John Hurrell – 20 August, 2018

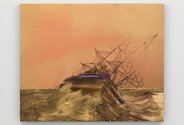

The image of a tipped-over clipper in turbulent circumstances is a metaphor that Bedford is often partial to, but in the past it has referred to her own volatile emotional state and her romantic relationships. In this new show she has changed the meaning of the nautical trope so that it refers no longer to herself but is much broader—referring to the perilous state of our planet.

Los Angeles artist Whitney Bedford has been showing her ink and oil paintings every couple of years, regularly at Starkwhite since 2010. This is her fourth show, and as usual there is a lot of maritime subject matter, and images of densely overgrown desert vegetation. Most of all she is known for images of old fashioned sailing ships that usually are at the mercy of howling gales and ferocious waves.

Bedford likes to blend delicate illustrative ink drawing with the gestural sweeping use of oil paint and the occasional cloud of finely splattered dots. She is very good at making these imposing displays. This one includes a couple of drawn on metallic coloured panels, featuring sprayed shiny gold surfaces, or wooden panels covered directly with oil paint, or with linen underneath. The works are all on wooden panels that are unframed, with lots of monochromatic sky. Consequently they look lean and elegant.

Most of the intricately rendered ships have parts covered over by swirling single-lined brush marks, spiralling in vortexes around the boats—but not penetrating the works’ picture plane. The swirling lines of paint cling to the panel surface, while also wrapping themselves around—or tumbling over—the ships. They mingle gestural abstraction with perspective-based illustration, jamming and locking the two spatially opposed templates together.

The image of a tipped-over clipper in turbulent circumstances is a metaphor that Bedford is often partial to, but in the past it has referred to her own volatile emotional state and her romantic relationships. In this new show she has changed the meaning of the nautical trope so that it refers no longer to herself but is much broader—referring to the perilous state of our planet. This apprehension about earth’s future is not only because of obvious ecological deteriorations, but also the various global rivalries that refuse to acknowledge them.

For an artist to take an oft repeated metaphorical image, and then alter its stipulated meaning, is a risky project. It undercuts the interpretative value of both past and current work. Yet there have been some changes in the battered clipper motif itself. The tilted hull—with its horizontal stripes-looks slightly mineral-based and stratified, with links to geological formations. A reference to the earth’s rocky substance perhaps.

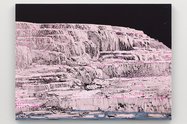

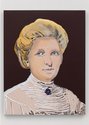

The title of Bedford’s show, Bohemia, denotes a calming place of refuge (a “fantasy arcadia”) where ships can go to escape in these reactionary, chaotic and confrontational times. Included amongst the nine works are three that reference New Zealand. Two feature the Pink and White Terraces destroyed in the Tawawera eruption, and the other is a portrait of pioneer feminist, Kate Sheppard.

These images focus on the collective power of scattered marks to render landscape and the human face. The Pink and White Terraces painting (2018) and study (2018) work well expressively in terms of abstract design, though the long vertical lines tend to compress spatially and turn the foreshortened flat terraces into much steeper cliffs. The Kate Sheppard portrait (2018) unlike them is quite painterly, and despite clusters of dots positioned around the side of her head to introduce volume the image remains flat.

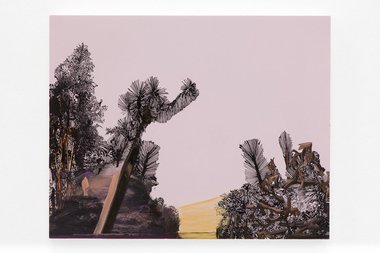

Bedford’s drawing skills are more easily appreciated in Hot Wind/ Moving Fast (2015), a rocky, treecovered outcrop, and The Hideaway (2015) an image of a cove where spiky-leaved trees and bedraggled shrubs are growing over short banks that encase the mouth of a stream. With the latter, as with the ship paintings, dragged thin paint is a crucial element, here presenting vertical and diagonal muddy sweeps that plummet to the sea. Angular leaves and dappled textures activate the skyline. If you saw this scene (say) while out whitebaiting—waistdeep in water—you probably wouldn’t even notice, but here, depicted by Bedford with its integrated modernist flourishes, it becomes magic.

John Hurrell

Advertising in this column

Advertising in this column Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

This Discussion has 0 comments.

Comment

Participate

Register to Participate.

Sign in

Sign in to an existing account.