Warren Feeney – 7 October, 2017

De Lautour remains, first and foremost, a figurative painter. It is evident in the title of the current exhibition and also in the immediate experience of the paintings, particularly the three large works that dominate the space of the Nadene Milne Gallery. De Lautour's painting cannot let go of the material world.

Anyone paying attention to Tony de Lautour’s paintings over the past decade cannot help but notice its apparent evolution from the supposedly “bad attitude” and streetwise art of the 1990s and early 2000s into a more formalist and abstract body of work from around 2007. Minimalist colourful images that claim their heritage with the first generation of European abstract painters: Wassily Kandinsky, Kazimir Malevich and Alexander Rodchenko.

Yet, in making such an observation, it also feels like a half truth. Ostensibly, it may be a description that ticks all the boxes, but there remains this nagging sense that there is something about this analogy that is not quite right. A bit like saying that Lucien Freud was a portrait painter or that Edward Hopper was simply an American regionalist.

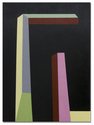

The art historical connections and evidence of geometric abstraction are all there in de Lautour’s paintings but, in a wider context, the works in this current exhibition, Letters of Intent, are not so much about a succession of “avant-garde” motifs or their residue, but the artist’s refined consideration of making images; the editing of his subjects to essential content and his deliberation of space as a subject all of its own, existing within and beyond the surfaces of the picture plane—that is, a conceiving and crafting of painted images that is substantially more than an idea framed within the context of a specific art movement from a particular time and place.

Besides, de Lautour also remains, first and foremost, a figurative painter. It is evident in the title of the current exhibition and also in the immediate experience of the paintings, particularly the three large works that dominate the space of the Nadene Milne Gallery. Yes, there is an important element of abstraction in the geometry and simplification of forms and opened-ended sense of space that they occupy, as well as an absolute care and regard for the positioning of objects and their composition. Yet unlike classically modernist works, there are, for example, few vertical lines running parallel to the edges of the picture plane in these paintings to anchor or curtail their implicit movement and animation.

Paradoxically, although the shapes and constructs in these works may initially appear isolated from each other, they are, in fact, in continuous and animated conversations with one another. And it is a measured and lively visual exchange that has a sure sense of the everyday about it; spirited forms and motifs that could be indicators of letter box signs, golf flags, matches, cotton buds, cigarettes, wooden compasses, night-time street maps, roads signs or streets and buildings.

De Lautour’s painting cannot let go of the material world. Certainly, Letters of Intent has something of its origins in his publication for the Christchurch Art Gallery, Unreal Estate from 2012 with its spray-can geometric shapes masking the promises of a real estate agent’s property guide, and in the process, paying little heed to the notion of property as an idea worth taking too seriously.

So, it should also come as no surprise that Letters of Intent is about conversations. Modern Letters 5, is a painting of animated exchanges, bouncing off one another, shifting directions and attention between objects that are positioned just far enough apart to be able to reach out and touch one another - but not quite. These paintings possess an energy and spirit that invites comparison with Len Lye’s animations or George Herriman’s Krazy Kat comic strips from the 1930s.

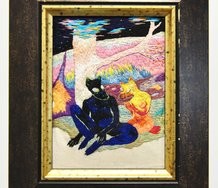

And there is a further series of conversations going on in these works with de Lautour’s practice from the past 25 years, immediately evident in the elongation and verticality of his subjects, sharing much in common with figures like those in State Security, 1997 or Smoking Head from 2004. More importantly, however, it is de Lautour’s “aerial” paintings or “mind-maps” from the 2000s that represent the key precedent for Letters of Intent. Underworld 2, from 2006 in the Christchurch Art Gallery is one of the artist’s largest works, a dense and industrious night-life map, scoping the artist’s practice, and like the paintings in Letters of Intent, unreservedly democratic in its distribution of figures and forms across the surface of the picture plane. His new paintings may not have the frenetic lightning bolts and maze of opportunities and directions that Underworld 2, immediately offers up for consumption, but in their economy of form and space they are more compelling in their possibilities.

There is a measure and restraint to these paintings, an open-endedness to our experience of space, a visual enigma that gives some explanation as to why it seems somewhat deceptive to describe de Lautour’s painting from the past decade as a series of geometric abstractions. There is an unreserved confidence about these works that exists beyond the source material that they may be referencing, verifying that Letters of Intent includes some of the finest paintings of de Lautour’s practice to date.

Warren Feeney

Advertising in this column

Advertising in this column Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

This Discussion has 0 comments.

Comment

Participate

Register to Participate.

Sign in

Sign in to an existing account.