– 17 January, 2018

'Limits to Growth' presented an ecology of art works in which rigorous research was applied to precise sculptural and filmic gestures. These works were often constructed from, and concerned with, ancient materials and natural resources. The artist also drew on his upbringing within a mining family as raw material.

Pay Dirt: Energy, Extraction & Expenditure in Nicholas Mangan’s Limits to Growth

we mine not with shovel yet the production of our currency draws on the bowels of the earth…

- An excerpt from a video work within Nicholas Mangan’s Limits to Growth

Mining the conceptual foundations of Nicholas Mangan’s Limits to Growth revealed a seam of glimmering ideas. The Dowse Museum exhibition brought together a collection of recent works by the Australian artist in a complex layering of economic, environmental and geopolitical subjects. The show was Mangan’s first survey to be held in Aotearoa, and was jointly developed by Monash University Museum of Art in Melbourne, the Institute of Modern Art in Brisbane, and KW Institute of Art in Berlin, alongside an associated publication. The introductory wall text frames the terrain:

The importance of analysing colonial exploitation, global capitalism and resource extraction, of rethinking and responding to historical examples, has never been more relevant. Prying open these existing narratives and events, Mangan provides a space in which to project forward into the future.

The exhibition title referenced an eponymous 1972 report commissioned by the Club of Rome and funded by Volkswagen: an example of early systems dynamics, computer modelling the impact of exponential economic and population growth on the Earth’s finite natural resources. During his artist talk, Mangan noted that they got the precise computer modelling wrong; its predictions were nonetheless disconcerting, evidenced by the climate change and environmental degradation characteristic of our age. Further, the devastating implications of ‘business as usual’ were made painfully ironic by Volkswagen’s own recent involvement in dieselgate.

Limits to Growth presented an ecology of art works in which rigorous research was applied to precise sculptural and filmic gestures. These works were often constructed from, and concerned with, ancient materials and natural resources. The artist also drew on his upbringing within a mining family as raw material.

Leading the exhibition was a project investigating aspects of the Micronesian island of Nauru, incorporating a number of art works which address Australia’s role in the Pacific. Nauru: Notes from a Cretaceous World (2009-2010), a single-channel video, was first inspired by Mangan’s fascination with Nauru House, a landmark building in Melbourne constructed in the 1970s by the Republic of Nauru, a symbol of its new-found wealth funded with proceeds from its lucrative phosphate mining.

It was the large, sombre stones installed in the forecourt that caught Mangan’s attention. These ancient stones—decomposed marine life and bird excrement compressed over millions of years—were formed in to pinnacles during the cretaceous period, the limestone rich in phosphate. The initial strip mining was done by Australia, with further connections to New Zealand in its use of phosphate fertilizer in farming to feed the British Empire. Transported from Nauru and installed as trophies, the stones appeared somewhat alien.

During the late 1960s and early 1970s, Nauru had the highest per-capita income of any sovereign state in the world, following its independence from Australia, New Zealand and Britain in 1968. After the extraction and depletion of its natural mineral resources, alongside corruption and mismanagement, the state went bankrupt and the stones removed when it subsequently sold the building.

Combining location footage and archival material, the video poetically detailed the artist’s trip to Nauru to further investigate this history, and is narrated by him. Viewers will also know the island through the media attention generated by its role as an offshore immigration detention centre for ‘boat people’ seeking refuge or asylum in Australia; a centre where alleged human rights abuses have occurred for years and attracted ongoing international condemnation.

Following Nauru’s bankruptcy, it became a tax haven and illegal money laundering centre, and is now heavily dependent on Australia for aid, a context which frames its current situation. This situation is addressed in the narration of the film with the centre itself conspicuously absent. Archival shots of the stones in chains outside Nauru House read as a further allusion to this, alongside other forms of colonialism. Haunting footage of a local bird tied to the top of a cage drove this feeling home.

The video projection was also complemented by Pacific Sediment (2010) a custom-made vitrine containing printed archival research material on the subject, and a sprinkling of small limestone rocks. It was also flanked by a sculpture, Dowiyogo’s Ancient Coral Coffee Table (2009-10). Then president, Bernard Dowiyogo, provocatively proposed the last remaining stone pinnacles be turned in to ancient coral coffee tables and sold on the international market. In response, Mangan traced the Nauru House stones to the residence a former employee and convinced them to let him purchase a section. The artist then sliced in to the rock, a process which he describes as opening up a deeper narrative. The resulting three coffee table sculptures may indeed be sad monuments as the artist suggests, yet they also retain their sharp edges.

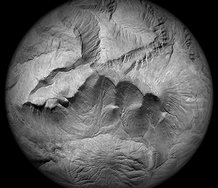

In A World Undone (2012), a silent video that was part of a wider project, the artist sourced and dispersed zircon—Earth’s earliest formed mineral 4.4 billion years ago—within sandstone mined from the Jack Hills in Western Australia and purchased from ebay. Mangan built a dust chamber in which to smash the sandstone and struck it with a geologist’s hammer given to him by his grandfather, a former mine director. He was granted access to a high-speed camera used to study the impact of simulated car crashes, and recorded the resulting dust cloud at an extremely high frame rate. The particles glisten like swirling galaxies against a black backdrop, echoing the video’s projection in a blacked-out space. The slow motion circulation of dust made the air currents visible as it floated and fell perpetually in space.

Ancient Lights (2015) saw the artist tap in to the Dowse’s existing roof mounted solar panels to power a pair of opposing video projections in real time. Like Nauru: Notes from a Cretaceous World, these video works were front-projected on freestanding wooden screens, complemented by a plywood clad partition at the gallery entrance. The electrical transformer and extensive cabling commanded a presence in the gallery, while transforming the light energy of the sun into the light of the projectors.

The first looping video saw a 10 Peso Mexican coin spinning on a white table in perpetuity, its elliptical shadow oscillating with each turn. Mangan had been reading Georges Bataille’s The Accursed Share and likened its description of ancient Aztec sun worship—and the human sacrifices connected to their cultural anxiety that it would continue to rise each day—to the contemporary sacrifice we continue to make in paying for electricity. As demonstrated by the projection’s solar powered means of display, this sacrifice recurs while other viable renewable alternatives exist.

The second video combined footage from the Laboratory of Tree-Ring Research in Arizona, Texas, where astronomer A.E. Douglass was attempting to find evidence of the eleven-year solar cycle via dendochronology, and images from the Gemasolar plant in Seville, Spain, which claims to be the first 24 hour solar power producer. Here the artist drew on the theories of Russian scientist Alexander Chizhevsky, who contentiously proposed that historical examples of collective human behaviour such as social revolution, insurrection, war and mass migration are triggered by the sun’s effects.

The video featured footage of slowly swivelling solar panels reflecting the sun, the wider panel array and their arid environment. This was intercut with footage of a rotating section of tree filmed from above, its rings spinning like a vinyl record. These were punctuated with flashes of archival imagery and occasional glitchy, buzzing noise.

The exhibition wall text asserted that the work “enables reflection on our global energy demands and highlights the political reluctance that delays shifting power production and consumption towards more sustainable models.” The Hutt City Council installed more solar panels for the show, which will in future power the museum and sell any potential excess back to the grid. How rewarding to see a public gallery walk the “sustainability” talk.

In the Limits to Growth project, Mangan contrasted the mining of the ancient Rai stone currency used on the Micronesian Island of Yap with the digital mining of the cryptocurrency bitcoin. The work comprised of 2 looping single-channel videos displayed on LCD monitors installed back to back in a darkened room, an adjacent suite of framed photographs and a framed archival image.

Mangan described being inspired by the story of a miner working in remote Australia, who as part of his remuneration package received free electricity with his accommodation. Using an internet forum he invited others to utilise his free electricity supply to power a bitcoin mining rig: a server whose computer processing runs complex algorithmic equations which validate other transactions and in turn generate credit in bitcoin, and which requires large amounts of energy to run.

The artist was intrigued by this parasitic relationship and convinced the Monash University Museum of Art to install a custom-built mining rig in their air-conditioned basement, and run on the University’s electricity supply. Mangan used the bitcoin credit generated by the rig to purchase the hand printing of a suite of colour photographs documenting Rai stones, large flat discs of carved limestone whose function as a prototypical virtual currency find an echo in bitcoin’s operations.

The framed photographs sat on the gallery floor and leaned back to back, mimicking the placement of the stone discs documented within them. A small archival image depicting a representative of the Bank of Detroit touching a Rai stone purchased by the bank hung nearby, its oversized white matte the scale of the stone in the photograph.

The first video consisted of underwater footage circling a partially submerged Rai stone on the seabed (they were mined on the neighbouring island of Palau and on occasion fell overboard during transportation), with underwater sounds and the breathing apparatus audible. The second contained footage of the artist’s bitcoin mining rig including the noisy accompanying fans, and featured subtitles which emerged and disappeared from the bottom centre of the screen. Several excerpts read:

we mine not with shovel yet the production of our currency draws on the bowels of the earth…

we must circulate continuously or risk death…

our true value is measured in waste…

we the subjects of obsolescence, discarded, superseded by the desire for acceleration…

we are a finite resource…

In the context of growing yet modest trans-Tasman contemporary art exchange, a show like this was refreshing. The work directly addressed our collective past, present and future—particularly in the wider Asia Pacific region—was meticulously executed, and rewarded further investigation.

Mangan’s research revelled in reflecting the complexities and contradictions of our world: a world in which mythical understandings, old and new technologies, dark histories, utopian ideas, alternative practices, the physical and virtual, systems of value and modes of exchange all coexist. A poetics of late capitalism, perhaps. As humankind pushes against the limits to growth, at times Mangan may reflect a world undone, yet in his work we encounter it coming together at the precise moment it is falling apart.

Emil McAvoy

![Nicholas Mangan, Ancient Lights

(2015) [detail]. Two-channel HD video installation powered with photovoltaic off-grid system: video #1 HD colour, sound, continuous loop (13 mins 41 secs); video #2 colour, silent, continuous loop (5 mins, 12 secs).](/media/thumbs/uploads/2018_01/007_DSC7916_jpg_380x125_q85.jpg)

![Nicholas Mangan, Ancient Lights

(2015) [detail]. Two-channel HD video installation powered with photovoltaic off-grid system: video #1 HD colour, sound, continuous loop (13 mins 41 secs); video #2 colour, silent, continuous loop (5 mins, 12 secs).](/media/thumbs/uploads/2018_01/008_DSC7918_jpg_380x125_q85.jpg)

![Nicholas Mangan, Ancient Lights

(2015) [detail]. Two-channel HD video installation powered with photovoltaic off-grid system: video #1 HD colour, sound, continuous loop (13 mins 41 secs); video #2 colour, silent, continuous loop (5 mins, 12 secs).](/media/thumbs/uploads/2018_01/009_DSC7349_jpg_380x125_q85.jpg)

![Nicholas Mangan, Ancient Lights

(2015) [detail]. Two-channel HD video installation powered with photovoltaic off-grid system: video #1 HD colour, sound, continuous loop (13 mins 41 secs); video #2 colour, silent, continuous loop (5 mins, 12 secs).](/media/thumbs/uploads/2018_01/010_DSC7328_jpg_380x125_q85.jpg)

![Nicholas Mangan, Ancient Lights

(2015) [detail]. Two-channel HD video installation powered with photovoltaic off-grid system: video #1 HD colour, sound, continuous loop (13 mins 41 secs); video #2 colour, silent, continuous loop (5 mins, 12 secs).](/media/thumbs/uploads/2018_01/011_DSC73551_jpg_380x125_q85.jpg)

![Nicholas Mangan, Limits to Growth

(2016-2017) [detail].

14 TerraHash Antminer bitcoin mining rig (offsite), two single-channel HD colour videos with sound (2mins 29secs and 3mins 5 secs), digital prints, archival image. Collection of the AGNSW.](/media/thumbs/uploads/2018_01/012_DSC7315_jpg_380x125_q85.jpg)

![Nicholas Mangan, Limits to Growth

(2016-2017) [detail].

14 TerraHash Antminer bitcoin mining rig (offsite), two single-channel HD colour videos with sound (2mins 29secs and 3mins 5 secs), digital prints, archival image. Collection of the AGNSW.](/media/thumbs/uploads/2018_01/013_DSC7322_jpg_380x125_q85.jpg)

![Nicholas Mangan, Limits to Growth

(2016-2017) [detail].

14 TerraHash Antminer bitcoin mining rig (offsite), two single-channel HD colour videos with sound (2mins 29secs and 3mins 5 secs), digital prints, archival image. Collection of the AGNSW.](/media/thumbs/uploads/2018_01/014_DSC7311_jpg_380x125_q85.jpg)

![Nicholas Mangan, Limits to Growth

(2016-2017) [detail].

14 TerraHash Antminer bitcoin mining rig (offsite), two single-channel HD colour videos with sound (2mins 29secs and 3mins 5 secs), digital prints, archival image. Collection of the AGNSW.](/media/thumbs/uploads/2018_01/015_DSC7279_jpg_380x125_q85.jpg)

![Nicholas Mangan, Limits to Growth

(2016-2017) [detail].

14 TerraHash Antminer bitcoin mining rig (offsite), two single-channel HD colour videos with sound (2mins 29secs and 3mins 5 secs), digital prints, archival image. Collection of the AGNSW.](/media/thumbs/uploads/2018_01/016_DSC7301_jpg_380x125_q85.jpg)

Advertising in this column

Advertising in this column Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

This Discussion has 0 comments.

Comment

Participate

Register to Participate.

Sign in

Sign in to an existing account.