John Hurrell – 25 February, 2018

'Lost World' the book is a different experience from 'Lost World' the exhibition—in what you can extract from the images. Again very complicated, but deliciously different.

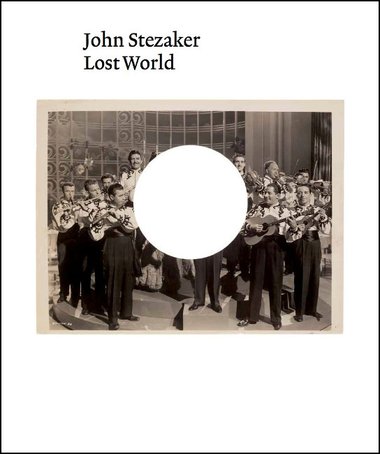

John Stezaker: Lost World

Catalogue for the touring exhibition curated by Robert Leonard for City Gallery.

Essays by Robert Leonard and Geoffrey Batchen

Interview with the artist by David Campany

All touring works illustrated

90 pp, softcover

Ridinghouse, UK, 2017

Accompanying the wonderful touring exhibition of John Stezaker collages—curated by Robert Leonard—that is being presented in Wellington, New Plymouth, Christchurch and Melbourne, this catalogue from Ridinghouse comes illustrating every collage in the show, reproduced with essays by Robert Leonard and Geoffrey Batchen, and an interview with Stezaker by David Campany. Yet for all the commentary, these works have so much life and independence in their subconscious delving, it doesn’t really matter what their creator says—or how eruditely thinkers like Leonard, Batchen, or Campany might comment about them—such thoughts are secondary to the vast range of extraordinary sensations, emotions and ideas these collages generate for the receptive viewer.

More importantly, the documentation in hard copy format allows a new, different kind of viewing of Stezaker’s images—an activity not possible in the gallery situation.

Here are some examples:

With a book you can invert the photographs of the Stezaker collages, something you may wish to do but cannot when viewing the original collages in the gallery. The physicality of the cut and/or juxtaposed (sometimes curling) photographs is removed in the catalogue, but you can flip the image over and see (perhaps) the source material more clearly. This especially applies to my three favourite works: Bubbles (2016), Double Shadow LII (2015), and Double Shadow XLII (2015). (pp73-75). These remain utterly mysterious even though you do gain more information by seeing previously inverted background figures the ‘normal’ way up. Some sections become clearer, others remain baffling.

In the one film presented, Crowd (2013), the rapid sequential projection of multiple images ensures that it is very hard to recognise (and then remember) individual shots, even if they are in an infinite loop. But of course some you do, and each viewer spots different things. However the four provided catalogue images give an impression at odds with the experience of watching in the darkened gallery. They are frozen photographs—vivid in detail—of several projected frames overlapping. The result is nothing like the viewer experience when the sheer flurry of sequencing images (24 frames a second) makes most of the information inaccessible.

If we look at the five mannequin hands that in the exhibition were surrounded by walls of trimmed photographs where hands played a crucially expressive role, in the publication each is photographed in isolation on its plinth. They now look more like Catholic holy relics, especially if you look at the battered fingers and bruised or worn wrists. They also seem to reference the Thousand Armed Bodhisattva Guan Yin (Avolokitesvara) with their multiple expressively refined and delicate gestures.

The main advantage of a book like this is that it is an anthology you can examine over and over, rescrutinising collages that initially you could dismiss, but which you might later within discover something unexpected—like with a book of poems or a CD of music. You might for example concentrate on the edges of the geometric subtraction (large white circles or squares), looking at body parts they touch, or echoing repetitions of the pale form articulated in the surrounding subject matter.

Lost World the book is a different experience from Lost World the exhibition—in what you can extract from the images. Again very complicated, but deliciously different.

John Hurrell

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects Advertising in this column

Advertising in this column

This Discussion has 0 comments.

Comment

Participate

Register to Participate.

Sign in

Sign in to an existing account.