– 17 August, 2017

This is Knox's third exhibition of cigarette butt sculptures: the first made in gold and discarded in to the street; and another carved from human finger bone, also shown at Robert Heald Gallery. Prior to smoking, for Knox a cigarette is like the perfect little modernist sculpture, which, once stubbed, becomes a twisting baroque sculpture. An aesthetic shift which turns back time.

I’ve been reflecting on death and the act of smoking lately—though not over a cigarette, mind you. Tauhou, John Ward Knox’s recent exhibition at Robert Heald Gallery, reflects a shared fascination with the symbolically charged cigarette, the contested terrain they occupy, and the complex rituals of their consumption.

Material traces of smoking litter the show. In part, the exhibition acts as an apparent trace of moments passed: a smoke and a conversation shared, stubbed, left lying on the table and carried away on the wind.

The exhibition is comprised of four main bodies of work which summon a range of interconnected associations. Central to the exhibition’s operation is an interplay between materials and forms considered precious and others considered commonplace. This interplay is also connected to a tension between the found and the fabricated. Knox’s subtle sculptural gestures gently problematise easy evaluations, drawing attention to the unlikely objects, moments and rituals we attribute meaning and value. Habits (i-vi), for example, feature intricately carved matchstick forms in woolly mammoth ivory, convincing illusions executed to scale and with perfectly blackened ends.

Writing for National Geographic, Jani Actman notes:

For 20,000 years the remains of millions of woolly mammoths remained locked in permafrost in Siberia and elsewhere-until recently. Warming temperatures have melted this icy layer, bringing their valuable ivory teeth within grasp and leading to a burgeoning trade.

For several years conservationists have said this trade is hurting mammoths’ modern-day relatives: African elephants, which face a poaching crisis. The international trade in elephant ivory has been banned since 1990, but smugglers try to get away with selling elephant ivory by claiming it’s legal mammoth ivory, which looks nearly identical to the untrained eye.

To employ this as a sculptural material is to conjure extinctions past and future: valuable bones unearthed by anthropogenic climate change, the very forces which now threaten to extinguish their African elephant relatives, alongside the human species.

Knox’s matchstick forms are complemented with meticulous paua shell carvings of tailor-made cigarette butts. The paua featured in the exhibition was sourced on the beach metres from the artist’s current residence in Karitane, Dunedin. Knox’s use of paua as a material evokes its role in traditional Māori art, particularly the iridescent eyes of carved figures. Though viewers might also connect paua with the ubiquitous commodification of Māori culture—commercially produced tourist souvenirs in particular—Knox’s multivalent work maintains an elusiveness where this association exists within a wider web of possibilities. Habits (vi) co-opts the common practice of using paua shells as ashtrays, comprising a found paua shell vessel for a set of carved paua cigarette butts nestled inside. While sourcing a local material, Knox also problematises a local vernacular.

This is Knox’s third exhibition of cigarette butt sculptures: the first made in gold and discarded in to the street; and another carved from human finger bone, also shown at Robert Heald Gallery. Prior to smoking, for Knox a cigarette is like the perfect little modernist sculpture, which, once stubbed, becomes a twisting baroque sculpture (1). An aesthetic shift which turns back time.

Habits (iv) consists of two pill forms: one in paua, another in pearl. The former is reminiscent of the elongated shape of a ‘big pharma’ tablet. Paracetamol perhaps, or something stronger, a seductive looking ‘pain killer’ with perfectly rounded edges. The white pearl pill could easily be something similar, yet it also suggests a pharmaceutical or illegal psychoactive drug. Who knows, of course, it is their ambiguity which provides the charge.

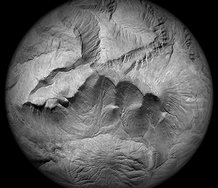

Humours are human eye ball sculptures carved from woolly mammoth ivory, mussel shell and glass, with a touch of saffron for the veins. They lie disembodied on a delicately balanced table and stare back at viewers, looking at us looking. We might read them as a reminder of human mortality and the ephemeral nature of life, just as a skull might in a vanitas painting, perhaps accompanied by a candle, pipe and assortment of fruit.

The exhibition title Tauhou, an eponymous sculpture within the show, was dictated by chance (2). A silvereye bird (Zosterops lateralis) flew in to a glass window at Knox’s home, where it subsequently died on the table in front of him. The artist preserved the bird and replaced its eyes with castings of 18 carat gold. The silvereye is now forever at rest, lying flat atop a fabricated timber trestle table, recycling what appears to be an old painted fence. The silvereye is surrounded by a scattering of sesame seed forms— rapid prototyped and then cast in sterling silver—evoking a funeral display, memorial or ‘still life’.

The silvereye is a small bird native to the Pacific Southwest. It is apparently self-introduced to Aotearoa, and protected as a native New Zealand species. The Māori name ‘Tauhou’ refers to the arrival of the bird in Aotearoa. Though there were specimens of silvereye already in New Zealand, the common wisdom is that a migrating flock was blown over from Australia in a storm shortly after the arrival of Europeans. In more general terms, the Māori name can also mean strange, new, unacquainted, exotic and unfamiliar. In this sense, the Tauhou’s history could be read as a poetic postcolonial metaphor.

In more oblique territory, Notes is a suite of carved wooden tablets with ambiguous pictographic markings carved in to their surfaces. They are made from Bubinga, a popular imported African hardwood often used in fine furniture and cabinetry. The tablets’ small size, bevelled edges and polished finish make them highly tactile objects. They are designed to be held or carried in one’s pocket, a refreshing user experience for contemporary art.

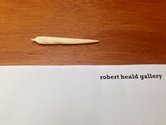

Though these collective works might evoke contemporary memento mori, in a kind of coda or counterpoint, the exhibition also features a small sculpture of a cannabis joint. It is untitled, carved to scale from woolly mammoth ivory, and though not officially part of the show, is a loaded object placed knowingly next to the fresh cut lilies on Heald’s minimalist desk. The ‘jazz cigarette’ might suggest a kind of playful lightness, a degree of levity in response to the more sombre associations suggested by the exhibition, from mortality and the ‘death drive’ to the troubled legacies of colonisation and the peril of burning fossil fuels.

Like art, cigarettes retain a function as currency given their symbolic power and increasing market value. Whatever their contents, both act as delivery systems for altered states of perception. In this light, perhaps the exhibition also suggests that art can help us get to a higher place.

Emil McAvoy

(1) John Ward Knox, email message to the author, 4 July 2017.

(2) Ibid.

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects Advertising in this column

Advertising in this column

This Discussion has 0 comments.

Comment

Participate

Register to Participate.

Sign in

Sign in to an existing account.