is developing in a glocalised “social factory,” one composed of and by workers, non-workers, unemployed workers, and unemployable workers. Hence, any distinction between the proletariat and the lumpenproletariat collapses, as does any historical sense of the types of political agency this new proletariat might adopt. Yet the problems of decision and organisation remain. If in Dawn of the Dead the zombies are a jacquerie or mob - one embodying the first sparks of revolution - it is in Romero’s later movie Land of the Dead (2005) where the zombies begin to develop organisational cohesion and strategy.

Famously, when Marx and Engels began the Manifesto of the Communist Party with the words “A specter is haunting Europe” they invoked what Antonio Negri describes as a “positive ghost,” that is to say, an amazing opposition to the “powerful ones, the masters, the privileged, the heirs” of accumulated wealth and the Rights of the City. (7) Today Negri is exemplary in tracking a genealogy of this spectral-yet-real force; from pre-modern peasant uprisings, proletariat insurgencies and communist movements to twentieth century anti-imperialist and anti-colonial struggles, all the way into the contemporary world, where, he observes, this oppositional movement has been completely jammed by the new “Power of command” of a global Empire. And in this far more “tragic” scenario, Marx and Engels’ specter transforms into something truly monstrous and vast: “If there are no longer specters but rising giants, then violence, destruction and creation, corruption and generation close ranks all around us … We don’t know what will happen.” (8) Within this new bio-political monster, Negri affirms, stirs an insubordinate collective subjectivity, a virtual “full life,” the “inside” of a productive transformation capable of sustaining a positive “to come,” that is to say, of creating - and continually recreating - the common. What the hell is it? - It’s us!

As more and more of humanity migrated to the city - and to monstrous effect - so too more and more of the city migrated elsewhere. Today the smoother spaces and territories of the nomads and tribal peoples have been captured in entirety by Empire, hybridized with the striated spaces of settled peoples, city dwellers: a networked, multidirectional glocal space is now fully operational: “There is something that in the microcosm repeats the macro, that penetrates the singular being and that traverses multiplicity.” (9) And yet from inside this hazardous multiplicity of microcosmic (glocal) non-places, ones monitored, controlled, and policed by a new urban Order - here on a swarming “planet of slums” (10) - the biopolitical monster Negri names the multitudo is rising, inventing new and “real places,” giving fresh “materiality to time and space, to struggle and decision.” (11)

In the great ethical writing machine that is A Thousand Plateaus, Deleuze and Guattari say similar things: “The smooth spaces arising from the city are not only those of worldwide organization, but also of a counterattack combining the smooth and the holely and turning back against the town: sprawling, temporary, shifting shantytowns of nomads and cave dwellers, scrap metal and fabric, patchwork, to which striations of money, work, or housing are no longer even relevant. An explosive misery secreted by the city…” (12)

Misery, poverty, monstrosity… What positivity might be gained within the wrecked confines and vast suffering of these conditions? What galvanising organisational energy might be tapped for creating ways out from here? To affirm the possibility of a city born of misery is to be against contemporary forms of accumulation. To affirm the possibility of a time born of poverty is to be against corruption. (13) To affirm the possibility of a new earth born of monstrosity is to be against capitalist measure and control. This three-fold being-against gives ontological force to my title: Sub-Urbanism consists in the negation of the negation that is today’s Über-Urbanism. Sub-urbanist thought and action works towards constructing a passage through and beyond the often terrifying realities of the contemporary city.

By the final pages of Italo Calvino’s novel Invisible Cities, the young Venetian traveler Marco Polo and his friend Kublai Khan, emperor of the Tartars, have talked their way through a labyrinth of myriad imaginary cities and are now discussing what the Great Khan refers to as the “infernal city,” “the last landing place” towards which the current is drawing all of us closer and closer. Polo disagrees, claiming that “the inferno” is not our destiny but rather where we’re already at, “where we live every day, that we form by being together.” “There are two ways to escape suffering it,” he says, “The first is easy for many: accept the inferno and become such a part of it that you can no longer see it. The second is risky and demands constant vigilance and apprehension: seek and learn to recognise who and what, in the midst of the inferno, are not inferno, then make them endure, give them space.” (14)

Ralph Paine

(1) See Manuel De Landa, A Thousand Years of Nonlinear History (New York: Zone Books, 1997) p. 27. Doubtless the mineralisations of matter which compose the urban “exoskeleton” should themselves be regarded as flows, with the term “mineralization” here signifying an extreme slowing down relative to other faster flows, temporal phases, cycles, speeds, accelerations, and rhythms.

(2) Lewis Mumford, The City in History: Its Origins, Its Transformations, and Its Prospects (London and New York: Penguin, 1966) p. 15, emphasis added.

(3) Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari, A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia, trans. B. Massumi (Minneapolis and London: University of Minnesota Press, 1987) p. 425.

(4) Georges Didi-Huberman, “People Exposed, People as Extras,” in Radical Philosophy 156 (Jul/Aug 2009) p. 17.

(5) Fredric Jameson, “Future City,” in New Left Review 21 (May/June 2003) p. 69.

(6) Isabelle Stengers and Didier Gille, “Time and Representation” in Isabelle Stengers, Power and Invention: Situating Science, trans. P. Bains (Minneapolis and London: University of Minnesota Press, 1997) p. 212.

(7) Antonio Negri, “The Political Monster: Power and Naked Life,” trans. M. Boscagli, in Cesare Casarino and Antonio Negri, In Praise of the Common: A Conversation on Philosophy and Politics (Minneapolis and London: University of Minnesota Press, 2008) p. 200.

(8) Ibid, p. 201.

(9) Ibid, p. 215.

(10) See Mike Davis, Planet of Slums (London and New York: Verso, 2006).

(11) Negri, p. 218.

(12) Deleuze and Guattari, p. 481.

(13) Corruption: the neo-liberal promotion of individual choice (privatization); the managed exploitation of cooperative labour; the linguistic and visual debasements of ideology; and, a complete lack of any resonance between value and being. See Michael Hardt and Antonio Negri, Empire (Cambridge, MA and London: Harvard University Press, 2000) pp. 201 - 3 & 389 - 92. For Negri’s ontology of poverty see Antonio Negri, “Kairos, Alma Venus, Multitudo,” in Time for Revolution, trans. Matteo Mandarini (London and New York: Continuum, 2004). And further on poverty, some crucial and wonderful remarks by Alexander García Düttmann on Walter Benjamin’s 1933 essay Experience and Poverty: “Walter Benjamin makes a distinction between a ‘new misery’ that came into being after the First World War because of the ‘tremendous development of technology,’ and a ‘great poverty,’ whose ‘face is of the same sharpness and precision as that of a beggar in the Middle Ages.’ According to Benjamin, there is a revealing ‘underside’ to the new misery he detects: the ‘oppressive wealth of ideas’ that doesn’t require a ‘genuine revival’ but instead brings about a ‘galvanization,’ a fixation of the mind. We therefore need to turn against this new misery and to give ourselves completely to the ‘poverty of experience’ that partakes in the ‘great poverty.’ ‘This should not be understood to mean that people are longing for new experience. No, they long to free themselves from experience, they long for a world in which they can make such pure and decided use of their poverty - their outer poverty and ultimately their inner poverty - that it will lead them to something respectable.’ Benjamin advocates a wealth that we can only take in if we ‘give ourselves without reserve’ to poverty; if we transform poverty’s wall into a way (out) as opposed to trying to escape poverty through fake abundance, something that would only serve to render the new misery eternal.” Alexander García Düttmann, “Making Poverty Visible - Three Theses,” trans. A. De Boever, in Parrhesia: A Journal of Critical Philosophy 4 (2008) pp. 6 - 7.

(14) Italo Calvino, Invisible Cities, trans. William Weaver (London: Vintage, 1997) p. 165.

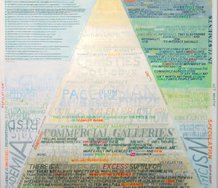

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects Advertising in this column

Advertising in this column

This Discussion has 0 comments.

Comment

Participate

Register to Participate.

Sign in

Sign in to an existing account.