Peter Dornauf – 19 August, 2017

Work is put up on walls then taken down and nothing much else happens. It's a bit of a desultory business. Where can public endorsement reside? Short of putting a comment book next to the piece, no one is any wiser. Unless of course the work just happens to be interactive, or even better, looks as if it might be.

Hamilton

Selected finalists

National Contemporry Art Award

Curated by Elizabeth Caldwell

29 July - 5 November2017

How does any artist ever know if their work has done its job? How can they know if it has made its point, arrested attention or moved the punter in any intellectual or emotional way? Unless one of those gallery visitors communicates directly with the artist, such knowledge is lost, stays private, remains forever unknown.

Work is put up on walls then taken down and nothing much else happens. It’s a bit of a desultory business. Where can public endorsement reside? Short of putting a comment book next to the piece, no one is any wiser. Unless of course the work just happens to be interactive, or even better, looks as if it might be.

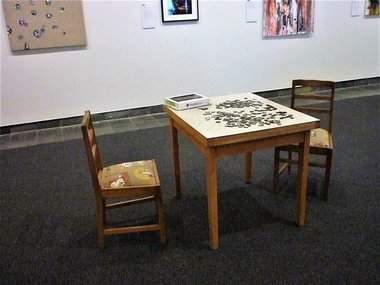

There was one such piece (of the fifty included) in the National Contemporary Art Award currently running at the Waikato Museum. Curated by Elizabeth Caldwell, director of City Gallery, she included a work that was part sculptural, part installation and part readymade, consisting of an old, small Formica dining-room table with two chairs of the same vintage. The chairs seemed newly upholstered, their seating covered in a fabric that displayed a decorative pattern depicting sweet playful kittens. Into this dated but charming domestic scene was placed, on the table, an empty jigsaw box with its contents spilled out across the pale coloured Formica.

The work by Tiger Murdoch was entitled Great North Road. He had purpose-built a jigsaw that depicted an empty New Zealand state house. The complete image of the house was portrayed on the box. No detailed exegesis of such a piece is necessary here. It worked on many levels.

There was no sign or notice on the wall or next to the art work saying, ‘Please handle, take a seat, try putting the pieces together, help yourself.’ But people were. They sat down at the table and proceeded to play.

Now all this might just demonstrate the gauche nature of provincial punters, ignorant of the procedural rules of art gallery attendance, who boldly went where no self-respecting gallery visitor would go. Or it might alternatively show that the work arrested attention and was compelling enough for visitors to ignore the usual gallery protocols and engage with it directly.

In any case the artist should be gratified.

Was all this simply instinctive, or had the visitors read the blurb about the question of the housing crisis, the growing culture of inequality in the country and the clever link with the use of 1930’s post-Depression period style furniture? Perhaps it doesn’t matter. The work didn’t win the prize but it did win the public.

The $20,000 prize went to an abstract painting whose title explored the same territory, generically speaking. Called The Meaning of Ethics, its scribbled notations were similar to the work of Cy Twombly. Subtle workings with the colour mauve were involved, but it was the large empty spaces daringly left around the central abstract forms that provided the artwork with a certain authority and power.

Ethical questions were canvassed by a number of other artists in the show too. Luise Fong made some observations about urban existence versus the natural enclaves associated with the native bush in her mixed media work Only Love Can Hurt Like This. Judith Lawson’s See, Look, Sea focused on environmental concerns, while Mark Purdon commented on the notion of identity and non-place in corporate space.

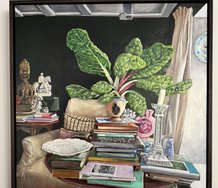

Of the fifty works selected, a third were paintings; it’s good to see that that side of things is alive and well. Those that stood out included Robyn Gibson’s The Artists’s Encumbrance, which depicted, in a Philip Guston sort of way, the artist’s own little angsts. In View, Sarah Smith was inspired by the landscape of the Manukau Harbour, presenting a powerful black and white abstracted image (using acrylic, ink and resin) reminsicent of Franz Kline. Such abstract expressionism was also apparent in Sue Reidy’s Transmuting the Improbable, where all the painterly mark-making tricks that belonged to that genre were effectively manipulated.

A quieter more muted version of the same trope was Red House by Frances Rood, an engaging small work on paper, perfectly modulated, that played with ideas and forms suggestive of architectural floor plans, while the floating geometric and biomorphic configurations that formed the talisman-like blobs of In the Place of Totems by Julien Dyne, provided another aesthetic twist to the abstract repertoire on display.

Of the photographs, Purdom’s Gas Station, an extension of Hopper and Ruscha, was particularly striking, as was the inkjet print of Stuart Forsyth that ironically used discarded adhesive vinyl found in past exhibition lettering and suitably named Leftovers Reconfigured.

The sculptural pieces used a variety of innovative means too. Vonney Ball’s Settled in the Soil spoke of the perennial theme of colonization, using cattle bones displayed on a table. Made of white ceramic and covered in rose prints, they became in the process, a metaphor for English crockery—with all the political undertones that that carries.

Place and displacement was also explored by Mel Ford who found core drill samples of discarded bricks linked to the railway tunnel near Paekakariki. These he arranged in grids to create patterns of formal abstract elements. Such reconstruction from castoff materials was also exploited in Chrysalid by Sebastien Jaunas, where piano mechanisms, along with paper, plastic and wood, were reconfigured to look like a flayed carcase.

Something of the same collaging procedure was also found in Gemma Baldock’s jerry-rigged piece, Presentation Porker. Here she employed what resembled paper doll type cut-outs, echoes of Gavin Hurley, to construct a tableau of characters depicting an event in a Southland suburb.

One has to say, job well done, which is where we came in, to all those artists reinventing and reworking diverse artistic tropes for an astute contemporary audience.

Peter Dornauf

Advertising in this column

Advertising in this column Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

This Discussion has 0 comments.

Comment

Participate

Register to Participate.

Sign in

Sign in to an existing account.