Peter Dornauf – 13 August, 2019

An overview of the show reveals a wide and eclectic range of works, from the traditional through to the experimental. The plural is in the ascendency, which is a healthy sign. Interestingly the largest category, fifteen in total, were works that played with abstraction in various guises. In terms of subject though, the political predominates, which is no surprise, given that this is New Zealand.

Hamilton

Group show

National Contemporary Art Award

Curated by Fiona Pardington

3 August-10 November 2019

National art awards can be seen as an opportunity to take the pulse of the nation, at least the pulse that beats in time with the avant-garde in this country. However, various caveats need first be applied, given that the sample is often small, in this case around 300 hopefuls, whittled down to 50. And also, with an awareness that in this case again, the largest contingent ended up coming from Auckland and Wellington.

Then there’s the factor of a single judge, each of whom come with their own peccadillos and preferences. The judge this year was artist, Fiona Pardington, a first for this award when an artist has been invited to cast judgement on their peers.

An overview of the show reveals a wide and eclectic range of works, from the traditional through to the experimental. The plural is in the ascendency, which is a healthy sign. Interestingly the largest category, fifteen in total, were works that played with abstraction in various guises.

In terms of subject though, the political predominates, which is no surprise, given that this is New Zealand. It reflects a contemporary compulsion to feel relevant in a world heavily politicised through mass and social media, and where in this country, politics is often the only game in town.

The winner on the night, and recipient of $25,000, was someone no one anticipated, which is always gratifying in a perverse sort of way. Auckland artist, Ayesha Green, with her faux folk art rendition of Nana’s Birthday (A Big Breath), took the top award.

All the abstractionists, the conceptualist and minimalists were trumped by this humble, non-political, folksy and slightly sentimental conventional painting complete with frame. All of which is sort of pleasing given that it went against the grain, and a brave call by the judge.

The painting presents a simple and ‘banal’ scenario. However looking a little closer, other things are also seen to be going on, not least of which is the racial mix denoted by the different tones of colour painted on the cartoon-like faces of the subjects. And formally, the composition is a judicious arrangement of triangles and circles. Unsophisticated, naïve, yet sophisticated.

The artist draws attention to the inevitable trajectory of time, birth to death, but also the sense of timelessness that comes with generations stretching back behind any one individual.

Sagaciously placed nearby is a video work by Kirsten Smith which acts as the perfect foil to the accord displayed in the “Nana” painting. Art Project is one of the best art videos I have seen in a long while, a kind of animated version of Green’s work, but with agitation and conflict at its core. It is beautifully rendered, using all the visual tricks employed by commercial media. Particularly engaging is the use of Fauve/Pop Art colouration and apt exploitation of truncated body forms. This is a sharp, snappy one-minute drama complete with arty soundtrack. Clashing mother and daughter never looked so deliciously aesthetic.

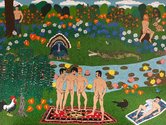

The ‘folk art’ treatment continues with the work of Laura Williams who is making a name for herself with her lush paradise scenes done out in a kind of Rousseauian trope. Into these innocent settings she places her figures, mostly male and mostly nude, in order to upset traditional art conventions, in this case the ubiquitous female nude presented for the male gaze.

Slightly engorged genitalia are freely on display—fig leaves are verboten—as these young bucks hang out together on an exotic Turkish rug against the backdrop of a flower strewn river and festoon hills. Williams is having enormous fun here as she lines up her manly protagonists in this perfumed Elysian field, sardonically entitled Meadow Larks.

Next door, on the same wall, Kate Leslie presents her painted utopian dream world, a blue lagoon garlanded with South Pacific tropical palms, reminiscent of Gauguin and rendered in loose brush strokes. In an All Blue World is a landscape, devoid of people, but possessed of the same verdant lushness captured by Williams.

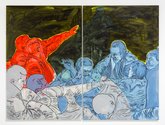

Is this the dream that people want? Artist Gerry Parke thinks he knows. His mural size painting, What People Really Want, depicts a jumble of male figures in what appears to be the throes of protest and political affirmation. Two prominent men in red gesture heroically, arms outstretched, recalling the Tennis Court Oath by David which depicted one of the seminal events associated with the French Revolution.

However, close examination of the dark background reveals the disturbing presence of skulls, barely visible, an unsettling reminder of the terrible cost that comes with radical social and political change. Such idealistic political movements of the twentieth century linked to the same raised arm salute remind us that what people want and what they get often collide with terrible consequences.

The minimalist aesthetic employed in the painting—charcoal and spray paint—provide a street art look which effectively marries style and content.

Engagement with the vernacular is something artist Geoff Clarke embraces, as seen in his abstract wall relief sculpture. Hybridity is his preoccupation and Double Slit exemplifies that with its fusion of abstraction, Op Art, decorative design and reference to recent architectural forms employing venetian blinds on building facades. Such democracy of forms is his way of blurring aesthetic boundaries where street culture meets high art.

Clarke also has a problem with abstraction and the question of meaning. Historically, twentieth century abstractionists loaded their works with some kind of grand redemptive metaphysic. Post-modern’s have deflated the heroic bubble, but the “redundancy of meaning” is something Clarke takes issue with.

Looking at Merit Award winner, Matt Browne’s work, Anecdoche, it would seem there is no meaning afoot, other than formal considerations, a delight in colour and shape, the push and pull of space. Yet, ironically, he claims the painting is “open to multiple meanings”, bog standard practice among the art cognoscenti.

At the other end of the scale is Gina Matchitt’s He Tohutono, (runner up to the winner), sporting a flag within a flag format. Here, singular meaning is spelt out in spades. Art becomes propaganda at this point, strident and megaphone loud.

A quieter improvisatory tactic, though vigorous in execution, is used by Mandy Roger, doing imitations of Judy Millar where brushstroke is fêted: first explored by Roy Lichtenstein taking the piss out of the abstract expressionists.

But most quiet is Totem #1, an abstract by Gene Paul Walker. One of the buzz words in the world of art speak is “process” and Walker claims it, but if one gets past that, then the diminutive triptych, a small subtle ‘sculptural’ painting, delights with its subdued reference to Joan Miro.

The above art works are just a sample from the show to demonstrate that the art beat of Aotearoa pulsates with a plethora of rhythms, and that the reverberations of folk art are a pleasing addition-mixed into the clamour of sound emitting from the more esoteric end of contemporary art in New Zealand.

Peter Dornauf

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects Advertising in this column

Advertising in this column

This Discussion has 0 comments.

Comment

Participate

Register to Participate.

Sign in

Sign in to an existing account.