John Hurrell – 21 September, 2018

There are some nice coincidental ideational interconnections amongst the four contributions, such as both Tyrell and Buchanan emphasising group values over individualistic, or Fraser and Johnson/Ward surrounding the visitor's body with non-directional sound and vertical light-emitting forms. While I think only half of the work is successful, as an eccentric group show it is certainly stimulating—through its unforeseen juxtapositions.

Auckland

Ruth Buchanan, Jacqueline Fraser, Jess Johnson & Simon Ward, Pati Solomona Tyrell

The Walters Prize 2018

Selected by Lara Strongman, Stephen Cleland, Megan Tamati-Quennell, Allan Smith

18 August 2018 - 20 January 2019

This year, in the ninth Walters Prize, there is a split between the artists who revel in moving image (Johnson and Ward, Tyrell) and those that don’t (Fraser, Buchanan), a division between those who use movement to hook the audience, and those who prefer them to ‘read’ static images or texts.

Note I use the word revel. All four artists have moving image components somewhere: Buchanan has flickering strobelike texts that rapidly change in an optically abrasive manner; Fraser has a film projected onto a plane of streamers that is hard to decipher; Johnson and Ward have five plasma screens where Johnson’s delicately coloured drawings are digitally animated; and Tyrell’s main project is a very lively filmed presentation of dance, recital and theatre.

It is a show where the floor space is disastrously divided, where spatially there is none of the cohesion of say 2012 when Kate Newby won and the four finalists were elegantly lined up in a row, nor any of the adventurous performance ‘radicality’ of 2014 when Luke Willis Thompson got it and some of the finalists were outside the gallery.

All the 2018 finalist works are complicated and ambitious, one being extremely convoluted because it references three other parts of the gallery outside The Walters Prize exhibition. In fact, all the finalists are compromised by it: Fraser is marginalised by her position on the outer edge of the other three, where she could be easily missed; Tyrell’s photographs are squeezed awkwardly into a narrow corridor outside his film; Buchanan’s normally sprawling project is tightly crammed into a confining space like sheep in stockyards; and Johnson and Ward’s work looks too small compared to the others, a modest ramp with freestanding monitors, surrounded by a sea of darkness.

Overall this is probably the worst looking of the nine Walters Prize exhibitions so far—for these spatial reasons—but note the design and subdivision might be the host institution’s fault, not the individual artists or the selection jury. What the judge-Adriano Pedrosa-will make of it is anybody’s guess.

The best Ruth Buchanan shows I’ve seen (at Hopkinson Mossman, AUT or Govett-Brewster) demonstrate her interest in a Flaubert story about him arranging the furniture in a room as if it were the syntactical parts of a sentence through using objects like curtains, screens, and seats (as say, parenthesis, colons and phrases), but this AAG presentation is so cluttered nothing is given a chance to function clearly as symbol. Possible viewer analysis is hampered by the mazelike structure that is devised (with language and mirror) to make the viewer aware of their own body moving through the institution, although the two German artists she introduces to her audience in her text and the ‘off site’ locations (Marianne Wex, with her body language/gender photo documentation, and Judith Hopf, with her snake sculptures) are indisputably fascinating. Perhaps more, in fact, than Buchanan herself—in this ‘maximalist’presentation anyway.

Pati Solomona Tyrell‘s photographic portraits of himself, family and various FAFSWAG friends seem to be in a hotel foyer, an uncomfortably claustrophobic hang—and mix of styles, some of which owe a lot to Lisa Reihana’s Digital Marae. Like Buchanan’s work these portraits, dense with symbolic body ornament, need space. The film in the adjacent room however is wonderfully vibrant, with its overlapping spikily dressed human bodies, staunchly fluid sexualities, Pasifika ethos, community advocacy and penetrating sound. It is compellingly theatrical, a crowd pleaser, but not shallow. Rich in sexual and racial politics—and beautifully structured in its articulated components—there is a strong sense of emotional substance.

Jacqueline Fraser‘s selected hip hop sound track supports her well known, large collages (that often feature repeated body images) and square-roomed tinsel ‘club’ installation, by regularly disrupting (through dance tracks from artists like Kendrick Lamar, Eminem or Michael Jackson) the soundtrack of the projected film In the Heat of the Night, the great 1966 film made by Norman Jewison, featuring Sydney Poitier and Rod Steiger. The overlapping pieces of black fabric, sheets of sequins and ripped pages from male fashion, gardening or black culture magazines, are clearly more about rhetoric than aesthetic, ‘in your face’ attitude more than articulated argument. Fraser’s shimmering walls of streamers are theoretically disrupted by the three big collages, in parallel to the film soundtrack interventions by her music choices. One set of relationships is reflected by the other, light and sound together.

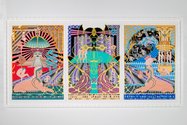

With Jess Johnson and Simon Ward, Ward gives movement and plasticity to Johnson’s circus poster, sci-fi and mutant-mask drawings. The installation, a keyhole shaped ramp surrounded by darkness, with its five vertical video screens seems to blend kabbalistic sefirot and occult symbols to make a critique of the World Wide Web. It’s like a pinball arcade on a circular spotlit platform in a darkened fairground tent. Ward’s animation is similar to Auckland artist Gregory Bennett’s but infused obviously with Johnson’s pastel /carnival sensibility and decorative, deep chequerboard space—with a lot more contrasting stasis that retains Johnson’s poster sensibility. The work overall seems small compared to its competitors, though it is engrossing with its many complex cosmologies and bizarre elements like production-line androids masturbating each other. It is not totally immersive like Tyrell’s presentation—but more distanced in its contemplative, psychedelic, Haight-Ashbury design attributes.

There are some nice coincidental ideational interconnections amongst the four contributions, such as both Tyrell and Buchanan emphasising group values over individualistic ones, or Fraser and Johnson/Ward surrounding the visitor’s body with non-directional sound and vertical light-emitting forms. While I think only about half of the work is successful, as an eccentric group show it is certainly stimulating—through its unforeseen juxtapositions.

John Hurrell

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects Advertising in this column

Advertising in this column

This Discussion has 0 comments.

Comment

Participate

Register to Participate.

Sign in

Sign in to an existing account.