Terrence Handscomb – 11 April, 2018

In 2001 The Homely found intellectual currency in the uncanny, the Gothic and a postcolonial context that suited it. Now, the supplementary cognition of the weird and the eerie seem like remote psychoanalytical estrangements or sci-fi anachronisms. When immediacy and simultaneity are tyrannical demands, then a slow, poetic, contemplative sense of temporality and abstraction is needed and slow film is a timely metaphor.

Gavin Hipkins’ vast career-wide review exhibition The Domain (Dowse Art Museum, 25 November 2017 - 2 April 2018) includes a 3/8 version of Hipkins’ magnum opus The Homely that was first presented in New Zealand in The Homely: an Artist’s Project by Gavin Hipkins in City Gallery Wellington (7 July, 2001-16 September 2001). The Homely was first presented in Flight Patterns (MOCA Los Angles, 2000).

Against the reduced reappearance of The Homely at The Dowse is the current, strategically timed, first presentation of The Homely II, which is included in the exhibition This is New Zealand, again in City Gallery Wellington (3 January - 15 July, 2018).

❖

The Homely (2000) assumes great historical and mythological presence in The Domain, Hipkins’ first major career-wide review of his vast corpus of work. The original Homely is a suite of eighty photographs collected from around Australia and New Zealand. At the time Hipkins likened it to “a post-colonial gothic novel” and NZ curator and co-opted essayist Lara Strongman saw it as “... a popular account of our culture which casts it as irredeemably gothic, [because we are] a people forever menaced by the unforgiving nature of the landscape and the hard-wired tendency to madness in the face of isolation.”

Furthermore The Homely points to a darker psychoanalytical underbelly of Australasian culture, in particular the Freudian principle of the Unheimliche, or the uncanny as it is usually translated into English.

Strongman :“The Homely trains the unheimlich principle on to Australasia’s developing post-colonial identity.” This is a work of profound cultural psychoanalysis, in which Hipkins has pictured the national character.” (1)

This, one supposes, is the unique burden peculiar to a New Zealand post-colonial identity. Yet the character of art history and of finding meaning in texts about art that have become trapped in time, means that Strongman’s sort of thinking has a disinterred narratological presence that will continue to haunt The Homely II.

The Homely II appears towards the end of Hipkins’ career-based transition from the artist whose confident visual intelligence and quirky point-and-shoot acumen that we all came to admire (and more often, to love) in his still images, to moving image that was characterised by what I see as Hipkins’ directorial hesitancy as he grappled with a new medium, new materials and new content. The Domain provides the perfect opportunity to trace this visual migration. But the procedural aspects of learning new visual vocabularies and developing the skilled articulation and procedural fluidity needed for an artist to convincingly speak in a new visual language, is a tough call.

In Hipkins’ film This Fine Island (2012, 12:10) the film’s overarching strength is its postcolonial narrative. But postcolonial narratives are two-a-penny in New Zealand and many New Zealand artists have learned to press all the right cultural buttons. This Fine Island presses many of them. Yet, the film is one of the most honest works in Hipkins’ corpus, and to my thinking, one of the most seminal works in The Domain. I am not talking about its earnest story arcs but of its clumsy procedural honesty and formal cinematic naïveté.

This Fine Island has the cinematic structure we usually see in mainstream and arthouse cinema. Yet Hipkins’ transition away from static image entailed a deeper problematic than that of merely learning new procedures. Films made by artists that co-opt the production values of mainstream cinema usually require learning new skills such as story arc structuring and directing actors, camera people, film editors and so on. These techniques must be mastered when artists make mainstream films.

❖

American painter David Salle’s attempt at making a satirical “Hollywood tale of hustlers, pop philosophy and big money,” turned out to be a hopeless mess (although Salle’s critical writing is wonderful). Salle’s mainstream film Search and Destroy (1995, 1h 30min), which despite its stellar indie cast (Christopher Walken, Rosanna Arquette, Dennis Hopper), received a insulting thirty-three percent Tomatometer score on Rotten Tomatoes, the American review aggregation website for film and television. Variety film critic Emanuel Levy’s was one of the many critics that assigned Salle’s film a scornful splattered green tomato.

Emanuel Levy: “Visual artist David Salle’s eagerly awaited premiere, “Search and Destroy,” aspires to be an inventive black comedy of the absurd with sharp social commentary, but instead is a disappointing film with few bright moments and many more tedious ones. Major talent behind the cameras and a dream cast of eccentric actors only partially overcome the trappings of a misconceived film that is poorly directed.” Variety, 29 January 1995

Although painter Julian Schnabel’s first film Before Night Falls (2000) met with much more enthusiastic critical acceptance, and his later film The Diving Bell and the Butterfly (2007) even more so —and Turner Prize winning video artist Steve McQueen made the hit movie 12 Years a Slave (2013)—the dismal performance of Search and Destroy belies the question: should we judge artists’ films in exactly the same way as we judge filmmakers’ films? Asking this more succinctly: should we judge Hipkins’ films with the expectation that they should affect us in exactly the same way, and to the same extent, that his earlier static image work may have?

The indubitable irony of Hipkins’ best point-and-shoot-omg-he-nailed-it work in The Homely and (in my estimation) much of The Vision (1995) and Bible Studies (2009) for example, is disappointingly absent when we look at the most cringeworthy parts of This Fine Island. I am talking about the scene which should never have been included in the final edit; late in the film where the two actors—with what appear to be Toi Whakaari student-level acting skills—run willy-nilly through an orchard.

If strong directing is missing or it is not determinate, then a film crew will end up doing what they want in ways they like. To a good extent, This Fine Island suffered from that. In my estimation, it was not until New Age (2016) that Hipkins developed the moving image camera skills and the editing proficiency that singled his return to skilful visual storytelling.

One of the most pleasing curatorial strengths of The Domain is that This Fine Island demonstrates curator Courtney Johnston’s willingness to include all of Hipkins’ major works. The Domain is a huge show at The Dowse, the scale of which would have unlikely been allowed at Auckland Art Gallery, if indeed they would have picked it up at this time.

❖

In the meantime, over at City Gallery, Wellington, The Homely II is being presented for the first time in the exhibition This is New Zealand, in the same location as The Homely in 2001.

The textual impulses that ran through The Homely left an intellectual patina that glosses every visual surface. The most evident example is Hipkins’ own reading of a footnote to a 1970’s English-language translation of Sigmund Freud’s historical essay Das Unheimliche (1919). His later reading of British critical-theorist Mark Fisher’s discussion of the weird and the eerie (Mark Fisher, The Weird and the Eerie (London: Repeater Books, 2016), is reiterated (in part) in George Clark’s essay “There is No Motion in Motion Pictures: On Cinema, Photography and the Essay Film” commissioned for The Domain publication (pp 34-45).

However, rather than faithfully follow Hipkins’ extrinsic intellectual leads into his work (the ones he instructively provides)-as George Clark did (albeit spoken with a pompous academic accent)-and as Lara Strongman did in her essay “Gothic Revival,” seventeen years ago (in Gavin Hipkins The Homely, Wellington: City Gallery, Wellington, 2001, pp. 6-11), I prefer to find my own way into The Homely II by exploring, what I see to be, the anti-utopian ‘slow cinema’ pulses of Hipkins’ films Erewhon (2014, 17:24), The Port (2014, 92:34) and New Age.

We live in a world in which the production of new utopias, as well as an “overwhelming increase in all manner of conceivable dystopias,” have become “monotonously alike.”(2) This is how film theory academic Mark Bould began arguing in his discussion of the recent prolificacy of what he calls the “dystopian impulse of slow cinema.” (3) Dystopias (the narratives as well as the places) are dull places, that is, until the point at which they fail. The narrative failure of a dystopia is revolutionary because it overrides our inability to imagine new and better worlds by diminishing our willingness to imagine worse ones:

… what if forty years of neoliberalism’s violently reiterated dogma that “there is no alternative” has left us incapable of imagining not only better worlds but also worse ones? (4)

This is not the dystopia we were promised. (5) We do not live in a world that is ruled by the systems of cruel totalitarian rule as imagined by George Orwell and Aldous Huxley. Cold war anxiety narratives have become dated. The world we live in is one that is attempting to emotionally come to terms with the chicanery of the Cambridge Analytica scandal, the populist Brexit sculduggery, the credibility collapse of Wikileaks and Facebook, and so on. Today, the insidious reach of new surveillance technologies—social media—have greater corporate efficacies than the previous political ones of cold war totalitarian rule; although political bad players today have learned to covertly harness them. Personal privacy and unmediated social choice have effectively disappeared.

These are the widespread social and political milieux against which The Homely II must gain traction. This means that The Homely II must ratify its intellectual legacy in a social and political environment that is not what it was seventeen years ago. In 2001 The Homely found intellectual currency in the uncanny, the Gothic and a postcolonial context that suited it. Now, the supplementary cognition of the weird and the eerie seem like remote psychoanalytical estrangements or sci-fi anachronisms. When immediacy and simultaneity are tyrannical demands, then a slow, poetic, contemplative sense of temporality and abstraction is needed and slow film is a timely metaphor.

Spanish film-maker Mauro Herce’s Dead Slow Ahead (1h. 14min, 5 October 2016), chronicles the trans-Atlantic ocean crossing of the freighter Fair Lady. With its average shot length of forty seconds (as opposed to Hollywood’s average shot length of four to six seconds), the film instantiates Bould’s poignant observation that “slow cinema casts us adrift, and upon our own resources, in the unstable realms of semiosis and affect.” (6)

As I see it, slow film is the cultural metaphor for The Homely II and in slowness the work must find meaning. Hipkins’ has already touched upon cinematic slowness with his ‘feature length’ film Erewhon. Running at just over a whopping ninety-two minutes with long-cut editing, the film is nevertheless remarkably engaging because its aesthetic face points away from the purist complaint that slow film “demand[s] great swathes of our precious time to achieve quite fleeting and slender aesthetic and political effects.” (7) Yet there is something about Erewhon that informs The Homely II.

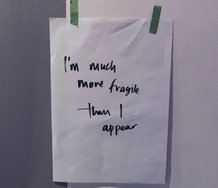

Compared to The Homely, The Homely II is indeed dull. Yet, all of Hipkins’ usual tricks are there: family and friend shots with faces turned away (feelings that deny personality); repressed or hidden sexuality (shots of sperm-like balloons and phallic thermometers); ‘the “obscene jelly” of jouissance’ (8); derelict and depressing anti-utopian architecture; psychoanalytical egresses between this world and another—it’s all present. But the cognitive pace of the work is different. It is dull and it is slow; it is a twenty-first century dulltopia. Fabulous! (9)

It is an error to read The Homely II as either a mere reiteration of The Homely or as a cynical attempt to resurrect its past glories. If the critical consensus of The Homely II goes down that road, then the work is unlikely to be seen as anything more than a not-so-good-as-the-first recital that is tolerated because its predecessor generated so much love, and people are unwilling to abandon good feelings. However, if The Homely II is seen as a child of its time (despite the age of some of the shots), and it represents the depressing cultural dullness in which upbeat cultural narratives are possessed only by the rich-and reality television and populist social media are the cultural currencies for the rest of us-and if a slower, quieter secular religiosity is to be found in The Homely II, then all will be good. That is, until the repressed melancholy that lies deep in this work speaks of things we would rather not hear, and we simply turn away.

Terrence Handscomb

1. Lara Strongman, “Gothic Revival,” in Gavin Hipkins: The Homely (Wellington: City Gallery, Wellington, 2001), p 8.

Note that the German language text of Freud’s 1919 discussion of the uncanny is titled Das Unheimliche, usually translated in English as The Uncanny. The first psychoanalytic use of the term seems to be due to Ernst Jentsch (1867-1919) in Zur Psychologie des Unheimlichen (On the Psychology of the Uncanny), 1906.

In German, substantive nouns are always capitalised, whereas their adjectival forms are not. However, the English language use of the uncapitalised, but the italicised unhemlich (adjective) preceded by the English definite article is a widespread linguistic error. Although the definite article in this instance refers to the noun ‘principle”, this means that “unheimlich” takes an adjectival form but one that has not been declined to match the case and gender of the noun, that is das unheimliche Prinzip.

2. Fredric Jameson, An American Utopia, ed Slavoj Žižek, London: Verso Books (2016); quoted in Mark Bould, “Dulltopia: On the Dystopian Impulse of Slow Cinema”, Boston Review, 22 January 2018

3. Mark Bould, ibid.

4. Ibid.

5. Henry Farrell, “Philip K. Dick and the Fake Humans,” Boston Review, 16 January, 2018.

6. Mark Bould, op. cit.

7. Nick James’ editorial discussion of slow cinema in Sight and Sound (April 2010), quoted in Bould op. cit.

8. Mark Fisher, The Weird and the Eerie, London: Repeater Books, 2016, p.17.

9. The expression “dulltopia” is due to Mark Bould, op. cit.

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects Advertising in this column

Advertising in this column

This Discussion has 0 comments.

Comment

Participate

Register to Participate.

Sign in

Sign in to an existing account.