Peter Dornauf – 16 February, 2018

Key is not the first to play the appropriation game and not even with Goya. British artists, the Chapman Brothers, Jake and Dinos, have taken Goya as reference points for their black humoured sculptural and dioramic creations, though with more dark comedy than what Key allows. There are lots of nude bodies in Key's paintings but no tortured or mutilated corpses. The torture here is all mental and emotional.

You may remember Wellington artist, Roger Key, from such paintings as his engaging portrait of Captain Cook (shirt undone revealing a bare chest covered in tats that depict dusky maidens positioned provocatively under coconut trees) or his image of that delicious little number of a debutant—Queen Elizabeth—stripped down to bra and panties.

Key is ever the iconoclast cocking a snook at establishment values, laying bare, literally and otherwise, the foundational myths that help prop up our civilization and its foremost narratives. A little deconstructive spade work is all in a day’s work for this predominantly figurative artist.

But he can also operate the other way round, taking, for example, the old masters and reworking them, or at least their tropes, in a spirit of homage, and recasting them for contemporary ends. This he has done with a new suite of works, 43 figurative paintings, using Goya as his model, in an exhibition currently showing at the Wallace Gallery, Morrinsville.

Goya’s dark brooding, sometimes nightmarish landscapes (complete with tormented figures), become, in Key’s hands, archetypical images to do with universal themes of suffering and conflict that help him construct his own histories. As Goya chronicled his era, politically and morally, so Key attempts the same in more existential terms. His own idiosyncratic ‘disaster’ series examines the small and larger personal anguishes all flesh is heir to; the insanities, trials, tribulations, the struggles and absurdities that bedevil us all on individual and relational levels.

Goya was sometimes described as the first of the moderns because of his direct and unflinching look at humanity. Key also possesses a similar steady, undaunted gaze at human folly and pain.

Key is not the first to play the appropriation game and not even with Goya. British artists, the Chapman Brothers, Jake and Dinos, have taken Goya as reference points for their black humoured sculptural and dioramic creations, though with more dark comedy than what Key allows. There are lots of nude bodies in Key’s paintings but no tortured or mutilated corpses. The torture here is all mental and emotional.

In Endless Conjectures, for example, two nude females are pictured in the throes of some kind of anguish. They are almost melodramatically presented, fists clenched; one is on all fours as if inspecting the ground for answers, the other has arms raised, head bowed against a landscape suggestive of a garden, with small blue flowers sprinkled across the surface of an otherwise empty brown landscape. It is all happening under a heavy brooding Goyaesque sky.

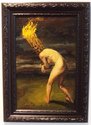

The paint is applied impressionistically, being textural and thick in places as if to mimic the palette of his template. What is immediately apparent are the framing devices the artist has chosen to encase his canvases. They are as theatrical as the paintings themselves, wildly baroque, full of swirls and curls, ornate and over-elaborate as if to either highlight or subvert, or both, the drama unfolding before the viewer in the paintings.

Added to the rich opulence of the frames, all painted in highly polished browns, is a certain kitsch element that exhibits itself by the fact that some of the frames were once lavish decorative dishes or splendid ashtrays. In these the artist has constructed his painterly narratives so that high drama—together with the low and tacky—sets up a frisson where readings can go back and forth along a scale that starts at crisis and ends in farce. Storm in a teacup or drowning at the deep end, these works tease and entertain by turns while the title of the show, Minor Events, adds a little tongue in cheek to the mix.

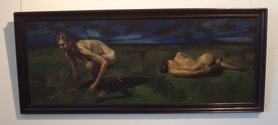

In Scattered Blossoms, two figures, one that crouches while the other lies down on the ground with her back to us, recalls the work of Pierre Puvis de Chavannes, complete with the dark and slightly ominous shadows cast on the earth. The sky might be blue and the grass green, but everything is overlaid with menace. The blossoms that are scattered across the flat landscape might suggest hope, but the characters involved in their pangs and distress seem oblivious.

Ironically in Chiliad, the female nude bent over inspecting the flora, finds instead bones growing up out of the soil. Perhaps this alludes to the “Valley of dry bones” referred to in the book of Ezekiel and the prophecy that the skeletons would come to life. This gets a kind of literal treatment in Deep Light that pictures an old woman stepping up out of the ground as if emerging from a grave.

For the most part life here seems to be consumed by people in combat -two men wrestling, anguished figures bent over searching the ground, women doubled over in pain. The occasional comic element is introduced that sees the heads of figures wearing masks made up of logs of wood. The overall impression one is left with is Sturm und Drang, where the overblown drama is tempered by the cheeky mockery found in the faux framework surrounding the art.

Full marks to the artist for attempting a subject rarely confronted in New Zealand artist circles today.

Peter Dornauf

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects Advertising in this column

Advertising in this column

This Discussion has 0 comments.

Comment

Participate

Register to Participate.

Sign in

Sign in to an existing account.