John Hurrell – 15 February, 2019

Like with, at times, Martin Creed in the UK, or Sean Landers in the States—and in Aotearoa: Tom Kreisler, Peter Robinson, Tony de Latour and Ronnie van Hout—anxieties are rubbed raw like a sore, accentuated and exposed as a source of grim (self-mockingly masochistic) entertainment, sometimes like smiling lips wrapped around clenched teeth. Excavating neuroses lurking deep within the Self. Funny in a way that is more rueful than perky.

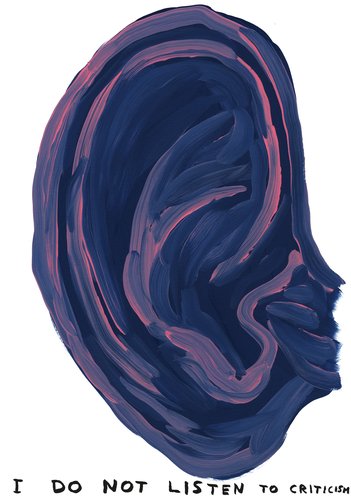

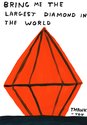

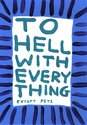

No canvases this time, these new works from English artist David Shrigley are all on paper, framed and under glass. One short wall is devoted to a grid arrangement of 30 works using black ink drawing/cartoons on paper, featuring his characteristic airy linear style. The other long walls show rows of coloured acrylic works—50 in total—featuring densely blocked out shapes and recognisable silhouettes with paint that is straight out of the tube, unmixed. All these ostensibly ‘clumsily crafted’ artworks have at least a little text somewhere. All involve humour.

Shrigley is known for his prodigious (very recognisable) output. He is ubiquitous—his books, buttons, tote bags, pillow-slips, tee shirts, gallery art, public commissions etc are everywhere—world-wide. He cleverly combines successful marketing with entertaining quips that have immediacy—within the work’s ‘raw’ anti-artisan (anti-fiddly), droll sad-sack style. They are usually not profound in any way-to claim that would be pompous—though they focus on the everyday, the comfortably prosaic. They are just bloody funny. He is not trying to be a philosopher, though they could (it might be argued) be a form of therapy.

However the most obvious challenge for an internatuional star like Shrigley is to make drawings and paintings that viewers and purchasers won’t tire of, and want more. One liners that keep on thrilling—that maintain the intensity of the reader’s chuckle—that draw them back through formal manual properties that continue to entertain. Most certainly do.

Part of their appeal lies in an ugliness or gawkiness—in the tradition of James Thurber, B. Kliban, John Lennon and Ronald Searle, but much looser, scratchier and spindlier—that gives you the giggles. The laughter generated by the presence of the written-on captions (not titles) makes them beautiful; they acquire an anti-aesthetic aesthetic. What is normally awkward (if not repulsive) becomes reluctantly cute and even easily digestible.

Shrigley’s considerable cartooning skill (however you define that) and extraordinary energy in producing so much, seems effortless. He has a touch that knows instinctively how to communicate with audiences that often are scared of art, especially art that requires prolonged reading. He avoids the dryly academic (is never esoteric), yet can communicate with university boffins too. His detractors (in public forums anyway) are almost non-existent. His carefully cultivated, misery-guts, persona is irresistible.

Some of these works have punchlines via a second, more snide, sentence; while in others a single short bitter phrase is enough. Like with, at times, Martin Creed in the UK, or Sean Landers in the States—and in Aotearoa: Tom Kreisler, Peter Robinson, Tony de Latour and Ronnie van Hout—anxieties are rubbed raw like a sore, accentuated and exposed as a source of grim (self-mockingly masochistic) entertainment, sometimes like smiling lips wrapped around clenched teeth. Excavating neuroses lurking deep within the Self. Funny in a way that is more rueful than perky.

John Hurrell

Advertising in this column

Advertising in this column Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

This Discussion has 0 comments.

Comment

Participate

Register to Participate.

Sign in

Sign in to an existing account.