Warren Feeney – 10 March, 2017

'Mayfield Residence' looks like an exhibition that could only have come from rural New Zealand; The Social's critique of such material was as astute as it was respectful. In doing so, the participating artists fulfilled an important objective that all public galleries seek to address; nurturing and cultivating the identity and sense of place of the district and people that they are part of - and educating and challenging them.

Ashburton Art Gallery

The Social (Hana Aoake, Audrey Baldwin, Sandrine Castel, Motoko Kikkawa, Dave Marshall, Lucy Matthews, Adrienne Millwood, Gaby Montejo and Matthew Ward)

Mayfield Residence

26 February- 19 March 2017

Responding to an informal invitation from the Ashburton Art Gallery in 2015 to contribute to its exhibition programme, the artist collective, The Social, came back to the gallery with a proposal to visit the township of Mayfield in mid-Canterbury for an exhibition of works assembled from objects in the town’s op shop, Overflow Retro.

Mayfield Residence opened 25th February, less than a week after the nine artists from The Social, (Hana Aoake, Audrey Baldwin, Sandrine Castel, Motoko Kikkawa, Dave Marshall, Lucy Matthews, Adrienne Millwood, Gaby Montejo and Matthew Ward), visited to select items of their choice for installation in the public gallery. Yet, it is not just the pace at which Mayfield Residence has been conceived and delivered that impresses, but also how, after five years and more than forty-five arts projects in public spaces, The Social‘s guiding ambitions for purposeful and sincere social engagement have been so comprehensively realised - ironically, in the white cube space of an art gallery.

However, it has to be acknowledged that The Social was working with great source material. I only discovered Overflow Retro because of Mayfield Residence, but apparently it has cult status as the op shop to make pilgrimages to. Opened eighteen years ago by mid-Canterbury resident Jan Howden it was recently described by Canterbury’s lifestyle magazine Latitude as overflowing with treasures; Crown Lynn crockery, Victoriana books and statues, a surprising selection of machinery and tools, fabrics, domestic ware and toys. As an artist collective, committed to engaging the public, ‘in a way that is meaningful, relevant and fun; [and] encouraging art to live and breathe outside of its usual context,’ (1) The Social’s partnering with Overflow Retro could not have been more fitting.

The Social was founded in 2012 by Audrey Baldwin, Rosie Fenton, Rosalee Jenkins, Lucy Matthews, Gaby Montejo, Gareth Talbot and Alex Wotton as an artist collective, to ‘stimulate conversations about art between artists and the wider community.’ For at least its first two years its attention was on Christchurch and its vacated inner-city spaces. Most famously, it gained public attention in December 2012 with curator Jamie Hanton’s and photographer Alex Lovell-Smith’s The Loss Adjusters, a bogus public assessment agency for loss in whatever form, that may be, for Christchurch residents. Hanton and Lovell-Smith set up a make-shift office in Christchurch’s temporary shopping precinct Re:Start. The Loss Adjusters responded to The Social’s three founding principles: (a) it took place outside the space of a gallery; (b) it was frugal in its use of resources; and (c) it was socially engaged and about things perceived to be outside of the domain of the art world.(2)

As a check list of principles, Mayfield Residence ticked all the boxes, even in spite of the use of a gallery space. The working processes for the ideas realised in the exhibitions were developed in the retail and community space of Overflow Retro in a rural township 35 kilometres from Ashburton (population 200), with the nine artists working with groups and individuals not usually occupied with the art world. The artists collaborated and assisted each other in the construction of work, and, not-withstanding a couple of airline flights, it was an arts project delivered with an appropriate frugality. All items selected for the exhibition were kindly loaned by Howden, to be returned when Mayfield Residence is de-installed.

The direct involvement and support of the op shop and staff, in itself, is enough to confirm that, in principle, this project was among The Social‘s most successfully realised. Inspirational and admirable as their agenda for the arts has been, its commitment to financial restraint, and often an accompanying modesty of scale for works in public spaces, predominantly in the construction site and environment of central Christchurch, has made the delivery of its primary purpose often a demanding and sometimes even impossible task.

At times, such challenges have been hindered by seeking to activate vacant sites without the necessary accompanying resources for community engagement. For example: Daegan Wells’ Wetlands in February 2014, in which decoy ducks were positioned -floating in pools of water at various inner city locations - was essentially overwhelmed by the unwelcoming surroundings and demolition sites that Wetlands sought to occupy.

Mayfield Residence felt like a step up, not simply because of the exchange of conversations between the artists and the mid-Canterbury community, but also because of The Social’s use of a public gallery exhibition space. Removed from the cacophony and distraction of industrial and commercial reconstruction, Mayfield Residence highlighted the merits of the white cube as a community space for contemplation, reflection, discussion and social engagement. As such, it also drew attention to the important need for a diversity of opportunities for serious artists to conceive and present work in the public arena that tested, extended and grew their practice. Whether a public gallery, artist-run space, commercial gallery or temporary building site, it is difficult to believe that Mayfield Residence could have been conceived and delivered without the kind of field work and diversity of public engagement that occurred prior to the Ashburton exhibition. That is, Mayfield Residence raised the question as to why public galleries throughout New Zealand do not commit to demarcating recurring space in their annual programme for such proposals from aspiring artists and collectives.

There was a lot to like about Mayfield Residence: The alliance with found-objects connected to the history of the community that they had come from - predominantly rural, white middle-class homes - and was the subject of a thoughtful and cohesive body of work in an exhibition that was respectful, playful and affectionate towards its content - without losing its sense of critical insight or aesthetic judgment. Look no further than Audrey Baldwin’s positioning of domestic ware and ornamental pairs of animals; cows, goldfish and pink poodles on a pale blue and pink ladder, or Lucy Matthew’s floating piano roll music sheets suspended from the centre of the gallery ceiling.

And their contributions were complemented by, possibly the most economically conceived immersive experience ever to find itself in a gallery: Sandrine Castel’s climb-inside tent of coloured umbrellas and crocheted blankets, and Matthew Ward, Motoko Kikkawa and Dave Marshall bright-red children’s car with its own road video. It was a playful work, yet deceptive in its promises of nostalgia with its video, shifting between racing down a country road and the details of dumped and corroding metals and materials.

A wall relief and sculptural work by Adrienne Millwood personalised the idea of public responsibility, bringing together primary school drawings and pages from writing exercise books with an appropriate evocative nostalgia, and playing them off against an aerial map of irrigation channels that was suspended from the ceiling, casting shadows on the gallery wall.

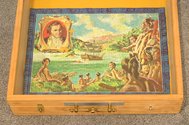

Hana Aoake’s grouping of a jigsaw puzzle of Cook’s arrival in New Zealand, with Air New Zealand’s trademark Hei-Tiki, a British flag, photographs of the Napier earthquakes and a photograph of Queen Elizabeth’s II coronation in 1953 acted like an awkward memory from childhood; the familiarity of objects from shared past experiences and remembered uncertainty about their co-existence.

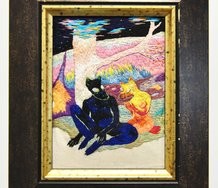

Gaby Montejo contributed two works that looked like a pairing of unanticipated companions that were just waiting to spend time with one another: A seemingly insecurely positioned wheelbarrow, brimming to the top and on all sides with mannequins and statues (that includes Shrek and St Joseph); and his consideration and arrangement of a 1950s stereogram, fresh fruit and picture books - it might sound predictably absurd and Dadaist - that made perfect visual sense.

Mayfield Residence looks like an exhibition that could only have come from rural New Zealand; The Social‘s critique of such material was as astute as it was respectful. In doing so, the participating artists fulfilled an important objective that all public galleries seek to address; nurturing and cultivating the identity and sense of place of the district and people that they are part of - and educating and challenging them. On this occasion, the Ashburton Art Gallery has given support and voice, not only to an artist’s collective that has risen to the opportunity, but also to an exhibition that seeks to provide genuine and meaningful engagement with its communities.

Warren Feeney

(1) Lucy Matthews, Audrey Baldwin, Rosalee Jenkins and Gaby Montejo, [eds], The Social Artist Collective. Projects November 2012 - September 2013, Christchurch: BNS Design & Print, 2016, p. 7

(2) Ibid, pp. 5 - 6

Advertising in this column

Advertising in this column Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

This Discussion has 0 comments.

Comment

Participate

Register to Participate.

Sign in

Sign in to an existing account.