Andrew Paul Wood – 29 March, 2017

I think Shrigley's cartoon drawings are his best work - surreal, absurd, anxious, occasionally outright nihilistic, but always hilarious. These, selected from an archive of around a thousand made between 2004 and 2014, are served up as inkjet prints, which feels a little cheap and somehow inauthentic in some ways, but on another level, is entirely the Shrigley aesthetic. I'm not sure that's obvious to the punter off the street who has paid to come in, however.

Christchurch

David Shrigley

Lose Your Mind

11 March - 27 May 2017

Brighton-based David Shrigley, born in Macclesfield in 1968, was a mite too early and far from Goldsmiths to be one of the YBAs (who, now in middle age, should probably be called MBAs). He graduated from the Glasgow School of Art in 1991 and his art seems a natural extension of the ‘90s self-sabotaging slacker ethos and pop-shock cynicism.

His publically best known work is probably Really Good, the ten-metre-high “thumbs up” currently on the “empty” fourth plinth in Trafalgar Square in London (the Guardian‘s Jonathan Jones liked it, which should always be a cause for concern). He is a (st)ar-tist. He even directed the music video for Blur’s “Good Song”. He has made cartoons for the Guardian and collaborated on the 2007 album Worried Noodles where David Byrne and Franz Ferdinand used his writings as lyrics. There is a strong, sulphurous whiff of Cool Britannia - admittedly an externally imposed condition.

It’s great that his British Council survey exhibition Lose Your Mind is in Christchurch at CoCA, having come from Seoul, South Korea, on its tour. Parts of it delighted me greatly. I think Shrigley’s cartoon drawings are his best work (and I suspect he thinks so too) - Saul Steinberg on acid, a bit of Raymond Pettibon here, a little Beavis and Butthead there, a sort of Manuel Ocampo of the north - surreal, absurd, anxious, occasionally outright nihilistic, but always hilarious. These, selected from an archive of around a thousand made between 2004 and 2014, are served up as inkjet prints, which feels a little cheap and somehow inauthentic in some ways, but on another level, is entirely the Shrigley aesthetic. I’m not sure that’s obvious to the punter off the street who has paid to come in, however.

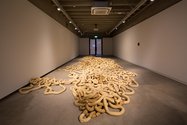

The same can be said for Insects, the sculptures that seem to literalise the spikey black artefacts of the drawings assembled as three dimensional critters. There is the well-known, deliberately clumsy over-literal metaphor of Death Gate - a metal gate formed from the word “death” repeated. There is Beginning, Middle and End (2009), 2000kg of clay formed into the mother of all Ocampo-esqe extended turds by (as with many Shrigley works) an army of volunteers. There are the repetitive Boots, the crudely formed eggs like a showdown on Twitter, and the headless, stuffed Ostrich (2009, the largest of his taxidermies). There is Cheers (2007), a pair of fishing waders filled with expanding foam that holds them upright as if worn by someone’s bottom half.

It’s all so confrontationally half-arsed and primed to fail or fall short in some way - bad art, but that’s the point, or was the point - the desire to completely sabotage the purity of white gallery cubes and slick expectations of 1980s commodity art. Are we supposed to laugh with it or feel some kind of pity? Bathos or pathos? That’s all part of the enigma. There’s an element of sublimated camp to it and as Susan Sontag said of camp: “Camp taste turns its back on the good-bad axis of ordinary aesthetic judgment. Camp doesn’t reverse things. It doesn’t argue that the good is bad, or that bad is good. What it does is to offer for art (and life) a different - a supplementary - set of standards.” Or is it all falling apart because the world (or at least the part that designates itself “Western”) is falling apart?

The most engaging work in the show, and probably the key that unlocks a lot about Shrigley‘s artistic philosophy, is The Artist, a robot disguised as a squashed, blank-eyed head with a couple of felt-tips up its nose. As it follows the apparently random path of its programming, it mechanically, mindlessly traces out some beautiful drawing. Is Shrigley telling us something about his own insecurity about his processes, or is it a consciously literal interpretation of the Duchamp quote, “In France there is an old saying, ‘stupid like a painter’”? It nicely sums up the superficial appearance of low-stakes disposability that subverted the assumptions of the artworld and punctured the neo-Dada, neo-Situationist wankery in the 2000s.

But still, these days it looks a little dated. All of its lessons were thoroughly digested one or two generations ago. The shenanigans no longer have the freshness and shock value that once propelled Shrigley within touching distance of the Turner Prize in 2013. He has been anointed by the British Council. The slacker subtopian aesthetic gives Gen X-ers like me a nostalgic thrill, but it has lost its Situationist context to a certain extent. It has, despite its mordant sharpness of wit and bleak brilliance, quelle horreur, become establishment.

On the other hand, in these farcical times of Brexit and Trump, the work has a whole new, and possibly even more relevant context to be deliciously awful in.

This is the art we deserve.

Andrew Paul Wood

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects Advertising in this column

Advertising in this column

This Discussion has 0 comments.

Comment

Participate

Register to Participate.

Sign in

Sign in to an existing account.